160 Acute Pulmonary Complications in Pregnancy

Pulmonary Physiology in Pregnancy

Pulmonary Physiology in Pregnancy

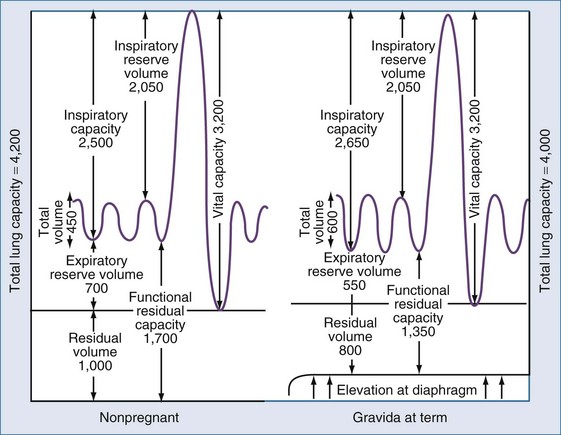

A number of physiologic changes affect respiration during pregnancy. Normal pregnancy is associated with a 20% increase in oxygen consumption and a 15% increase in metabolic rate. During the first trimester, minute ventilation is increased while respiratory rate remains the same. Although one might assume that lung volume during pregnancy would decrease owing to the rise in the maternal diaphragm, tidal volume (VT) is actually increased by 40% over baseline values. The increase in VT is thought to be due to the increase in circulating progesterone that affects the respiratory center.1 Arterial blood gas measurements reflect a respiratory alkalosis that is compensated by a metabolic acidosis that results in a relatively normal pH. PaCO2 usually ranges from 28 to 32 mm Hg. Functional residual capacity (FRC), residual volume, and total lung volume are decreased near term. Because of this decrease, respiratory distress occurs more rapidly in the gravid than in the nongravid state. The function of the large airways as measured by forced expiratory volume at 1 second (FEV1), and peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) is essentially unchanged throughout pregnancy.2

Figure 160-1 illustrates the graphic relationship of pulmonary changes.

Asthma

Asthma

Epidemiology

Asthma is one of the most common pulmonary problems in pregnant women; recent studies report that approximately 8% are affected.3 The disease is characterized by hyperactive airways leading to episodic bronchoconstriction. The role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of asthma has become apparent in recent years, leading to earlier use of inflammatory medications in the treatment of exacerbations.

Effects of Asthma on Pregnancy

Asthma may be triggered by environmental allergens, medications, especially aspirin or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or stress.4 Most exacerbations are marked by cough, wheezing, and dyspnea. Rapid therapeutic intervention at the time of an exacerbation is imperative to prevent impaired maternal and fetal oxygenation, because uncontrolled asthma can increase maternal morbidity. In several studies, even after controlling for confounding variables, adverse pregnancy outcomes are more pronounced in patients with asthma. These include low birth weight, preeclampsia, preterm birth, and stillbirth.5,6

Whereas historical data have shown an increase in perinatal death and low birth weight,7 Fitzsimmons and colleagues observed low birth weight in only those patients treated for status asthmaticus.8 In addition, Schatz and colleagues noted that intrauterine growth restriction was directly related to lung function as measured by FEV1.9

Effect of Pregnancy on Asthma

Numerous studies have observed that the course of asthma may be affected by pregnancy. Gluck et al. found that on average, asthma improved in 36% of women during pregnancy, remained unchanged in 41%, and worsened in 23%.10 Schatz et al., in an analysis of 366 pregnancies in which patient status was followed by objective criteria, found that asthma improved in 28%, remained unchanged in 33%, and worsened in 35%. Fifty-nine percent of the patients had similar asthma control in successive pregnancies.11

Fetal sex may influence asthma in pregnancy. In one study, mothers who gave birth to boys were more likely to report improved asthma symptoms.12 Dodds and colleagues also found that the use of medications to treat asthma was less common in mothers of boys.13 While a number of hypotheses have been proposed, including alterations in progesterone and the role of leukotrienes, changes in not one of these mediators can explain the varied course of the pregnant asthmatic.14

Management

The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEP) issued specific guidelines regarding asthma treatment. In 1993, the Working Group on Asthma and Pregnancy established criteria for diagnosis and treatment in the gravid population (Figure 160-2).15

Pharmacologic therapy is the mainstay of asthma treatment. Most drugs used in the treatment of asthma are thought to be safe in pregnancy. Inhaled β-agonists are the most frequently used in asthma treatment. A prospective study of inhaled β-agonists in 259 pregnancies showed no change in the rate of congenital malformation, perinatal mortality, low birth weight, or complications of pregnancy.16 There is little role for the use of oral β-agonists, which may have more adverse systemic symptoms and are no more effective than inhaled drugs.

Inhaled corticosteroid therapy remains the mainstay of antiinflammatory treatment of asthma. Corticosteroids have also been advocated as first-line therapy in patients with mild asthma.17 Studies have demonstrated that with asthma, those taking an inhaled corticosteroid were four times less likely than their nontreated counterparts to suffer an exacerbation.18 Another randomized study noted that there was a 55% reduction in readmission rates for acute asthma in patients using inhaled beclomethasone.19 Inhaled corticosteroids can increase the effectiveness of β-adrenergic agents by inducing the formation of new β receptors. Because beclomethasone is the most studied of the inhaled corticosteroids in pregnancy, it is recommended as first-line therapy.15 However, if patients are well controlled on other corticosteroid preparations, it is suggested they be continued on their current medication, because all inhaled corticosteroids are labeled by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as pregnancy class C. Other antiinflammatory medications used in the treatment of asthma (e.g., cromolyn sodium and nedocromil sodium) appear to be less effective than inhaled corticosteroids in reducing asthma symptoms.

Intravenous corticosteroids have no increased benefits over oral corticosteroids in the treatment of acute exacerbations.20 Methylprednisolone, hydrocortisone, and prednisone are safe for use in pregnancy, unlike betamethasone or dexamethasone, because very little active drug crosses the placenta.

Leukotriene pathway moderators have been shown to improve pulmonary function, as measured by FEV1.21 Zafirlukast and montelukast are rated FDA category B; however, there is little experience with these drugs in pregnancy, and their role is undetermined.

The treatment of asthma requires patient education to provide optimization in the preconceptional period and during the pregnancy to provide optimum outcome. Box 160-1 offers a suggested schematic for the treatment of asthma in pregnancy.

Box 160-1

Treatment of Asthma in Pregnancy

Moderate Asthma

Status Asthmaticus

Status asthmaticus is a rare complication in pregnancy. Diagnosis is established by a PaO2 of less than 70 mm Hg, a PaCO2 of greater than or equal to 35 mm Hg, or a measured expiratory flow of less than 25% of expected. Because of impending respiratory failure, these patients should be managed in a critical care unit. Aggressive treatment of status asthmaticus is mandatory to protect the mother and fetus. Maternal mortality may be as high as 7% and fetal mortality as high as 11% despite adequate treatment. Epinephrine is not contraindicated in pregnancy during a respiratory emergency. Criteria for intubation in the gravida with status asthmaticus include (1) inability to maintain PaO2 of greater than 60 mm Hg despite supplemental oxygen; (2) inability to maintain a PCO2 of less than 40 mm Hg; (3) evidence of maternal exhaustion, with worsening acidosis (pH < 7.2) despite intensive bronchodilator therapy; and (4) altered maternal consciousness.15

When traditional treatment proves to be ineffective, a number of therapies have been reported beneficial. The use of a helium-oxygen mixture that has been reported to be effective in nonpregnant studies has been used safely in pregnancy.22

Pulmonary Edema

Pulmonary Edema

Etiology

Other causes of acute pulmonary edema in pregnancy include amniotic fluid embolism, aspiration, and the need for massive transfusion after hemorrhage.23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree