Acute Eye Infections

Tricia C. Loo

Eye infections are encountered in the ED in a broad spectrum ranging from minor to severe. The majority of infections seen in the ED are minor, but it is very important that the emergency physician learn to recognize the signs and symptoms of severe infections which, if missed, could lead to compromise of vision and be devastating to the patient. This chapter addresses a variety of eye infections, including conjunctivitis, keratitis, keratoconjunctivitis, endophthalmitis, and orbital and periorbital cellulitis (see Chapter 255).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Conjunctivitis refers to inflammation of the mucous membranes that line the eyelids and sclera. Causes of conjunctivitis include viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic (rare) infections, allergic, chemical exposure, and contact lens wear. The main bacterial pathogens include Haemophilus Influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae species in both children and adults, and Moraxella catarrhalis in children. The most common cause of viral conjunctivitis is adenovirus. Contact lens wearers are at risk for gram negative infections, including Pseudomonas. Most patients presenting to the ED with conjunctivitis have a self-limited condition, but the emergency physician must be wary of patients presenting with serious etiologies (i.e., bacterial or herpetic conjunctivitis) that could result in vision loss if left untreated.

Patients with bacterial conjunctivitis may present with symptoms of eye redness, mucopurulent discharge, and itching. Patients with viral conjunctivitis present with bilateral watery discharge and foreign body sensation. Upper respiratory infection typically precedes viral conjunctivitis. Discharge from either cause can result in crusting and sticking of the eyelids, which is especially notable after sleep. The quality of discharge or associated findings such as an enlarged ipsilateral preauricular lymph node, are commonly used to differentiate between viral and bacterial conjunctivitis, but there appears to be little evidence of these associations or of any specific factors aiding this differentiation (1).

Keratitis refers to inflammation of the cornea. Infectious keratitis frequently involves the conjunctiva as well and is referred to as keratoconjunctivitis. This condition usually causes significant pain for the patient and may have viral or bacterial etiologies as well. Patients with keratitis usually present with intense eye pain, tearing, redness, and sometimes photosensitivity. Herpes keratitis may produce severe pain and a corneal dendritic lesion.

Blepharitis refers to inflammation of the eyelids and is one of the causes of a persistent red eye. Chronic inflammation can lead to the meibomian glands getting clogged. If the glands get infected, a painful lump forms, and this is known as a hordeolum/sty. A chalazion is not truly an infection but a chronic inflammatory process leading to granuloma formation surrounding blocked sebaceous or meibomian glands.

Blepharitis may result in red, swollen eyelids, a foreign body sensation, tearing, crusting of the eyelid margins, eye pain, or photophobia. With hordeolum, similar symptoms are often present, but typically a focal area of erythema and swelling of the eyelid is noticed. Similarly, a chalazion usually causes a focal area of inflammation that is usually subacute in onset and most times occurs proximal to the eyelid margin.

Endophthalmitis is inflammation of the intraocular structures (vitreous and/or aqueous humor). It most frequently results from exogenous causes (i.e., ocular surgery or penetrating trauma), but can also rarely occur from endogenous causes (i.e., bacteremic seeding of the eye). Patients with endophthalmitis often exhibit more significant clinical findings, including eye pain, vision loss, headache, discharge, and photophobia. Acute endophthalmitis is a medical emergency and requires aggressive antibiotic therapy (both systemic and intravitreal) and urgent ophthalmology consultation.

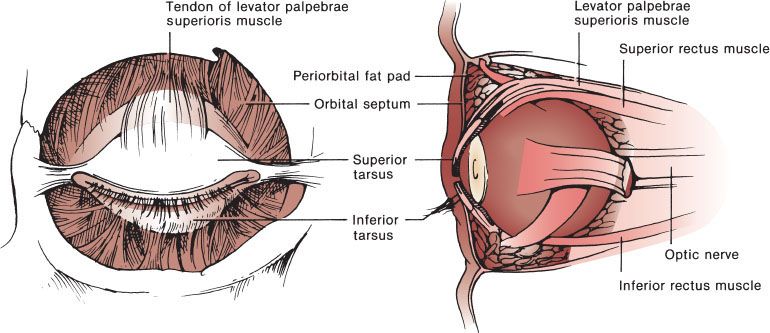

Preseptal and orbital cellulitis are relatively uncommon and affect children more frequently than adults. Preseptal cellulitis refers to infections of the soft tissues anterior to the orbital septum (Fig. 60.1). Orbital cellulitis refers to infections posterior to the septum (fat and ocular muscles). Preseptal cellulitis is more common than orbital cellulitis, and most frequently arises from external sources (trauma, bites, foreign bodies). Orbital cellulitis most frequently arises from rhinosinusitis. Periorbital cellulitis typically involves erythema, edema, and warmth of the periorbital tissues and also may involve closure of the palpebral fissures. Fever may be present. There should be no complaints of ocular pain, pain with movement of the globe, nor any limitation of globe mobility, all of which suggest the more serious diagnosis of orbital cellulitis.

FIGURE 60.1 View of orbit–orbital septum.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of the red or painful eye is broad (Chapter 56). Infection is a relatively common cause of these symptoms, but a variety of other causes must be considered, including allergic reactions, irritant causes, foreign body, chemical or thermal burns, trauma, medication reactions, orbital disease related to other medical problems (e.g., thyroid disorders), glaucoma, uveitis, mucocutaneous syndromes (e.g., Kawasaki disease, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, etc.), and cancer (2). The differential diagnosis of periorbital cellulitis includes orbital cellulitis, insect bite, allergic response, and hordeolum. The differential for orbital cellulitis includes cavernous sinus thrombosis, endophthalmitis, and tumor.

ED EVALUATION

A thorough but focused history and a careful ocular examination are the keys to ED management of the painful or red eye. The relevant physical examination is described in more detail in Chapters 54 and 56. History should include documentation of previous visual problems or surgeries, current vision complaints, use of glasses or contact lenses, use of general or ophthalmic medications, other general medical problems, trauma, contact with other people who may have ocular infections, contact with or exposure to chemicals or toxins, symptoms of systemic illness (e.g., fever, tachycardia, etc.), history of immunocompromised state from medical conditions or medications, and the pattern of development of symptoms (one eye, both eyes, etc.). Visual acuity should always be documented, as visual acuity is the “vital sign” of the eye. This examination should take place before use of any ophthalmologic medications (e.g., topical anesthetics, mydriatics, etc.). Focused examination of the eye and periorbital areas should then be performed.

Lids

Examination of the eyelids is important to evaluate for crusting or other signs of infectious or dermatologic conditions. Any general or focal erythema or swelling of the lids should be noted. Eversion of the lids and inspection of the fornices for foreign body should also be performed.

Conjunctiva

Examination should identify chemosis or discharge. Membranes may be present in infections involving adenovirus but may be due to S. pneumoniae, diphtheria, or rarely, herpetic disease. Conjunctival hemorrhage may be present and is often petechial when caused by adenovirus. Copious discharge may be present in gonococcal conjunctivitis. Hemorrhage may also be secondary to other organisms such as S. pneumoniae. Follicular reaction, creating a “cobblestone” appearance in the lower palpebral conjunctiva, is typically seen with adenovirus infection but may be secondary to allergic or toxic causes (3).

Cornea

The cornea should be specifically examined for signs of ulceration. Most ulcers are centrally located, and fluorescein staining may reveal spots or specks of increased uptake over areas of corneal epithelial damage. Larger areas of corneal epithelial injury signify ulceration and require ophthalmologic consultation for further management because the possible complications include corneal scarring and vision loss. Fluorescein staining may also reveal the typical dendritic pattern associated with herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) may also cause corneal ulcers. Care must be taken to examine the nose for involvement with the typical zoster lesions. Herpetic eruptions involving the nose may signify that the nasociliary branch of the ophthalmic nerve is involved. Corneal involvement is likely in this scenario and is referred to as the Hutchinson’s sign. Corneal ulcers associated with blue or greenish discharge are often associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Urgent (next-day) ophthalmology referral is often adequate for small corneal ulcerations, but larger or more extensive ulcerations require ophthalmologic consultation in the ED. Fungal ulcers are often caused by Candida, Aspergillus, or Fusarium species. The incidence of fungal infections is increasing secondary to the increasing number of patients with AIDS and because of the increasing use of immunosuppressive medications. Contact lens use also predisposes to corneal ulceration.

Anterior Chamber

Slit-lamp examination for evaluation of the anterior chamber is important to evaluate for signs of iritis (uveitis). White blood cells (“cell and flare”) visualized in the anterior chamber are the key finding with iritis. Iritis may be related to significant corneal surface infections or ulcerations. A hypopyon, the layering of the white blood cells in the anterior chamber, may be seen and represents a true ocular emergency. Presence of a hypopyon requires immediate ophthalmology consultation.

Periorbital Areas and Skin

Erythema and swelling in the periorbital area may be secondary to local inflammatory causes or infection, but underlying preseptal or orbital cellulitis should be considered. There are a number of key points to remember when performing the physical examination of this area:

• Preseptal cellulitis may present with sufficient swelling to affect visual acuity and ocular motility.

• Fever is absent in as many as 24% of all patients with preseptal and orbital infections.

• Unilateral involvement is the rule rather than the exception for both preseptal and orbital cellulitis.

• Examination should be performed with the assumption that the patient has orbital cellulitis until proven otherwise.

• Proptosis and painful eye movements or extraocular movement impairment are more often associated with orbital cellulitis, although subperiosteal or orbital abscesses may cause similar findings (4).

The bacterial pathogens in orbital and preseptal cellulitis are typically the same organisms causing the predisposing condition: sinusitis, upper respiratory infection, local skin infection, dental infections, or postsurgical infections. Most commonly, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. pneumoniae, or other streptococcal species are causative agents, but many others have been implicated. H. influenzae type b vaccine has dramatically decreased this organism’s role as a pathogen in children with preseptal or orbital cellulitis (5). Staphylococcus sp are now seen most commonly in children with these infections. The prevalence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) continues to increase with rapidly growing numbers of ophthalmologic-related S. aureus isolates being reported as methicillin-resistant (6).

When preseptal or orbital cellulitis is considered, further diagnostic testing may be indicated. For the systemically ill patient, particularly pediatric patients, blood cultures may be useful. With orbital cellulitis, blood cultures are negative in two-thirds of children and 90% to 95% of adults (3). Cultures of eyelid aspirates and eye secretions are rarely helpful and are not recommended, unless there is a clear source of cutaneous infection. Cultures of cerebrospinal fluid are recommended only for infants in whom meningeal signs are evident.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning of the orbit is the preferred method of imaging for orbital infections. CT scanning of the orbit is advocated in all children in whom orbital cellulitis cannot be clearly ruled out by examination (7). Many authors recommend obtaining axial and coronal CT views to improve diagnostic yield in regard to subperiosteal or orbital abscesses that may be missed if only axial views are obtained (8–10). There is no advantage to using contrast-enhanced versus noncontrast CT scans. Orbital or subperiosteal abscesses are identified on CT scans in only 80% of cases (11), and diagnosis of orbital infection remains primarily a clinical one. Ultrasound has been used in some centers for diagnosis, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be a useful alternative for patients requiring surgical treatment.

KEY TESTING

• CT of the orbits, if orbital cellulitis is suspected