55 Acute Coronary Syndrome

• Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) occurs as a spectrum of diseases that includes unstable angina pectoris, non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

• ACS is classically manifested as chest tightness or pressure with associated dyspnea, nausea, and diaphoresis.

• ACS is diagnosed through a careful history and analysis of the 12-lead electrocardiogram.

• Treatment of the spectrum of ACS involves oxygen, aspirin, beta-blockers, nitrates, and anticoagulants.

• Patients with evidence of myocardial infarction also benefit from clopidogrel and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors.

• Patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction require early revascularization therapy with either fibrinolysis or primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

• Immediate complications of ACS include congestive heart failure, cardiogenic shock, and rhythm disturbances, both tachyarrhythmias and bradyarrhythmias.

Epidemiology

Nonetheless, the burden of ACS remains significant both from a health care perspective and from an economic perspective. More than 1 million acute MIs occur in the United States annually, and 20% of affected patients die before reaching the hospital, primarily from arrhythmias during the first hours of symptoms.1 Many survivors of acute MI are left with impaired cardiac function, which adversely affects their ability to perform activities of daily living and their quality of life. Approximately 6 million emergency department (ED) visits in the United States are made annually for the evaluation of chest pain, and as many as one in three of these patients are ultimately found to have ACS.2 The annual cost of providing care for patients with ACS, both immediately and then later for those who survive, is more than $100 billion.3 Finally, despite advances in diagnostic techniques, 2% to 5% of patients with acute MI are discharged from the ED because their disease is not identified.4 These “missed MI” patients represent the highest mean payments for emergency medicine–related medical malpractice claims.

Definitions

Myocardial infarction is defined as myocardial necrosis. Clinical criteria for the presence of an acute, evolving, or recent MI, which have been laid out jointly by the American College of Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology, focus on any evidence of myocardial cell death. The exact definition of an acute or evolving MI is a rise above the upper limit of normal and subsequent fall in levels of cardiac biomarkers specific for myocardial necrosis (troponin or the MB fraction of creatine kinase MB [CK-MB]) along with at least one of the following5:

• Symptoms consistent with ACS

• ECG evidence of myocardial ischemia, specifically, ST-segment elevation or depression or T-wave inversions

• Development of pathologic Q waves on the ECG

Myocardial infarction is further classified as STEMI and non–ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI). STEMI is present when the patient has (1) cardiac biomarkers for necrosis as previously defined and (2) new or presumed new ST-segment elevation in two or more contiguous ECG leads. The cutoff point for ST-segment elevation is 0.1 mV.6 Contiguous leads are defined in the chest leads as V1 through V6 and in the frontal plane as the sequence aVL, I, inverted aVR, II, aVF, and III. Patients who meet the clinical criteria for STEMI and left bundle branch block (LBBB) and are not old or who have ECG evidence of an isolated true posterior MI are also considered, for treatment algorithm purposes, to have STEMI. NSTEMI is present when the patient meets the criteria for MI as previously defined but exhibits no evidence of ST-segment elevation, new LBBB, or ECG evidence of an isolated posterior wall MI.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis in patients with ACS includes a host of other diseases that can be manifested as chest pain or dyspnea: stable angina, pericarditis, myocarditis, pulmonary embolism (PE), aortic dissection, pneumonia, pleurisy, pneumothorax, Boerhaave syndrome, esophageal reflux, esophageal spasm, gastritis, biliary colic, pancreatitis, peptic ulcer disease, musculoskeletal pain, and herpes zoster. One of the historical features that tends to favor a diagnosis of ACS is chest pressure or tightness rather than a sharp pain, which is more commonly associated with pericarditis, pleurisy, pneumothorax, PE, and aortic dissection. In addition, the chest discomfort in patients with ACS tends to gradually worsen, unlike the pain associated with PE or aortic dissection, which is generally worst at the onset and then persistently severe. Pain of a pleuritic nature tends to favor PE, pleurisy, or pneumothorax, whereas pain that is worse on palpation tends to suggest a chest wall musculoskeletal cause. Discomfort that is positional in nature tends to favor pericarditis or gastrointestinal causes rather than ACS. However, it is very important to remember that a significant percentage of patients with ACS have pleuritic, positional, or palpable chest pain and that these historical features cannot be used to exclude the diagnosis.7

Diagnostic Testing

Electrocardiogram

Electrocardiographic Findings in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

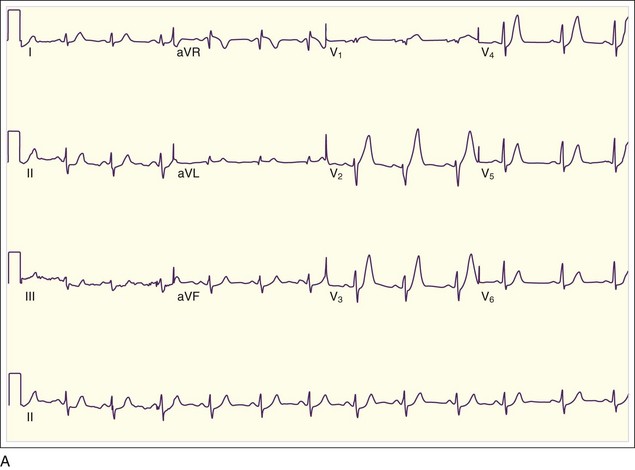

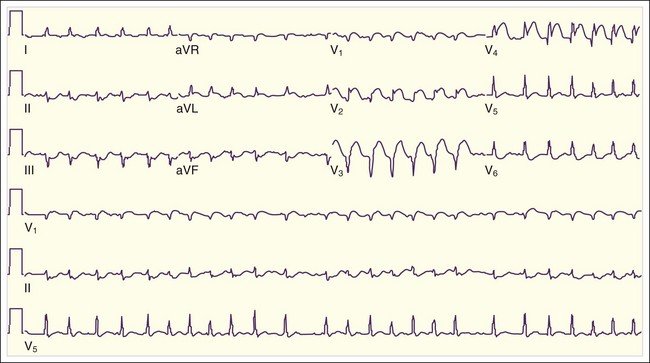

The initial ECG abnormality that occurs in patients with epicardial coronary artery occlusion is peaked hyperacute T waves in the distribution supplied by the IRA. T waves become tall and sharply peaked within minutes of occlusion of the IRA (Fig. 55.1, A). Peaked T waves may also be seen in patients with hyperkalemia, pericarditis, early repolarization, and LBBB. In the next several minutes, ST-segment elevation becomes evident on the ECG (see Fig. 55.1, B). To be diagnostic, the ST-segment elevation must be at least 1 mm above the baseline; this is generally considered the TP segment. Most typically, this ST elevation is convex or domed, though less commonly it may be straight or, rarely, concave. Concave ST-segment elevations are more characteristic of other conditions associated with ST-segment elevation (Box 55.1).

Box 55.1 Differential Diagnosis of ST-Segment Elevation on Electrocardiography

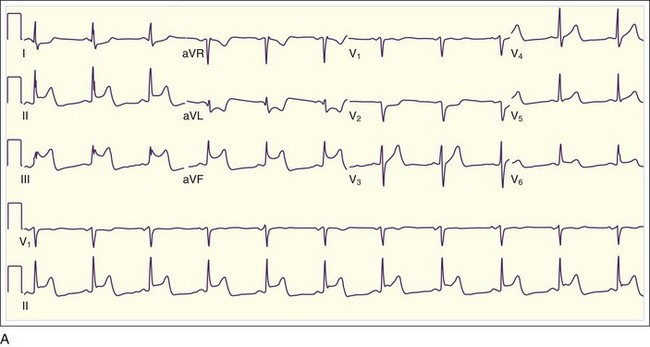

In addition to the clinical situation, a factor distinguishing STEMI from other conditions is the dynamic nature of the ST-segment changes with STEMI; serial ECGs commonly show waxing and waning ST-segment elevation. Hours to days later, the ST segments return toward baseline, the T waves invert, and pathologic Q waves develop in areas of the ECG that correspond to the IRA. The location of the ST elevations and other findings on the ECG generally correspond to the anatomic location of the myocardium and the associated IRA. Anterior infarctions exhibit ST elevation in leads V1 through V4 (Fig. 55.2). Findings in leads V1 and V2 indicate involvement of the septum. MIs with these findings are caused by occlusion of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. When additional ST elevations are seen in leads V5, V6, I, and aVL, the location of the LAD occlusion is probably proximal to the first diagonal branch, which causes an anterolateral infarction (see Fig. 55.1, B). Inferior infarctions are characterized by ST elevations in leads II, III, and aVF (Fig. 55.3, A) and are due most commonly to right coronary artery (RCA) occlusion. Reciprocal ST depressions may be present in leads I and aVL.

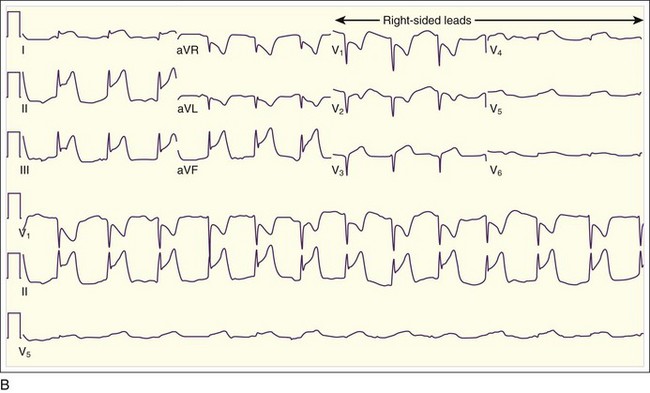

Inferior MIs are associated with concomitant right ventricular infarction, which can be evident on right-sided ECG leads, particularly in RV4 and RV5 (see Fig. 55.3, B). Inferior MIs are also frequently associated with posterior wall involvement, which is seen on the ECG as ST depressions in leads V1 through V3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree