Fig. 12.1

Blunt abdominal trauma workup. (Used with permission from van der Vlies CH, Olthof DC, Gaakeer M, Ponsen KJ, van Delden OM, Goslings JC. Changing patterns in diagnostic strategies and the treatment of blunt injury to solid abdominal organs. Int J Emerg Med 2011 Jul 27;4:47-1380-4-47)

Management

Successful nonoperative management of intra-abdominal injuries is predicated on the stability of the patient. Unstable patients or patients with diffuse peritonitis after blunt abdominal trauma require a laparotomy. Expectant management should only be attempted in a clinical setting capable of intensive monitoring, serial clinical examinations and where an operating room is available for urgent laparotomy at all times.

Liver

In the early 1900s, blunt hepatic injuries were treated primarily by observation alone. Due to poor outcomes, the pendulum then swung the complete opposite direction and laparotomy became the treatment of choice. For hemodynamically stable patients, several options exist for management [5].

The widespread use of CT scans for trauma patients has allowed for the development of a grading scale for solid organ injuries. Liver injuries range from mild (Grade I) to severely life-threatening (Grade VI) (Fig. 12.2a–c). Table 12.1 shows a representation of the AAST liver injury grading system.

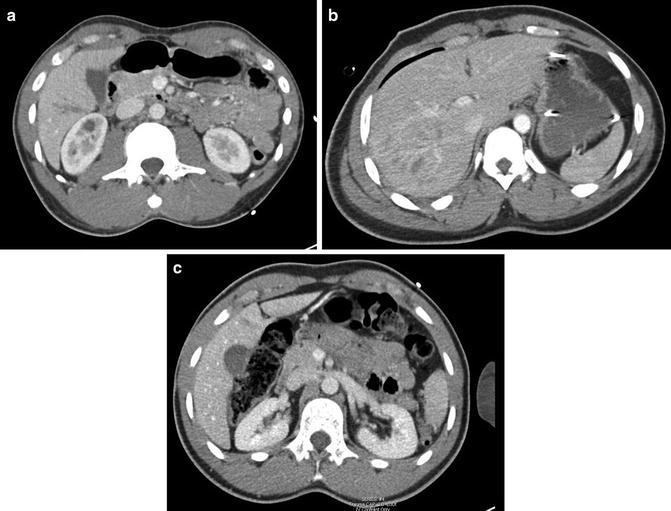

Fig. 12.2

(a–c) CT scan images of liver injuries following blunt trauma. (a) Grade II liver laceration. (b) Grade IV liver laceration. (c) Grade I liver laceration

Table 12.1

AAST hepatic injury grading scale

Grade | Injury type | Description |

|---|---|---|

I | Hematoma | Subcapsular, <10 % surface area |

I | Laceration | <1 cm parenchymal depth |

II | Hematoma | Subcapsular, 10–50 % surface area |

Intraparenchymal, <10 cm diameter | ||

II | Laceration | 1-3 cm parenchymal depth, and <10 cm in length |

III | Hematoma | Subcapsular, >50 % surface area or explanding/ruptured |

Intraparenchymal, >10 cm | ||

III | Laceration | >3 cm parenchymal depth |

IV | Laceration | Parenchymal disruption, 25–75 % of hepatic lobe |

V | Laceration | Parenchymal disruption, >75 % of hepatic lobe |

V | Vascular | Juxtavenous hepatic injuries (e.g., Major hepatic veins, retrocaval IVC) |

VI | Vascular | Hepatic avulsion |

In addition to allowing the injury to be graded, the newer multichannel detector CT scanners allow for more accurate visualization of vascular structures and active bleeding in the form of a “blush” (contrast extravasation). While certain CT findings, such as high grade injuries, active extravasation, periportal blood and large amount of hemoperitoneum, have previously been thought to preclude nonoperative management, recent literature suggests that these risk factors are not absolute contraindications to a trial of expectant management in a hemodynamically stable patient [6]. That said, more severe injuries and patients at with active bleeding are at high risk for needing intervention, and should be considered for early angiography with embolization.

While angioembolization of high-risk patients who suffer liver trauma is highly successful at controlling bleeding, it is not without its own morbidity. Contrast-induced nephropathy is a concern, especially since the vast majority of these patients have already undergone a CT scan with IV dye for diagnostic purposes. Embolization can lead to hepatic necrosis with the delayed complications of infection and abscess formation. Additionally, embolization only addresses vascular extravasation and cannot target bile ducts. Biliary leaks are especially prevalent in higher grade injuries, and can cause ongoing systemic inflammation, bilomas or biliary peritonitis. Most of these patients can be treated without the need for laparotomy with percutaneous drainage and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) [7].

Spleen

Attempting splenic salvage after blunt trauma has become the norm in modern day trauma practice. While unstable patients still belong in the operating room, stable patients and transient responders have options for treatment that include expectant management and angiography with embolization. A CT scan with IV contrast should be performed in this patient population to define the severity of injury and guide the management [8] (Fig. 12.3). Much like with liver trauma, injuries to the spleen are graded based on severity. Table 12.2 shows the AAST grading scale for splenic injuries.

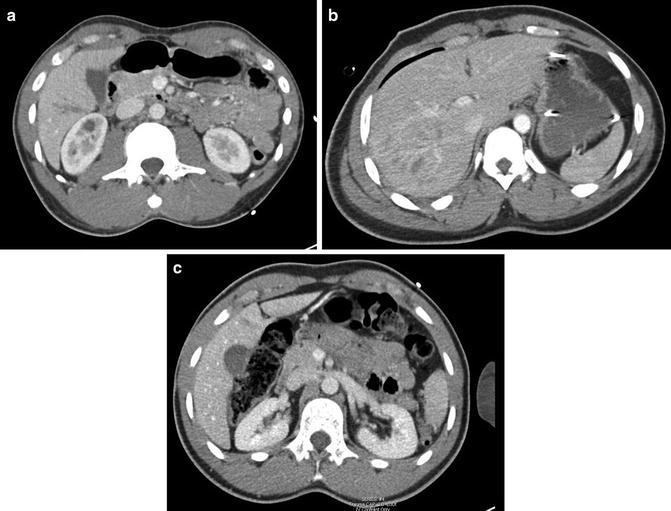

Fig. 12.3

CT scan image of grade III splenic laceration following blunt trauma to the abdomen

Table 12.2

AAST splenic injury grading scale

Grade | Injury type | Description |

|---|---|---|

I | Hematoma | Subcapsular, <10 % surface area |

I | Laceration | <1 cm parenchymal depth |

II | Hematoma | Subcapsular, 10–50 % surface area |

Intraparenchymal, <5 cm diameter | ||

II | Laceration | 1–3 cm parenchymal depth that does not involve a trabecular vessel |

III | Hematoma | Subcapsular, >50 % surface area or expanding/ruptured |

Intraparenchymal, >5 cm or expanding | ||

III | Laceration | >3 cm parenchymal depth or involving trabecular vessels |

IV | Laceration | Involves segmental or hilar vessels producing major devascularization (>25 % of spleen) |

V | Laceration | Shattered spleen |

V | Vascular | Hilar vascular injury with devascularized spleen |

Common sense would dictate that patients with increased hemoperitoneum, higher grade injuries and active extravasation seen on CT would lead to higher failure rates of nonoperative management, and multiple studies proved this to be true [8]. However, there are no absolute contraindications to attempting splenic salvage based on age, severity of injury or presence of concomitant injuries as long as the infrastructure exists for appropriate monitoring [8]. The failure of nonoperative management can be significantly decreased by reevaluating patients with blunt splenic injury 48 h after their trauma with a repeat CT scan to look for pseudoaneurysms [9].

When embolization initially became popular, the main splenic artery was the most frequent target (Fig. 12.4a, b). As technology has improved, selective and superselective embolizations have become possible. One of the main reasons to attempt splenic salvage is to avoid overwhelming postsplenectomy sepsis (OPSI). There was concern that with main artery embolization, the immune function of the spleen would be compromised and patients could suffer the same fate as with splenectomy, hence the trend towards more selective targets. These fears have not been realized; small studies have shown that not only is immune function preserved in patients with main artery embolization [10] but there is no difference in complication rates between main artery and selective embolization [11].

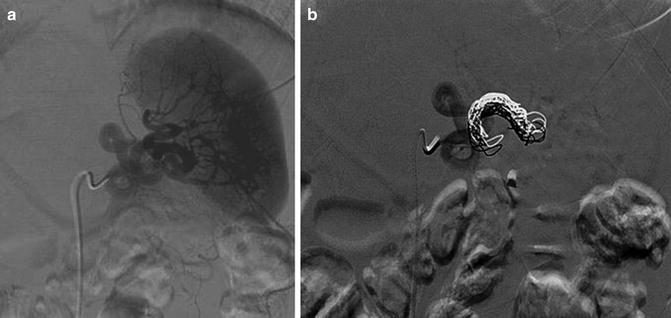

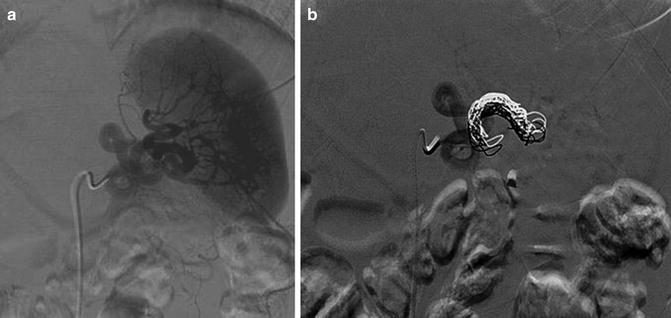

Fig. 12.4

(a, b) Angiographic management of a grade III splenic injury following blunt abdominal trauma. (a) Conventional angiography demonstrating injury and intra-parenchymal splenic blush. (b) Post-coil embolization of the main splenic artery

Kidney

Historically, many blunt renal injuries were explored in the operating room with a resultant high nephrectomy rate. To attempt to increase the kidney salvage rate, nonoperative management of renal injuries became common. The proof that nonoperative management could be successfully carried out came in the form of retrospective studies showing spontaneous healing of injured kidneys on CT imaging [12]. As with the other blunt solid organ injuries, age, severity of injury and presence of head trauma do not exclude nonoperative management as a treatment option. The AAST recognizes five grades of injury for the kidney, as seen in Table 12.3.

Table 12.3

AAST renal injury grading scale

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree