Abdominal Pain and Masses in Pregnancy | 7 |

Adnexal masses complicate between 1 in 81 and 1 in 8,000 pregnancies (Leiserowitz, 2006; Whitecar, Turner, & Higby, 1999). Of these, less than 1% to 13% are malignant (Leiserowitz, 2006; Mukhopadhyay, Shinde, & Naik, 2016; Whitecar et al., 1999). Most adnexal masses in pregnancy are found incidentally on routine obstetric ultrasound (US) as they typically do not cause symptoms, and physical examination is limited by the gravid uterus (Leiserowitz, 2006). Pregnant women presenting with abdominal pain to an emergency department or obstetric triage setting frequently have a diagnostic US to assess the fetus, placenta, and adnexae.

The majority (50%–70%) of adnexal masses in pregnancy resolve spontaneously (Hoover & Jenkins, 2011; Webb, Sakhel, Chauhan, & Abuhamad, 2015). Those that persist into the second trimester pose the greatest concern, as they can be malignant, rupture, torse, or obstruct labor (Hoover & Jenkins, 2011). The actual risk of these complications, however, has been reported as less than 2% (Webb et al., 2015; Whitecar et al., 1999). In the symptomatic woman, one must determine if the adnexal mass necessitates urgent surgical intervention versus observation and pain management.

PRESENTING SYMPTOMATOLOGY

In the first trimester, symptomatic adnexal masses typically present with unilateral or bilateral pelvic cramping or pressure. Larger masses persisting into the second trimester tend to cause unilateral pelvic pain. Midline abdominal pain can occur if the gravid uterus displaces the mass. Severe pain may be associated with nausea and vomiting from peritoneal irritation. In rare cases, a ruptured mass can cause significant internal hemorrhage such that the woman reports dizziness in addition to pain. Uterine irritability or contractions may be seen in the late second and third trimester. In pregnant women with pain secondary to an adnexal mass, vaginal bleeding, rupture of membranes, or impact on fetal status are exceedingly rare. However, symptoms may reflect other underlying obstetric conditions with the incidental finding of an adnexal mass.

HISTORY AND DATA COLLECTION

Obtaining a history in a pregnant woman with abdominal pain is similar to doing so for the nonpregnant patient. Important factors to ascertain are time of onset and duration of pain, inciting or mitigating factors, quality, severity, location, and 68radiation. Associated symptoms can include fever, nausea/vomiting, urinary symptoms, bowel changes, vaginal bleeding, leaking amniotic fluid, contractions, or flank pain. If nausea and/or vomiting are present, long-standing symptoms may represent nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, whereas an acute onset could be associated with the current clinical presentation. Accurate determination of gestational age is critical. Does the woman have a known intrauterine gestation or must ectopic pregnancy be excluded? Obtain the remaining history such as obstetrical, medical, surgical, and social history as per routine. Recent ultrasounds need to be reviewed to help determine how long a mass has been present.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Physiologic changes in pregnancy can affect vital signs. For example, mild tachycardia may be normal in the third trimester but would be atypical in early gestation. Likewise, blood pressure reaches its nadir in the second trimester. Tachycardia and hypotension can also result from significant internal hemorrhage.

In addition to routine cardiopulmonary examination, abdominal examination, and assessment for costovertebral angle tenderness, a sterile speculum and vaginal examination are performed to evaluate for adnexal or uterine tenderness, cervical dilation, and potential rupture of membranes. It is important to ensure an empty bladder prior to abdominal exam to optimize palpation of the adnexa. Also, include an evaluation for presence of lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion, and ascites, as well as a breast examination, should be performed if malignancy is suspected (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2016). Further examination is performed as directed by history.

At 6 weeks gestation, the uterus is similar in size to the nonpregnant state and the adnexa may be palpable in a nonobese patient. The uterine fundus is at the level of the pubis symphysis by 12 weeks and at the umbilicus at 20 weeks. Therefore, clinical examination of the adnexa is extremely limited after 12 weeks gestation.

LABORATORY AND IMAGING STUDIES

If a mass is suspected, US is the preferred imaging modality as it allows for optimal characterization of the mass and determination of its malignant potential (Hoover & Jenkins, 2011; Whitecar et al., 1999). Several studies have shown that antenatal US correctly diagnosed all the malignant tumors in these series (Hoover & Jenkins, 2011; Schmeler et al., 2005; Whitecar et al., 1999). US can be used to examine the kidneys and to assess free fluid in the pelvic cul-de-sac, abdominal ascites in Morison’s pouch, and hemoperitoneum. US has the additional benefit of being cheaper and faster to obtain in most circumstances compared to other modalities.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be employed if additional imaging is needed and is especially useful to delineate the extent and nature of masses that are too large to visualize completely on US or for surgical planning. An MRI should also be considered if appendicitis or other gastrointestinal causes such as inflammatory bowel disease and diverticulitis are suspected (Naqvi & Kaimal, 2015). As with US, MRI avoids maternal and fetal exposure to radiation.

Nonobstetric causes of abdominal pain are best evaluated by computed tomography (CT), as it provides higher resolution imaging of the gastrointestinal tract. Although CT is generally considered relatively safe in pregnancy, it should only be performed when absolutely necessary, as it does expose the mother and 69fetus to 2 to 4 rads per abdominopelvic study (Hoover & Jenkins, 2011). With regard to the use of iodinated contrast media for CT and gadolinium for MRI, both the American College of Radiology and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) note the limited data on safety in pregnancy and advise limiting use to when benefits greatly outweigh risks (Jaffe, Miller, & Merkle, 2007).

Laboratory testing includes a complete blood count to assess for leukocytosis and/or anemia, as these may be present in the setting of torsion or ruptured ovarian cyst. Urinalysis may help exclude urinary tract causes of pain.

Serum tumor markers are of limited utility in the initial assessment of pregnant women as cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) levels are normally elevated in pregnancy with a peak in the first trimester (range, 7–251 units/mL) followed by a steady decrease. Other serum tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) are likewise significantly affected by pregnancy (Hoover & Jenkins, 2011). Tumor markers are largely used to follow disease progression and control in women in whom a malignancy has already been diagnosed (ACOG, 2007; Hoover & Jenkins, 2011).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In addition to the adnexal mass as the source of abdominal pain, the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in pregnant women must include other obstetric and nonobstetric causes of pain. Common sources of pain, unrelated to adnexal masses, include physiologic abdominal pain of early pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, round ligament pain, appendicitis, gastroenteritis, nephrolithiasis, urinary tract infections, and pyelonephritis. Ectopic pregnancy must be included in the differential diagnosis in women with unlocated pregnancies.

Functional cysts such as corpus luteum are among the most common adnexal masses in pregnancy (Hoover & Jenkins, 2011). Other benign masses include mature cystic teratoma, serous or mucinous cystadenoma, endometrioma, paraovarian cysts, and leiomyoma. Malignant tumors are rare. Of these, the most common types are germ cell, stromal, or epithelial tumors of low malignant potential (ACOG, 2007). See Table 7.1 for incidence of common adnexal masses.

Table 7.1 Incidence of Common Adnexal Masses in Pregnancy

TYPE OF MASS | PERCENTAGE (%) |

Mature cystic teratoma | 25 |

Corpus luteum and functional cysts | 17 |

Serous cystadenoma | 14 |

Mucinous cystadenoma | 11 |

Endometrioma | 8 |

Carcinoma | 2.8 |

Low malignant potential tumor | 3 |

Leiomyoma | 2 |

Paraovarian cysts | <5 |

Pelvic kidney | <0.1 |

Sources: Cinman, Okeke, and Smith (2007); Hoover and Jenkins (2011).

70CLINICAL MANAGEMENT AND FOLLOW-UP

The fundamental question in the acute management of pregnant women with adnexal masses is whether to observe or intervene surgically (and when to do so emergently). Factors to consider include the following: degree of suspicion for malignancy, hemodynamic stability, concern for torsion, and pain severity. Most hemodynamically stable women presenting to an emergency department without evidence of torsion may be observed acutely and then managed on an outpatient basis. This allows time to obtain additional imaging or subspecialist consultation, as needed. Abdominopelvic pain may be treated with acetaminophen or oral narcotics in the interim.

Given the inherent risks of surgery, there is a growing body of evidence to support observation and delay of surgery until the postpartum period. The vast majority of adnexal masses noted in pregnancy spontaneously resolve, thus obviating the need for surgical intervention (Hoover & Jenkins, 2011; Schmeler et al., 2005; Whitecar et al., 1999).

Surgery may increase the risk of spontaneous abortion, preterm labor, and rupture of membranes. However, observation can increase risk of torsion, rupture of the mass, peritonitis, hemorrhage, delay in diagnosis of cancer, and obstruction of delivery. Compared with pregnant women not undergoing surgery, the overall risk of premature delivery increased by 22% in those who had surgery, regardless of the surgical approach (Hoover & Jenkins, 2011).

There is conflicting evidence as to whether emergent versus scheduled surgery carries an increased risk of fetal adverse effects. Whitecar et al. (1999) reviewed 130 cases of pregnant women with adnexal masses that required laparotomy. Of these, 16 were emergent. They found that laparotomy at less than 23 weeks gestational age was associated with significantly fewer adverse pregnancy outcomes than at greater than 23 weeks, but there were no significant differences in maternal morbidity or fetal outcomes between emergent and scheduled laparotomy. A later study of 89 women with adnexal masses in pregnancy similarly showed no statically significant difference in adverse pregnancy outcomes following elective versus emergent surgery (Lee, Hur, Shin, Kim & Kim, 2004). A large systematic review of 12,542 procedures in 54 papers assessing pregnancy outcomes after emergent versus elective surgery for non-obstetric indications (e.g., appendicitis, adnexal mass, cholecystitis) concluded that current anesthetic and surgical techniques do not significantly increase the risk of spontaneous abortion, major birth defects, or maternal mortality (Cohen-Kerem, Railton, Oren, Lishner, & Koren, 2005). Reliable assessments of preterm birth and fetal loss rates are difficult to ascertain in this review and others as adverse fetal outcomes in emergent surgery are more likely to be related to the underlying condition that necessitated surgery (e.g., appendicitis) rather than the surgery itself (Cohen-Kerem, et al., 2005; Hoover & Jenkins, 2011). An ACOG Committee Opinion on nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy recommends performing urgent surgery at any gestational age but to delay nonurgent surgery until the second trimester or, preferably, until after delivery (ACOG, 2011).

A study by Schmeler et al. (2005) reviewed 127,177 deliveries and identified 59 women (0.05%) with an adnexal mass 5 cm or greater. Median gestational age at diagnosis was 12 weeks and 80% were diagnosed on US; the rest were identified at the time of the cesarean section. Seventeen women (29%) underwent surgery. Of these, the majority were planned laparotomies for suspected malignancy with the emergent surgeries being performed for torsion. One woman in the surgical group had preterm premature rupture of membranes at 23 weeks with subsequent delivery at 28 weeks. No other adverse fetal outcomes were reported. Forty-two women in the observation group were observed expectantly in the antenatal period and then had surgery either intrapartum 71or postpartum. The median gestational age at delivery for all women was 39 weeks. There was no statistically significant difference in obstetric outcomes between the surgical and observation groups. All the malignant masses had concerning sonographic findings that prompted antenatal surgery. The authors concluded that the risk of malignancy is less than 1% in pregnant women with incidentally identified masses with low-risk features on US, which is similar to rates in nonpregnant women. As such, expectant management may be a reasonable option in appropriately selected women.

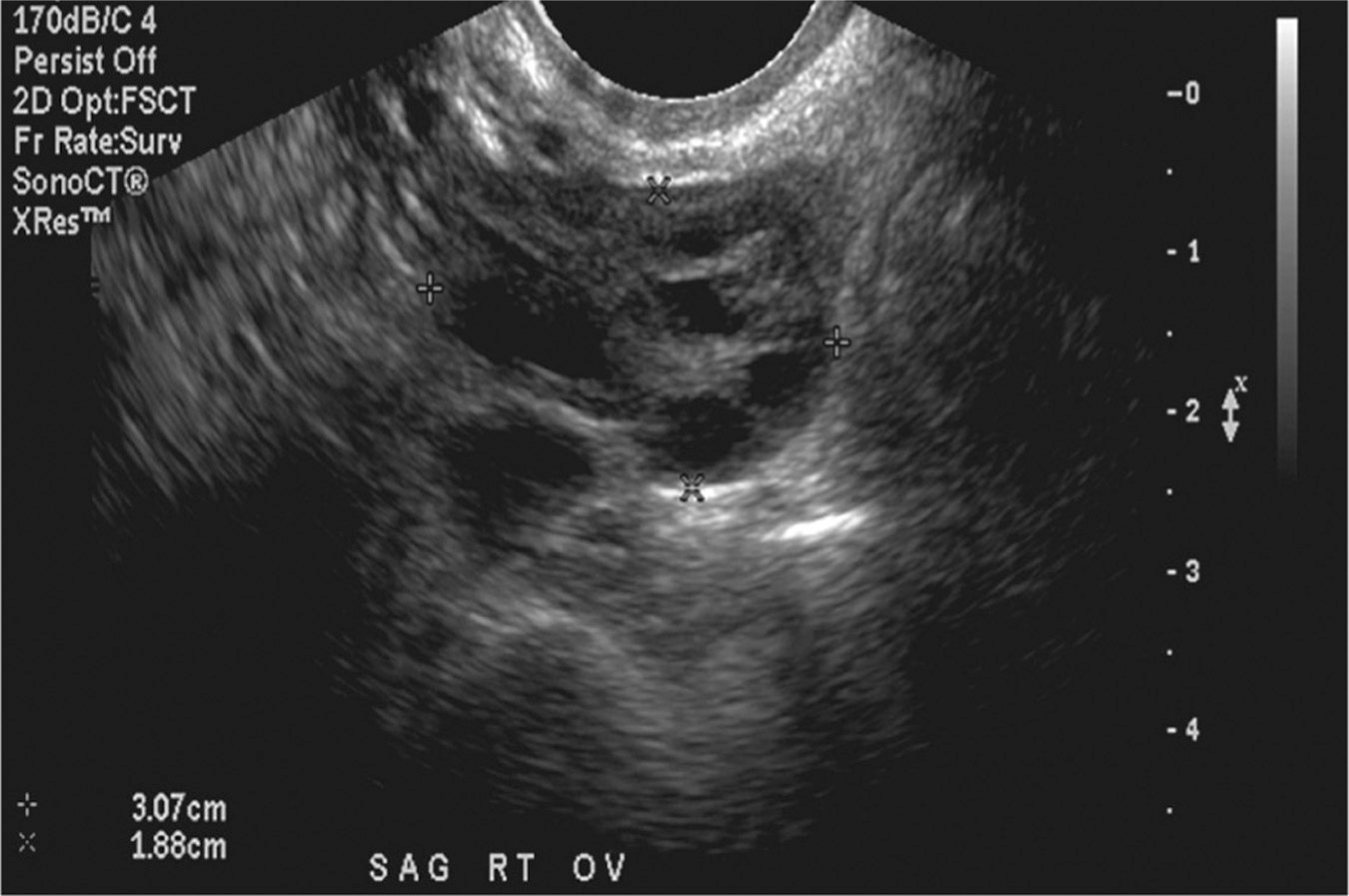

In 2010, the Society for Radiologists in Ultrasound (SRU) released a consensus statement on the recommended management and follow-up for adnexal masses that are incidentally seen on US in asymptomatic, nonpregnant women (Levine et al., 2010). Although the guidelines are intended for masses in the nonpregnant population, other studies have utilized similar management in pregnant women (Hoover & Jenkins, 2011; Schmeler et al., 2005; Zanetta et al., 2001). These guidelines allow stratification of adnexal masses into those that require further follow-up and those that do not on the basis of the presence of features suggestive of malignancy or benignity. The guidelines for premenopausal women include the following: normal ovaries are typically less than 3 cm in size, round or oval with thin smooth walls, anechoic spaces, and no flow seen on color Doppler US. Ovaries may contain multiple physiologic follicles or simple cysts that are considered normal if they measure less than 3 cm. The corpus luteum appears as a thick-walled cyst with or without crenulated inner margins, measures less than 3 cm, and often has internal echoes with a peripheral ring of vascularity on color Doppler US. Physiologic cysts (Figure 7.1) and corpus luteum cysts (Figure 7.2) do not require further follow-up.

Simple cysts as noted in Figure 7.3 that are anechoic with smooth thin walls measuring 5 to 7 cm without any features of complexity may be followed with annual repeat imaging in premenopausal women. Those measuring greater than 7 cm can be further evaluated with additional imaging or surgical evaluation if clinically indicated.

Figure 7.1 Normal ovary with physiologic follicles

Source: Courtesy of the Department of Radiology, Women & Infants Hospital, Providence, RI.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree