Pain in the lumbar spine primarily arises in the two inferior lumbar vertebral motor segments, i. e., L4/L5 and L5/S1. One reason why the most marked disorders of form and function are found here is because of the exceptional loading placed on the inferior lumbar spine. Another reason is that spinal nerves and their efferent branches are found in the immediate vicinity. The sacroiliac joints also usually contribute to this painful situation. They belong functionally to the inferior lumbar vertebral motor segments, and the dorsal ramus of the spinal nerve connects them with the S1 nerve root. The special topographical relationship between the musculoskeletal system and the nervous system in this region is of particular importance not only to pain therapists, but also to surgeons.

Specialized Lumbar Neuroanatomy

The vertebral body and the intervertebral disk form the anterior border of the lumbar spinal canal, the ligamentum flavum and the vertebral arch the posterior border. The pedicles and the intervertebral foramina are found laterally. The lumbar vertebral canal is a cylindrical cavity that changes its shape and volume with every movement of the trunk: Trunk flexion increases its volume, and trunk extension causes it to narrow.

The contents of the lumbar vertebral canal include the dural sac, nerve roots, and peridural tissue. This consists of veins and fatty tissue and encases the nerve root, ensuring that it is protected from the bony borders of the vertebral canal even during extreme movements of the lumbar spine.

The displacement of spinal cord segments in relation to their corresponding motor segment in the vertebral column is at its most extreme in the lumbar spine. The inferior end of the spinal cord extends only to the first or second lumbar vertebra. The spinal nerves exit the vertebral canal through their corresponding intervertebral foramina inferior to this, and travel for a long distance in the subarachnoid space, where they are usually found laterally. There is thus no need to worry about nerve injuries when conducting medial lumbar punctures and myelography, or during transdural disk punctures.

Paramedian protrusions and prolapses can cause the intrathecal compression of spinal nerves and more deeply situated nerve root syndromes. The entire length of the long inferior spinal nerves and the filum terminale, the final fibers of the spinal cord that extend down to the second coccygeal vertebra, is called the cauda equina.

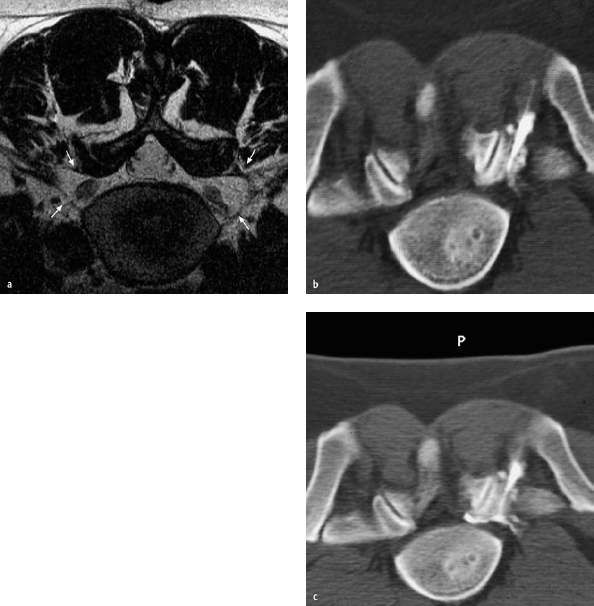

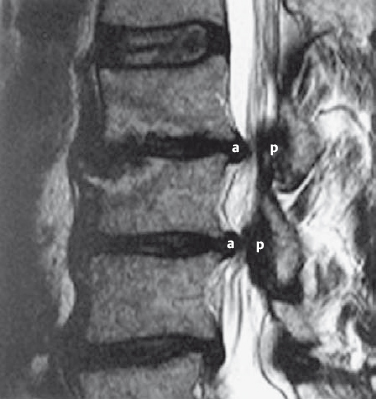

After leaving the dural sac, the nerve root travels in a direction dictated by the segmental level. The more inferior the nerve root, the more acutely angled it is as it exits the dural sac. This explains why different topographical relationships are observable between each nerve root and intervertebral disk in the lumbar vertebral motor segments segments. The exit point for the L4 nerve root is found at the same level as the L3 vertebral body, the L5 nerve root exits the dural sac at the height of the inferior edge of the L4 vertebral body, and the S1 nerve root at the inferior edge of the L5 vertebral body (Fig. 9.1).

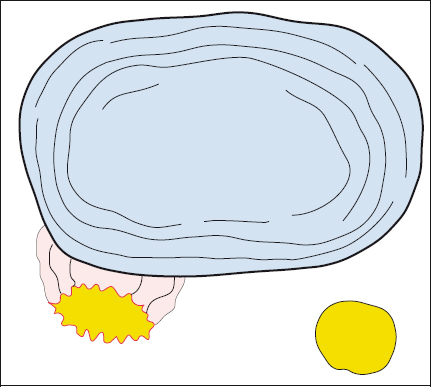

A L4/5 intervertebral disk prolapse (Fig. 9.1, arrows) exerts pressure primarily on the L5 nerve root. The L4 nerve root is affected only when the prolapse is very large and is displaced in a lateral or superior direction, as a result of the L4 nerve root passing superior to the L4/5 intervertebral disk. The S1 and L5 nerve roots can be affected at the same time at the L5/S1 intervertebral segment, even by a small lateral prolapse (Fig. 9.1, arrows). The L5 spinal nerve root lies in the upper section of the intervertebral foramen, directly on the outer lamellae of the intervertebral disk. The L5 nerve root has only a very small amount of free space within the L5/S1 intervertebral foramen. The lumbar nerve roots are affected by intervertebral disks only in the two inferior segments: It is here that there is the most danger of compression arising from an intervertebral disk.

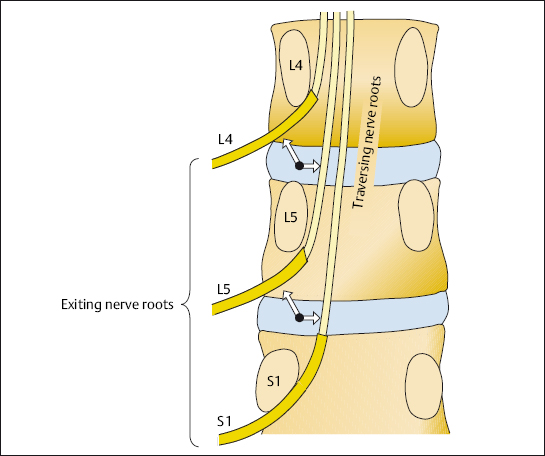

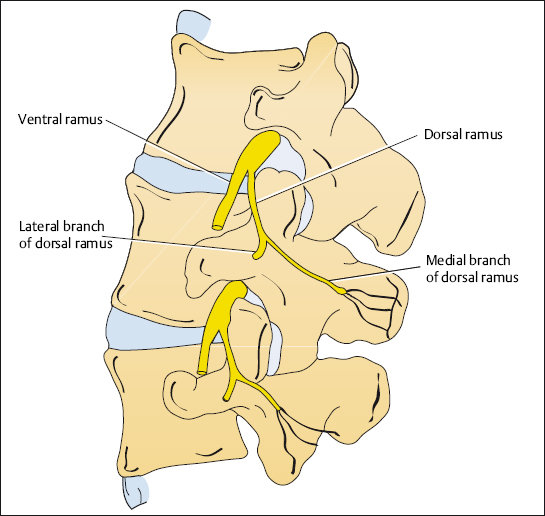

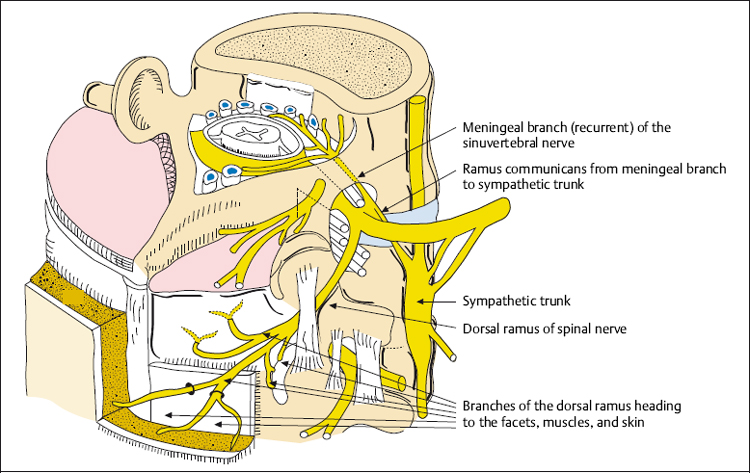

The foraminal articular region, with the spinal nerves exiting the intervertebral foramen and the efferent nerve branches, is of particular interest. Directly after its exit from the intervertebral foramen, the spinal nerve divides into a thicker ventral ramus, a somewhat thinner dorsal ramus, and a tiny sinuvertebral nerve. The dorsal ramus divides into a lateral branch that runs to the facets and a medial branch that runs to the spinous process (Fig. 9.2). The recurrent branch (meningeal branch, sinuvertebral nerve, see Fig. 9.3) passes through the intervertebral foramen, back into the spinal canal, and innervates the rear section of the anulus fibrosus, the posterior longitudinal ligament, and the dura.

Figure 9.3 (second spinal nerve) demonstrates how close the spinal nerves and their branches are to the muscles and joints, and also to the sympathetic trunk via the ramus communicans connection in the foraminal articular region of the inferior lumbar vertebral motor segments. Nociceptors in the joint capsule, the posterior longitudinal ligament, and the periosteum of the vertebral body are located in close proximity to the afferent fibers of various nerves. Disorders of form and function in the musculoskeletal system cause reactive changes in the joint capsule and outer edges of the vertebral body as a result of intervertebral disk degeneration. At the same time, this causes irritation of the nociceptors found there, leading to neuralgia when afferent fibers are irritated over a longer period of time. The autonomic reaction is directly and indirectly involved as a result of the irritation of the ramus communicans from the meningeal branch to the sympathetic trunk and via the spinal nociceptive reflex arc (see Chapter 1, “Moving from Acute to Chronic Pain: Nociceptor Sensitization”).

Fig. 9.2 Lumbar spinal nerve with ventral ramus and dorsal ramus (according to: Bogduk 1997).

Fig. 9.3 The spinal nerve with its branches (from: Bogduk 1997).

The foraminal articular region of the lower lumbar vertebral motor segments is particularly important in the development and treatment of chronic back pain and sciatica. Obviously the nociceptive neuralgic structures, located so close to each other, are suited for local treatment, e. g., infiltration.

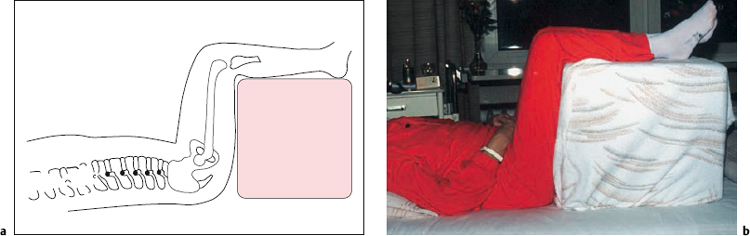

Basic Therapy for Lumbar Pain

General therapeutic measures, such as bed rest, heat treatment, massage, electrotherapy, and analgesics, act in some way on the vicious cycle of pain–tense muscles–pain, resulting in freedom from pain in mild cases. The lumbar intervertebral disks experience the least amount of loading when the patient is positioned horizontally with the lumbar lordosis flattened out and the hip and knee joints flexed. For this reason, the use of the so-called Fowler position is recommended as the first treatment measure (Fig. 9.4a, b).

Heat, in the form of mud packs, heat pads, or infrared treatment, acts to relieve pain and muscle tension. Analgesics and anti-inflammatories are additionally administered when pain is very severe (see Chapter 4, “Multimodal Medication Concomitant Therapy”).

Massage and electrotherapy are first administered in acute lumbar syndromes after the acute symptoms have been largely relieved by positioning, heat treatment, and analgesics. Electrotherapy is administered using high frequency, low frequency, and interferential currents (see Chapter 4, “Electrotherapy”).

Ultrasound relaxes ligamentous and insertion tendopathies, especially in the region of the interspinous ligaments and the short back muscles. Diadynamic currents have a deep analgesic effect at the nerve roots and their branches. Deeper-lying spinal structures can also be reached by the use of short wave radiation.

Manual therapy is indicated in the treatment of lumbar spinal pain when acute local zygapophysial joint or sacroiliac joint symptoms are present, or when another functional disorder is the focus of attention. This is precisely ascertained using manual assessment techniques. Manual therapy should be used with caution when intradiscal mass displacement, protrusions, and prolapses are present as manipulation can sometimes increase the degree of protrusion.

If the anulus fibrosus is intact, the use of traction enables displaced intervertebral disk tissue to return to the center of the disk. Several options are available for traction in the lumbar spine region, including self-traction, permanent traction devices positioned on the iliac crest, or traction belts (Kraemer 2009). The physician fits these orthopedic aids individually according to how treatment is progressing, on the basis of clinical neurological signs which must be reassessed at regular intervals.

Traction on an inclined bed or traction table, or using Perl’s apparatus, has now been replaced by the more manageable flexion cube, which repositions lumbar intervertebral disk protrusions in the same way, combined with heat treatment.

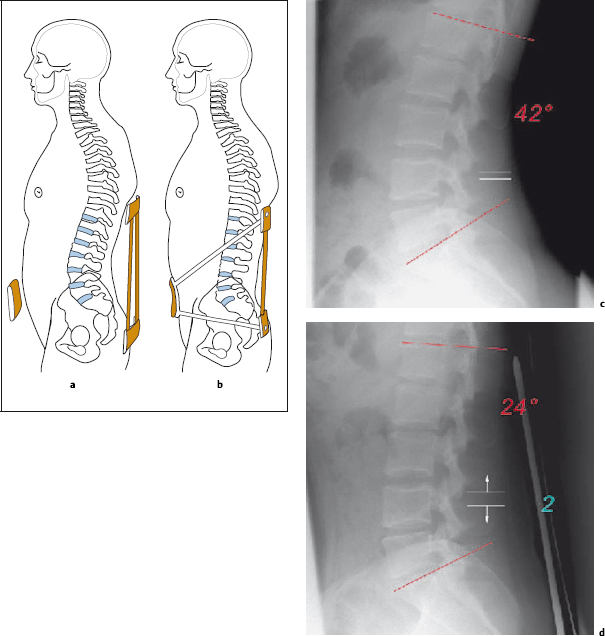

The supportive and corrective function of flexion orthoses is useful in the treatment of acute and chronic pain in the lumbar spine that is caused by the displacement of intradiscal mass and a hyperlordotic position of the zygapophyseal joints. Their use is also indicated in postsurgical segmental instability, e. g., following discotomy, percutaneous nucleotomy, or chemonucleolysis. Degenerative instability with hight reduction in the posterior section of the vertebral motor segment is also an indication for the use of orthoses, which should reduce loading on the vertebral motor segment by increasing intra-abdominal pressure and flattening out the lumbar lordosis. This flattening leads to widening of the intervertebral foramina and the spinal canal (Fig. 9.5a–d).

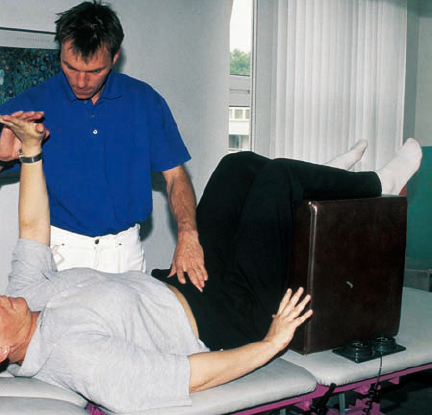

During physiotherapy, pain is relieved by using traction in a neutral position. This is usually conducted in a relaxed position with the legs raised in the Fowler position (Fig. 9.6). When acute pain is present, this is in fact the only possible starting position. The patient is placed in this initial position and attempts to move normally and to stabilize the affected spinal region at the same time. As the symptoms start to diminish, other starting positions can be used until the lordosis is normal again.

Movement Program (MIPFR) for the Lumbar Spine

Movement Program (MIPFR) for the Lumbar Spine

The first rule of back school is, “Keep moving.” With this in mind, all types of movement that do not provoke back pain are appropriate, based on the movement in pain-free range (MIPFR; see Chapter 3.5) principle. Central to the movement program for chronic back pain are back friendly sports which use linear movements, e. g., swimming, jogging, and cycling. Other patterns of movement are also appropriate as long as the patient does not adapt an excessively lordotic posture or thoracic kyphosis combined with rotary movements. The sports or types of exercise recommended in the individual treatment program should be ones the patient mentioned as favorites in their initial assessment, so that exercises are conducted daily and regularly.

Special Therapy for Lumbar Pain

Local Pain Syndromes in the Lumbar Spine (Local Lumbar Syndrome, Nonspecific Back Pain)

By definition, the pain caused by local lumbar syndromes is restricted to the lumbosacral region, i. e., there is no radiation into the lower limbs. The back pain is felt at its point of origin, so we are dealing with a nociceptively governed clinical picture.

The pain arises in the nociceptors of the zygapophyseal joint capsules, the posterior longitudinal ligament, and the interspinous ligaments. The nociceptors found in the muscle attachments and the long and short back muscles themselves are secondarily affected. The sensitive fibers of the meningeal branch and the dorsal ramus of the spinal nerve are predominantly affected. The permanent reflex tension in the back extensor muscles is perceived as unpleasant and painful. These patients suffer from position dependent back pain, muscle tension, and restricted mobility of the lumbar spine. The different symptoms found in the local lumbar syndrome are often summarized in the term “nonspecific back pain,” especially when the examiner is unable to assess precisely where the pain is originating from.

In order to target the local treatment of back pain, it is important to know where the pain originates, i. e., the zygapophyseal joint, back muscles, or sacroiliac joints. Important information is gained from the medical history and the results of the manual therapy assessment. Many investigators have indicated the importance of the zygapophyseal joints in the development of back pain (Ghormley 1933, Badley 1941, Mooney 1976, McCall et al. 1979, Carrera 1980, Young 1983, Law et al. 1985, Moran et al. 1988).

The symptoms can begin suddenly, e. g., when the trunk is abruptly rotated, or may arise gradually without any special reason. During the subjective assessment patients often mention exposure to cold or remaining in the same posture for some time among the precipitating factors. During the examination, the patient can quite clearly localize where the pain is coming from, in the initial stages. Pain is usually felt more on one side in the region of the sacroiliac joints and the lumbar back extensors. This is in the area supplied by the posterior branch of the L5 and S1 nerve roots. Permanent irritation of the dorsal ramus results in the development of a neuralgia-governed component, where pain spreads into the proximal sections of the lower limb and cannot be allocated to a specific segment, e. g., in the buttock region. Patients present with the typical tender points at the spinous processes and along the posterior section of the sacroiliac joints. In addition, the back extensors are distinctly under a certain amount of tension and the mobility of the lumbar spine is restricted. When acute pain syndromes are present, a motor reaction causes the patient to immediately adopt a posture of slight trunk flexion and, in some cases, lateral flexion (Fig. 9.7). This posture should not be altered, as it represents a protective reflex which aims to prevent further irritation of the nociceptors in the zygapophyseal joint capsule and the posterior longitudinal ligament.

Treatment of Acute Low Back Pain

The main aim of treatment in acute local lumbar syndromes is the immediate removal of pain, interrupting the chronification process right from the start. Peripherally acting analgesics (see Chapter 4, “Multimodal Medication Concomitant Therapy”) block nociception and the distribution of pain signals at their point of origin. The simultaneous administration of local infiltrations at the source of pain is recommended. The source of pain is ascertained during the manual therapy assessment and by trial injections. The interspinous ligament insertions, usually between L4/L5 and L5/S1, as well as the zygapophyseal joint capsules, are suspected when acute arthroligamentous back pain is present. When pain is felt more on one side, the back extensors tense up asymmetrically and one sacroiliac joint is also often included in the primary painful event. Immediate mobilization (manual therapy), with the support of local infiltration with local anesthetics and concurrent electrotherapy, prevents a permanent blockage in the affected zygapophyseal and sacroiliac joints.

In this phase patients immediately accept the rules of back school, as incorrect posture and behavioral patterns immediately cause severe pain. Patients should be familiarized with these rules from the very beginning to prevent recurrence of pain and the evolution of chronic pain. As long as they do not attempt heavy physical labor, even patients with acute low back pain can pursue their accustomed way of life with only slight restrictions if they follow the postural and behavioral guidelines learned from back school. They can continue to walk, sit, stand, and carry out tasks involving light to moderate physical labor.

Controlled studies into acute low back pain (Coomes 1961, Gilbert et al. 1985, Postacchini et al. 1988, Deyo et al. 1991, Szpalski and Hayez 1992, Malmivaara et al. 1995, and Wilkinson 1995) have demonstrated that bed rest and immobilization impede the healing process rather than helping it. Therapeutic approaches that use centrally depressing medication are therefore obviously inappropriate. The emphasis should be on interventions that affect the nociceptive region locally. Treating physicians should choose the method that they are most familiar and comfortable with from the range of therapies that conform to this concept (Table 9.1)

Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain

Pain that endures for weeks or months is at risk of becoming chronic. Patients find it more difficult to retain their accustomed way of life, and psychological disturbances are inevitable. The pain changes in character and is permanently present, sometimes even during the night.

Initially, the pain is selectively located at a zygapophyseal joint or in the area surrounding a sacroiliac joint. This develops into a diffuse pain in the lower back that spreads over the entire lumbosacral region. It can spread into one or both limbs as a pseudoradicular form of pain. The permanent tension in the back extensors and the proximal limb muscles causes insertion tendopathies at the pelvis, the spinous processes, and eventually also in the upper sections of the trunk.

Fig. 9.7 The adaptive posture seen in an acute lumbar syndrome (lumbago) with the trunk slightly bent forward and laterally flexed.

| Analgesics |

| Pain-relieving position |

| Cryotherapy (heat therapy) |

| Local infiltrations (trigger points, facets, SIJ) |

| Manual therapy (traction) |

Treatment consists primarily of heat treatment, exercises, and local infiltration at the initial and secondary sources of pain. Analgesics and sedatives should be administered with caution in cases of chronic low back pain, as side effects are more likely when they are used long term.

Treatment for a chronic lumbar syndrome aims primarily to break the vicious cycle of pain–cramped muscles–adaptive posture–pain at the muscular level. Massage, electrotherapy, infiltration of muscles using local anesthetics, and general measures used to relax muscles are ideal for this purpose. Progressive muscle relaxation according to Jacobson (1938) is the primary intervention used to achieve this. The increased muscle tension originally served a useful purpose, but as the chronically recurring lumbar syndrome progresses it becomes an independent part of the vicious cycle. This results in pain caused by constant muscle tension and insertion tendopathies.

| Heat |

| Local injections |

| Back school |

| Psychotherapy |

| Progressive muscle relaxation |

Fig. 9.8 The typical adaptive posture for acute sciatica on the right-hand side.

When the pathological muscle tension has eased as a result of heat treatment, electrotherapy, or distraction, the use of exercise is appropriate provided it is performed carefully and in the pain-free range of movement. Possibilities include stationary cycling and swimming backstroke in a stress-relieving posture. Back school postural and behavioral training dictates that all movements and postures that can result in new nociceptive input must be completely avoided. In the chronic lumbar syndrome, this mainly means avoiding extension and rotary movements of the lumbar spine, excessive kyphotic postures, or maintenance of the same posture for a long time. The exposure of muscles to cold, or psychological stress, can also assist the chronification process (Table 9.2).

Pain Therapy for the Lumbar Nerve Root Syndrome

Dermatomal spread of pain into the leg indicates the irritation of a spinal nerve, with the involvement in particular of the ventral ramus. This is a neuralgia-governed clinical picture. Generally speaking, the spinal nerves belonging to the two most inferior lumbar vertebral motor segments are affected and patients present with symptoms of sciatica.

Lumbar nerve root syndromes are caused by intervertebral disk protrusions or prolapses and/or bony impingement in the lateral recess and in the intervertebral foramen. The clinical symptoms associated with discogenic sciatica arise suddenly in most cases and quickly adopt neuralgic characteristics. The afferent fibers in the spinal nerve are rapidly converted to nociceptors. Pain that is position-dependent, accompanied by a feeling of numbness or ants crawling along the dermatome, is characteristic of this disorder (Fig. 9.8). The neuralgia can be accentuated by external factors such as axial loading, sudden changes in posture, and bending the trunk.

In the lumbar nerve root syndrome pain chronification is predetermined because of the neuralgia. The lumbar nerve root syndrome is a primary chronic disorder: The conversion of a primary conducting nerve to a nerve with a nociceptor function already signifies chronicity. The longer the condition remains, the less chance there is that simple forms of intervention, such as manipulation, traction, or a nerve root block, can rapidly improve the pain. The constant irritation of the spinal nerve root leads to secondary symptoms with motor and autonomic reactions. In the course of time, central changes occur in the perception and processing of pain. In some cases, characteristics such as different positions affecting pain levels and the day-night pattern can no longer be observed: Pain is felt permanently, and associated psychological symptoms appear. The constant maladaptive postures cause muscle tension and insertion tendopathies not only in the lumbar region, but also in the upper sections of the trunk.

Pain therapy for the lumbar nerve root syndrome targets not only the peripheral nociception, but also the transmission and processing of pain signals; local injections using lumbar spinal nerve analgesia and epidural injections are the main focus. In both acute and chronic lumbar nerve root syndromes it is advisable to tackle the point of nerve root compression directly (see Chapter 11).

Pain Therapy for Lumbar Spinal Canal Stenosis

The characteristic pain arising from a lumbar spinal canal stenosis varies according to the amount of weight-bearing when walking and standing, and is reduced by all postures involving trunk flexion (flattening out the lordosis). This differs from the ischemic pain caused by circulatory disorders. Leg pain is the main symptom. It presents as bilateral pain that is found especially along the anterior side of the thigh in the case of central spinal canal stenosis and as an ipsilateral dermatomal spread in the case of lateral spinal canal stenosis. The leg pain often develops after walking for only a few steps, and is therefore also described as intermittent spinal claudication.

Possible causes for the constriction in the lumbar vertebral canal include bony involvement (vertebral arch, vertebral body) as well as the involvement of soft tissue structures (intervertebral disk, connective tissue). Spinal canal stenosis can occur in one segment or in several segments, depending on the cause. In most cases, the epidural space is characteristically narrowed by the ligamentum flavum protruding from the posterior side and the degenerative changes found in the intervertebral disk from the anterior side (Fig. 9.9). Both of these protrusions develop as part of the degenerative narrowing of the intervertebral section. Hyperlordosis amplifies these phenomena. These deformations are initially symptom-free and are described as compensated spinal canal stenosis. An increase in the lumbar lordosis due to age-related abdominal muscle weakness, small amounts of intradiscal mass displacement with the amplification of one or more intervertebral disk protrusions, and postural and behavioral changes with an associated increase in the lumbar lordosis additionally narrow the space available for the neural elements in the lumbar vertebral canal. This continues until there is no more space available and leads to the development of a compression-related pain.

Decompensated Spinal Canal Stenosis

Compression-related nerve root edema and congested epidural veins lead to the rapid development of spinal canal syndrome, which is accompanied by severe pain in both legs. This can occur in one segment or several. As it is mainly spinal nerves that are being compromised, the pain is dominated by neuralgia. According to Porter (1985), the neurogenic intermittent claudication associated with spinal canal stenosis never exceeds a certain level and does not result in paraplegia.

Because of the neuralgic character of the pain, centrally acting analgesics are administered as part of the symptomatic pain therapy for lumbar spinal canal stenosis with the aim of maintaining the mobility of the (mainly older) patients. The disorder of venous drainage in the spinal canal should be treated with agents that stimulate blood flow. The spinal nerve roots that are compromised in the vertebral canal are best reached by the use of epidural injections. In the case of a central spinal canal stenosis involving several segments, the use of a posterior epidural injection is appropriate as several segments can be reached at the same time. When patients present with a lateral spinal canal stenosis with compression of a single spinal nerve in the lateral recess or in the intervertebral foramen, an epidural perineural injection is indicated. Spinal nerve analgesia and facet infiltration are administered to complement the treatment, addressing the hyperlordosis and the tense lumbar muscles.

Fig. 9.9 Sagittal MRI section of the lumbar spine; spinal canal stenosis at two levels with protrusion of the intervertebral disks from anterior (a) and the ligamentum flavum from posterior (p).

Causal pain therapy aims to flatten out the lumbar lordosis and thus significantly widen the lumbar vertebral canal. This additionally flattens intervertebral disk protrusions on the anterior side of the spinal canal and the protruding ligamentum flavum on the posterior side. The lumbar lordosis immediately flattens out when the patient is placed in the Fowler position and wears a flexion orthosis while standing and walking. Physiotherapy focuses mainly on strengthening the abdominal muscles. Twice daily stationary cycling (mornings and afternoons for 30 min) complements the physiotherapy program when conducted as MIPFR (Table 9.3).

Surgical widening of the lumbar spinal canal is an option when the disorder is resistant to treatment. It was common in the past to widen the spinal canal using a laminectomy over several levels. Nowadays, surgical intervention is limited to microdecompression at the affected segment. This is based on the knowledge that spinal canal stenosis is caused only by intervertebral disk involvement or the narrowing of a recessed area.

| Symptomatic | Causal |

|---|---|

| Psychological pain therapy Central analgesia | Fowler position |

| Stimulation of venous blood flow | Physiotherapy from the pain-relieving position |

| Epidural injection | Stationary cycling (MIPFR) |

| Spinal nerve analgesia | Flexion orthosis |

| Facet infiltrations | Decompression surger |

Fig. 9.10 MRI scan of a patient suffering from a postdiscotomy syndrome following an open lumbar intervertebral disk operation at the L4/5 segment. A surgical scar can be seen on the right-hand side. It extends continually from the skin, via the subcutaneous tissue and the back extensors, into the inner space of the lumbar vertebral canal. The scar tissue then extends further, passing between the dura and the vertebral canal, affecting the traversing and exiting nerve roots, and extends as far as the intervertebral disk. Movement of the (degenerative or surgically) unstable intervertebral segment is transferred anteriorly directly to the scar and the entrapped neuropathically modified nerve root. Likewise, movement in the back muscles is transferred posteriorly to the nerve root by the pull on the scar.

Pain Therapy for Problem Patients Who Have Undergone Spinal Surgery

These patients still have back and leg pain even after one or several intervertebral disk operations or surgical fusions. Chronic pain arises both from the peripheral nociception in the vertebral motor segment and in the neurologically modified nerve fibers. There is therefore a mixture of nociceptive and neuralgia-governed pain symptoms. The particular characteristic of pain chronification in postsurgical patients is that the actual operation on the spine (either open intervertebral disk surgery or spinal fusion surgery) involved nociceptors that were already sensitized and nerve fibers that were already modified into nociceptors. Direct intraoperative trauma to the nociceptors and the neurologically modified nerves in the area of the wound has led to further permanent damage. Postsurgical scar tissue is formed, with the involvement of neural structures that have previously been neuropathically damaged (Figure 9.10). These neuropathically modified nerves and sensitized nociceptors, which are repeatedly irritated by tension in the scar tissue, form the pathological and anatomical substrate for chronic pain in patients who have already undergone spinal surgery.

Character and Severity of Pain

Character and Severity of Pain

The pain in these cases is characterized by a bilateral, mixed pseudoradicular/radicular set of symptoms. Frequently, several nerve roots are involved. Neurological deficits may also be the result of previous operations and should not always be attributed to the current clinical picture. Severe neurological disorders are quite rare: Although the nerve root is strangulated by the scar tissue, it is not completely severed. Pseudoradicular components and nociceptively amplified pain are the result of segmental instability with irritation of the zygapophyseal joint capsule and the nociception in the posterior longitudinal ligament. These patients have only a small pain-free range of movement because spinal nerve roots and their branches, now partly fixated by scar tissue, have been partially severed during surgery leaving free nerve endings.

NOTE

The strands of connective tissue along the dura and nerve root can be compared to wind chimes that are stirred into action by any kind of careless movement.

| Bilateral, mixed pseudoradicular/radicular symptoms |

| Double-sided positive Lasègue test |

| Impossible to flex trunk or sit with legs extended |

| Epidural scarring seen on MRI and CT |

Nociceptors and afferent fibers are in a permanently irritated state. Inflammatory and edematous processes cause swelling in the spinal nerves and further narrow what space is left in the vertebral canal. A vicious cycle begins. The mobility of the sciatic nerve root during trunk flexion is most affected. This is noticeable when the leg is extended and raised, or when the patient sits with straightened legs. In severe postsurgical pain syndromes, the Lasègue test is bilaterally positive after only 10–20° of movement. The mobility of dura and nerve roots in the vertebral canal is often so limited that even flexing the neck aggravates the typical range of symptoms (Table 9.4, Fig. 9.11).

Patients with a pronounced postdiscotomy syndrome following one or several intervertebral disk operations are considerably impaired: They are unable to sit, stand, or lie down normally (Fig. 9.12). As they have no serious neurological deficits, these patients are often labeled as “pension neurotics” or categorized as suffering from psychological overlay.

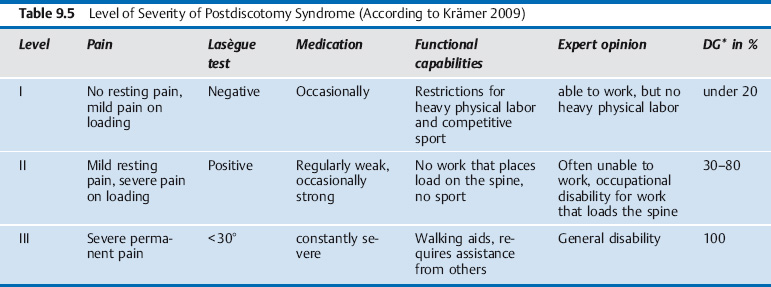

The severity of a postdiscotomy syndrome is primarily determined by the subjective level of impairment. Objective criteria, such as neurological deficits, scarring, and instability, are not always an accurate measure of severity. Several consultations with the patient may be necessary to define their amount of suffering, with different people observing. The straight-leg-raise test in lying and sitting is relatively reliable, as is observing the patient when they sit with their legs extended, take off and put on their shoes and socks, and flex the trunk during other activities (Table 9.5).

Therapy Approaches

Therapy Approaches

The pain therapy approach for problem patients who have previously undergone back surgery is multifaceted. It corresponds to the patient’s mixture of nociceptive and neuralgic symptoms and the associated significant changes in pain transmission and perception. Either peripherally or centrally acting analgesics are administered, depending on whether the nociceptive or neuralgic component is more prominent. As the centralization process is usually quite advanced, most patients report that only centrally acting analgesics bring relief (Theodoridis et al. 2004).

Local injection therapy is used to directly influence the nociception and neuralgia in the previously operated vertebral motor segment. The use of epidural injections and spinal nerve analgesia at the affected segments is well established. When administering interlaminar epidural injections using the loss-of-resistance technique, injections must be placed one or two segments higher or access obtained via the sacral canal (as an epidural sacral injection). This is necessary because of the adhesions found in the epidural space at the surgical site. The epidural perineural injection technique is the best way of directly influencing the entrapped, edematously swollen nerve root. Intradiscal injections maybe considered if the postsurgical MRI or CT still shows a broad-based dent caused by an intervertebral disk protrusion.

Fig. 9.11 The slightest change in the volume and consistency of the intervertebral disk causes a reaction in the disk and the nerve root because these two structures are connected by scar tissue.

Fig. 9.12 A patient with a pronounced postdiscotomy syndrome following several intervertebral disk operations, who has considerable functional limitations in daily life and can mobilize only with the use of walking aids.

| Symptomatic | Causal |

|---|---|

| Analgesics (central and peripheral) | Stabilization of the trunk muscles, physiotherapy |

| Psychological pain therapy | Psychological pain therapy |

| Local injections | Back school |

| Alternative medicine | Orthosis (temporary) |

| Movement therapy | Spondylodesis |

Chronic pain conditions originate mainly in the dorsal ramus and are treated with facet infiltrations and scar infiltrations.

To treat instability, the second pathogenetic component in the postdiscotomy syndrome, it is worth trialing the use of a trunk orthosis. Flexion orthoses that relieve loading on the posterior section of the vertebral motor segment seem to be appropriate. Concurrent physiotherapy with isometric stabilizing exercises starting in a pain-relieving position is essential. The trunk muscles are trained using intensive exercises. The ultimate aim is for these muscles to take over the function of the orthosis and contribute to the stabilization of the previously operated vertebral motor segments.

Multifaceted pain therapy is justified in the treatment of the postdiscotomy syndrome because of the syndrome’s multifaceted etiology and pathogenesis and its equally multifaceted set of symptoms. All types of intervention that do not cause additional damage to the patient are important. The body’s own pain-inhibiting mechanisms should be activated as much as possible. This includes all of the psychological measures available to cope with and reduce the pain, as well as the use of an individually tailored movement program (MIPFR; Table 9.6).

Pain Following Lumbar Spondylodesis

A posterior, anterior, or posterior/anterior spondylodesis at the affected vertebral motor segment is a surgical treatment option when all conservative measures that aim to stabilize the surgically unstable segment have failed. This operation is also performed when post-traumatic instabilities and deformations (e. g., spondylolisthesis) are present. The main indication worldwide is nevertheless the problem patient who has previously undergone one or more intervertebral disk operations. By eliminating the instability component, it is usually possible to relieve a large proportion of the pain in postdiscotomy syndromes. However, new pain symptoms often develop, originating in the neighboring segments or the sacroiliac joints. This pain complex is called the postfusion syndrome (Krämer 2009). The pain arising from the segment instability near the fusion site, the sacroiliac joints, and the new scar tissue is then combined with the residual pain coming from the postdiscotomy syndrome.

The pain therapy approach for this particularly problematic group of postsurgical patients is largely the same as for the postdiscotomy syndrome. The predominant set of local symptoms has to be identified using clinical neurological examinations and, in particular, trial local infiltrations. The psychological care of these patients is particularly important. After undergoing repeated and sometimes very complicated operations, they are very skeptical about any type of medical intervention and tend to prefer long-term medication with centrally acting analgesics.

Exercise Program

Exercise Program

The exercise program aims to make use of the limited pain-free range available. Back surgery patients with severe pain can once again exercise without running the risk of their pain increasing during or following activity— mainly swimming, cycling, and some suitable exercises. The sports instructor should focus on expanding the patient’s possible movement spectrum by introducing him or her to other patterns of movement, such as jogging under minimal loading, aqua-jogging, Thera-Band exercises in a lying position, etc. For many patients, it is quite an experience to be able to move more without experiencing pain.

Lumbar Injection Therapy

Lumbar Spinal Nerve Analgesia

Principle

Posterolateral injection of a local anesthetic (mixed with steroids, when necessary) into the foraminal articular region of the vertebral motor segment.

Topographical and anatomical palpation points determine the injection angle and needle path. The lumbar spinal nerve analgesia differs from the Reischauer (1953) and Macnab and Dali (1971) techniques in that the needle is placed at an angle rather than in a sagittal direction. The injection site is 8–10 cm lateral to the midline and the needle is inserted at an angle of approximately 60°. Using this method, bony contact is always established with the posterolateral section of the lumbar vertebra.

Indication

All acute and chronic local and radicular lumbar syndromes are indications for lumbar spinal nerve alalgesia (LSPA). However, other forms of lumbar vertebral motor segment irritation caused by osteoporotic fracture, spondylolyses, tumor-related pain, spinal canal stenoses, and inflammatory pathological changes, particularly in the area of the vertebral joint capsule, also respond well to this method of treatment (Table 9.7).

Technique

The needle is 10–15 cm long (usually 12 cm), depending on the soft tissue depth. The intervertebral foramina of the inferior lumbar spine are best reached by inserting the needle 8 cm lateral to the midline at the same level as the iliac crests. The needle is placed at a 60° angle in the horizontal plane and at different angles in the vertical plane depending on which nerve root is affected:

- To infiltrate the L3 nerve root, the needle is inserted at an angle of 0°.

- To infiltrate the L4 nerve root, the needle is inserted at an angle of 30°.

The needle is inserted superior to the L5 transverse process for 1–2 cm until bony contact is made. The tip of the needle is then positioned on the lateral facet, immediately next to the intervertebral foramen, or along the side wall of the vertebral body. It is here that the ventral ramus, the efferent branches of the dorsal ramus, the meningeal branch, and the ramus communicans run down to the sympathetic trunk.

To infiltrate the L5 nerve root when it exits the L5/S1 intervertebral foramen, the needle tip is further lowered underneath the L5 transverse process, corresponding to an angle of approximately 50–60° in the vertical plane. The needle is inserted until bony contact is made with the lateral vertebral body or the lateral facet.

CT-monitored spinal nerve analgesia (Fig. 9.13a–c) has demonstrated that the injected solution disperses through the intervertebral foramen, additionally reaching the traversing S1 nerve root at the exact point where the L5/S1 intervertebral disk applies pressure onto the nerve.

It is possible for a root sheath to be punctured in the intervertebral foramen. For this reason, constant attempts to aspirate are made while the needle is being inserted, particularly during the final phase of the procedure. When contact is made with the nerve root, the patient indicates the presence of a sudden sharp pain radiating into the leg. This pain phenomenon can be largely prevented by proceeding slowly with continual pre-injection and aspiration. It is therefore recommended that a total of 10 mL of a dilute local anesthetic solution be used for the injection, as in the end usually only 4-5 mL are available for the actual injection at the target site. Once the final position of the needle has been correctly established, it is possible to add a longer-lasting local anesthetic (e. g., bupivacaine) and/or a glucocorticoid (e.g., 10mg triamcinolone) depending on the presenting clinical situation (Fig. 9.14).

| Local lumbar syndrome |

| Lumbar nerve root syndrome |

| Osteoporosis |

| Spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis |

| Tumor |

| Spinal canal stenosis |

| Rheumatic inflammatory changes to the vertebral columns |

| Postdiscotomy syndrome |