CELLULITIS

Cellulitis is a common infection of the skin or subcutaneous tissues with characteristic findings: erythema with poorly defined borders, edema, warmth, pain, and limitation of movement. Fever and constitutional symptoms may be present and are commonly associated with bacteremia. Predisposing factors include trauma, lymphatic or venous stasis, immunodeficiency (including diabetes mellitus), and foreign bodies. Common etiologic organisms include group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus in nonintertriginous skin, and gram-negative organisms or mixed flora in intertriginous skin and ulcerations. In immunocompromised hosts, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella species, Enterobacter species, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are common. In recent years, there has been a dramatic increase in the incidence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant S aureus (CA-MRSA), particularly in cellulitis associated with a cutaneous abscess. The differential diagnosis includes deep venous thrombosis (DVT), venous stasis, erythema nodosum, septic or inflammatory arthritis/bursitis, and allergic reactions.

Treatment of minor cases commonly consists of immobilization, elevation, analgesia, and oral β-lactam antibiotics with reevaluation in 48 hours. The increase in the incidence of CA-MRSA has prompted some, especially in highly endemic areas, to advocate coverage with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or other agents (refer to current recommendations) in addition to conventional β-lactam antibiotics. Admission and parenteral administration of antibiotics may be necessary for immunocompromised or toxic-appearing patients, or those who do not respond to outpatient therapy.

Rapidly progressive cellulitis or one that progresses despite treatment with β-lactam antibiotics should raise suspicion for CA-MRSA or deeper infections such as fasciitis.

Known risk factors for CA-MRSA include military personnel, prison inmates, and competitive sports players.

Routine blood or leading-edge cultures in nontoxic patients are generally low yield.

FELON

A felon is a pyogenic infection of the distal digital pulp space, with pus collecting in the spaces formed by the vertical septa anchoring the pad to the distal phalanx. This condition is characterized by severe pain, exquisite tenderness, and tense swelling of the distal digit with erythema. There may be a visible collection of pus or palpable fluctuance. Complications include deep ischemic necrosis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and suppurative tenosynovitis. The differential diagnosis includes paronychia, herpetic whitlow, and hematoma following traumatic injury.

Incision and drainage is generally necessary to treat a felon. To ensure complete drainage of the abscess cavity, all affected compartments should be entered. The packing of the abscess space is made with a small, loose-fitting wick to facilitate drainage. Oral antibiotics directed against gram-positive organisms should be used for 10 days and the packing removed or replaced after 24 to 48 hours. Consider treatment for CA-MRSA in addition to standard coverage in highly endemic areas.

Do not extend the incision proximal to the distal flexion crease.

Incisions should be made dorsal to the neurovascular bundle; the pincer surfaces (radial aspects of the index and long fingers and ulnar aspect of the thumb and small finger) should be avoided when possible.

“Hockey stick” and “fish mouth” incisions are associated with increased occurrence of unnecessary sequelae and are not recommended.

If there is radiographic evidence of osteomyelitis, or concern for tenosynovitis, consultation with a hand surgeon is required.

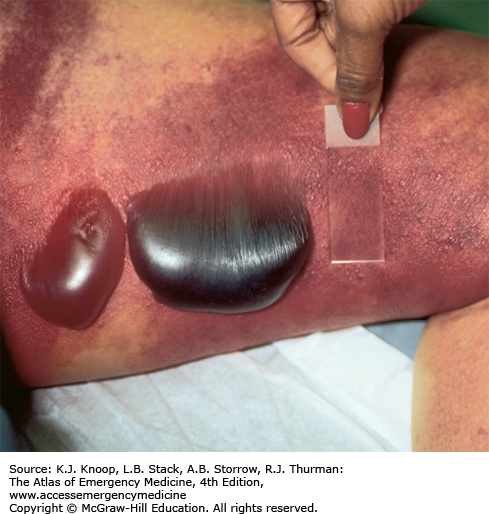

GANGRENE

Gangrene denotes tissue with lost blood supply and undergoing necrosis. The term dry gangrene is used for tissues undergoing sterile ischemic coagulative necrosis. Patients with atherosclerotic disease and diabetes are at risk for the development of dry gangrene, usually as a result of embolization to the forefoot or toe. Wet gangrene is associated with bacterial proteolytic decomposition, and is characterized by its moist appearance, frequently with blistering.

Hospitalization is usually required. The treatment consists of amputation, debridement, and antibiotic therapy as needed. Wet gangrene requires emergent surgical consultation. Underlying vascular pathology must be evaluated by arteriography and corrected surgically or endovascularly. Patients with systemic toxicity should be resuscitated aggressively.

Obtain radiographs to help rule out clostridial myonecrosis (gas gangrene, see related item) and osteomyelitis.

Aggressive surgical debridement is necessary for cure in most cases of wet gangrene.

GAS GANGRENE (MYONECROSIS)

This infection causes rapid necrosis and liquefaction of fascia, muscle, and tendon. Most involve Clostridium perfringens; Streptococcus pyogenes accounts for the majority of remaining cases. Myonecrosis is classically associated with trauma (including surgery) and diabetes. There is edematous bronze or purple discoloration, flaccid bullae with watery brown nonpurulent fluid, and a foul odor. The classic clinical presentation is pain out of proportion to physical findings. Low-grade fever and other systemic signs are also typically present, and may develop rapidly into shock.

Crepitance and appearance of gross pockets of air in the tissue are appreciated, but may not be present early. The incubation period for clostridia ranges between 1 and 4 days, but it can be as early as 6 hours. Decreased tissue oxygen tension along with wound contamination is required for the infection to progress. Crepitant cellulitis, synergistic necrotizing cellulitis, acute streptococcal hemolytic gangrene, and streptococcal myositis are some conditions that may be mistaken for clostridial myositis. Often, surgical exploration of the fascia and muscle is required to make the correct diagnosis.

Aggressive resuscitation should be initiated, and consideration given to packed red blood cell transfusion. Broad-spectrum antibiotics, especially clindamycin, in conjunction with penicillin G, are given urgently. Tetanus prophylaxis must not be overlooked. Surgical debridement or amputation is the mainstay of therapy. Hyperbaric oxygen may have a synergistic effect in preventing the progression of infection and toxin production.

Shock and multiorgan failure may be rapidly progressive. Mortality is 80% to 90% if untreated, 10% to 25% when treated appropriately.

Clindamycin may improve survival by inhibiting toxin production.

Gram stain of gram-positive bacilli with a relative lack of leukocytes may rapidly confirm suspected clostridial myonecrosis.

FIGURE 12.8

Gas Gangrene. Radiograph of the foot in Fig. 12.7 exhibiting pockets of soft tissue gas tracking up the dorsal surface. (Photo contributor: Douglas Nilson, MD.)

NECROTIZING FASCIITIS

This uncommon, severe infection involves the subcutaneous soft tissues, including the superficial and deep fascial layers, with early skin sparing and late muscle involvement. It is most commonly seen in the lower extremities, abdominal wall, and perianal and groin area, as well as in postoperative wounds. It is commonly spread from a trauma site, surgical wound, abscess, or decubitus ulcer. Alcoholism, parenteral drug abuse, and diabetes are predisposing factors. Pain, tenderness, erythema, swelling, warmth, shiny skin, lymphangitis, and lymphadenitis are early findings. Later, there is rapid progression of bullae with clear pink or purple fluid and cutaneous necrosis. The skin becomes anesthetic, and subcutaneous gas may be present. Systemic toxicity may be manifest by fever, dehydration, leukocytosis, and frequently positive blood cultures. Type I includes anaerobic species (Bacteroides and Peptostreptococcus) and type II includes either group A streptococci alone or group A streptococci with S aureus.

Prompt diagnosis is critical; if made within 4 days from symptom onset, the mortality rate is reduced from ~50% to 12%. Initial treatment involves resuscitation with volume expansion, operative debridement, and prompt initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Intravenous calcium may be necessary to reverse hypocalcemia from subcutaneous fat necrosis.

Radiographs may detect nonpalpable subcutaneous gas.

Hemolysis and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) may be present.

Community-acquired MRSA has been implicated as a causative organism.

FIGURE 12.10

Necrotizing Fasciitis. Radiograph of the forearm in Fig. 12.9 showing extensive subcutaneous gas. (Photo contributor: Alexis Lawrence, MD.)

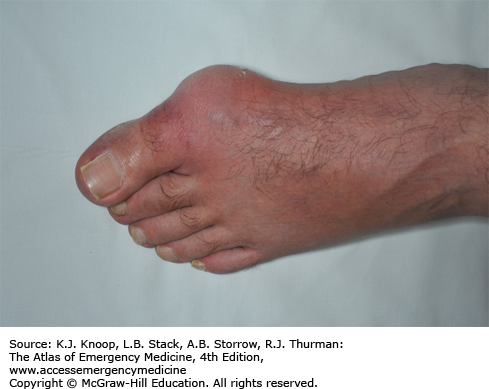

CRYSTAL-INDUCED SYNOVITIS (GOUT AND PSEUDOGOUT)

Gout is an inflammatory disease characterized by deposition of sodium urate monohydrate crystals in cartilage, subchondral bone, and periarticular structures. An acute attack is characterized by sudden onset of monoarticular arthritis (commonly in the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe) with swelling, erythema, and tenderness. The deposits of crystals about the joint produce a chronic inflammatory response termed a tophus.

In pseudogout, calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (rod- or rhombus-shaped, weakly birefringent) crystals are deposited. Although any joint may be involved, knees and wrists are most common. Presenting signs and symptoms are identical with gout, but formation of tophi is not seen. Low-grade fever, pain, and erythema are common to both entities.

Cellulitis and septic arthritis must be excluded. In the synovial fluid cell count, white blood cell count of 2000 to 50,000 with PMN predominance is expected (Table 1), although it may be significantly higher. The diagnosis is confirmed with urate or calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals on polarized microscopy (see Microscopic chapter) coupled with negative Gram stain and cultures.

| Normal | Septic Arthritis | Gout | Pseudogout | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Clear | Purulent, turbid | Turbid | Turbid |

| WBC | <200 | Usually >50,000 | 2000-50,000 | 2000-50,000 |

| PMN | <25% | >75% | >50% | >50% |

| Special Tests/Crystals | Normal “string sign” | + Gram stain, culture positive | Negative birefringence, needle crystals | Positive birefringence, rhomboid crystals |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories are used with excellent results acutely, along with joint immobilization and rest. Oral or intravenous (IV) colchicine is an alternative, but can cause nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as serious toxicities, including bone marrow suppression, neuropathy, myopathy, and death (particularly when given IV). Systemic and intra-articular corticosteroids and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) are alternatives. Allopurinol or probenecid is used in the chronic management of gout and plays no role in acute treatment.

Serum urate may be normal in acute gout.

Acute attacks may be triggered by minor trauma, diuretic or salicylate use, alcohol, or diet.

Punched-out subchondral bone lesions may be seen on radiography in chronic tophaceous gout. Chondrocalcinosis may be seen in pseudogout.

Synovial fluid cell counts alone cannot be used to differentiate crystalline arthropathies from infectious etiologies.

INGROWN TOENAIL (ONYCHOCRYPTOSIS)

This condition is the result of impingement and puncture of the medial or lateral nail fold epithelium by the nail plate, allowing growth into the dermis. Tenderness and swelling of the nail fold is followed by granulation tissue causing sharp pain, erythema, and further swelling. If not promptly treated, the granulation tissue becomes epithelialized, preventing elevation of the nail above the medial or lateral nail groove. Often, there is secondary bacterial or fungal infection. Risk factors include cutting the nail too short, tightly fitting shoes, and trauma. The differential diagnosis includes paronychia, felon, and tumor.

Early treatment: Elevation of the nail out of fold and placement of gauze under it to prevent contact, in conjunction with warm soaks, is the initial therapy.

Late treatment: Surgical management involves removal of part of the nail and the inflamed tissue, and sometimes destruction of the involved nail matrix. The lateral nail is removed followed by packing of the paronychial fold with petroleum gauze or other nonadherent dressing. Follow-up by a podiatrist until growth of the nail plate is complete should be considered. The destruction of the nail matrix is required only in patients with recurrent infected ingrown toenails and is not part of routine emergency care.

Ingrown toenail is most common in the great toe.

Use of antibiotics is not a substitute for surgical excision and will result in only transient improvement of symptoms.

LYMPHANGITIS

Inflammation of lymphatic channels in the subcutaneous tissues is commonly caused by spread of local bacterial infection; Group A β-hemolytic streptococcal species are the most frequently implicated. Lymphangitis is characterized by red linear streaks extending, within 24 to 48 hours, from a primary site of infection (eg, abscess, cellulitis) to regional lymph nodes (eg, axilla, groin). The lymph nodes are often enlarged and tender. The differential diagnosis includes cellulitis, trauma, and superficial thrombophlebitis.

Rest, elevation, immobilization, and antibiotics are the initial treatment. Coverage for Streptococcus and Staphylococcus is appropriate. Toxic-appearing patients require admission for parenteral antibiotics. Any patient sent home with oral antibiotics should be followed up in 24 to 48 hours. Patients who subsequently do not show improvement require admission for parenteral antibiotic therapy. Consider treatment for CA-MRSA in addition to standard skin coverage in highly endemic areas.

Consider Pasteurella multocida with cat and dog bites, Spirillum minus with rat bites, and Mycobacterium marinum in association with swimming pools and aquaria.

Chronic lymphangitis may be associated with mycotic, mycobacterial, and filarial infection.

Aspiration of the leading edge is generally not helpful for acute management.

FIGURE 12.18

Lymphangitis. Severe lymphangitis extending from metacarpophalangeal wound up the arm from a “fight bite.” The red streak extends from the hand to the axilla, extending along lymphatic channels. (Photo contributor: Selim Suner, MD, MS.)