INTRODUCTION

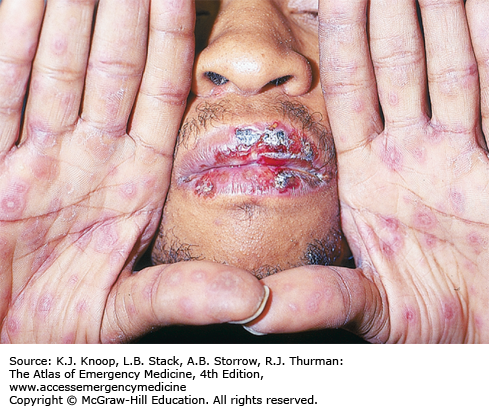

STEVENS-JOHNSON SYNDROME/TOXIC EPIDERMAL NECROLYSIS

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are two ends of a continuum of life-threatening, reactive diseases. Generally, SJS involves epidermal detachment of less than 10% body surface area (BSA) and TEN greater than 30%; TEN and SJS overlap between 10% and 30%. Two or more mucosal sites are usually affected. The overall mortality of SJS is 1% to 5%, while that of TEN approaches 30%.

SJS/TEN begins with a nonspecific prodrome of upper respiratory tract symptoms, fever, fatigue, myalgia, headache, and mucous membrane and skin sensitivities. A rash appears 1 to 3 days later with mucosal lesions first (erythema, erosions, and hemorrhagic crusting) and a simultaneous or lagging, generalized, dusky, erythematous rash. Bullae form, large sheets of epidermis separate from the dermis, and the involved skin is exquisitely tender to palpation. The Nikolsky sign is present when lateral pressure on unblistered skin causes the epidermis to slide off. Progression of involved skin can occur over a single day or slowly evolve over 14 days. In addition to the generalized “skin failure,” life-threatening sepsis, respiratory failure, metabolic derangements, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage may occur. These serious complications may be compounded by underlying comorbidities.

With a few exceptions, SJS/TEN results from a drug exposure, generally within 7 to 21 days previous to the prodrome. Sulfonamide antibiotics, aromatic anticonvulsants (phenytoin, phenobarbital, and carbamazepine), penicillins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), allopurinol, lamotrigine, and antiretrovirals are common causes, although over 200 medications, including over-the-counter (pseudoephedrine) and herbal remedies, have been implicated. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and vaccinations have also been associated with SJS/TEN.

Stop the offending medication (sometimes requiring withholding all). Assess airway status and secure admission to a burn intensive care unit. SJS/TEN patients require careful attention to fluid management; burn protocols may overestimate fluid requirements and contribute to pulmonary edema (resuscitation should maintain urine output at ~0.5-1 mL/kg/h). Dress denuded skin with gauze bandage rolls and moisten with normal saline (transition to antibacterial solution in the burn unit). Emergently consult dermatology and ophthalmology. Meticulous supportive care is the foundation of treatment. With dermatology and burn unit consultation, consider intravenous immune globulins (IVIg) within 72 hours.

The only intervention proven to decrease mortality is to stop the offending medication.

If a patient notes continued skin pain, even in areas of normal skin, expect additional sloughing.

High-risk groups to develop TEN include cancer/hematologic malignancies, HIV/AIDS, immunosuppression, slow acetylator genotypes, anticonvulsant use associated with radiotherapy, and specific human leukocyte antigen alleles (HLA-B*1502 associated with carbamazepine and HLA-B*5801 associated with allopurinol).

Infections and pulmonary edema/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are the leading causes of death in TEN patients.

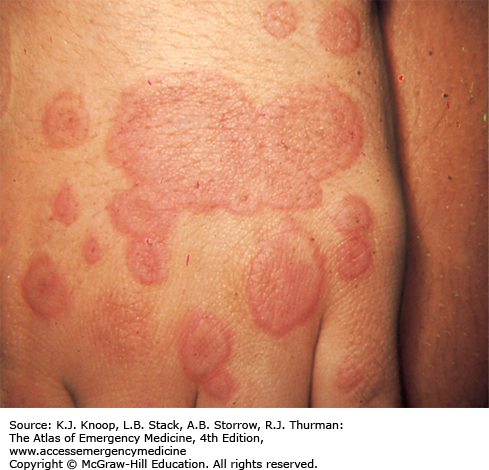

ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME

Erythema multiforme (EM) begins with symmetric, erythematous, sharply defined extremity or trunk macules, and evolves into a “targetoid” or “bull’s eye” morphology (a flat, dusky, central area with two concentric, erythematous rings). Bullae may appear in the central dusky area (bullous EM). The mucous membranes, typically oral, may become involved and raise concern for SJS. The typical targetoid lesions allow a diagnosis to be made clinically (bullae, purpura, and mucosal involvement should prompt a dermatology consultation). The rash usually persists for 1 to 4 weeks.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV; frequently labialis) is strongly associated but may not be clinically apparent. Other viruses, bacteria (M pneumoniae, Chlamydia, Salmonella, Mycobacterium), and fungi (Histoplasma capsulatum, dermatophytes) are also associated. Medications account for <10%; NSAIDs, sulfonamides, antiepileptics, allopurinol, and antibiotics are responsible for the majority. Physical factors such as trauma, ultraviolet light exposure, and cold have been reported to elicit EM.

Prevention of HSV recurrences is essential. Antivirals administered after lesions present have minimal clinical impact, but patients should be referred for future prophylaxis consideration. Use of facial sunscreens and lip balms may help prevent UVB-induced recurrences. Systemic steroids are discouraged but can be considered in atypical presentations. With the distinctive clinical findings and no systemic symptoms, patients may be discharged home. Systemic symptoms and atypical presentations require admission and dermatologic consultation.

EM does not progress to TEN.

Reassure patients that the lesions will completely resolve without scarring. Hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation may occur but should resolve over months.

Eye involvement requires a slit-lamp examination and ophthalmologic consultation to exclude active HSV infection.

Patients with immunosuppression are more prone to recurrent and prolonged episodes.

The dusky centers help differentiate EM from typical exanthematous drug reactions (no dusky centers) and urticaria (normal central zone skin).

FIGURE 13.5

Erythema Multiforme. Wrist, hand, and fingers with typical central dusky centers surrounded by the concentric “bull’s eye” rings. (Reproduced with permission from Weinberg S, Prose NS, Kristal L. Color Atlas of Pediatric Dermatology. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008: Fig. 13-9.)

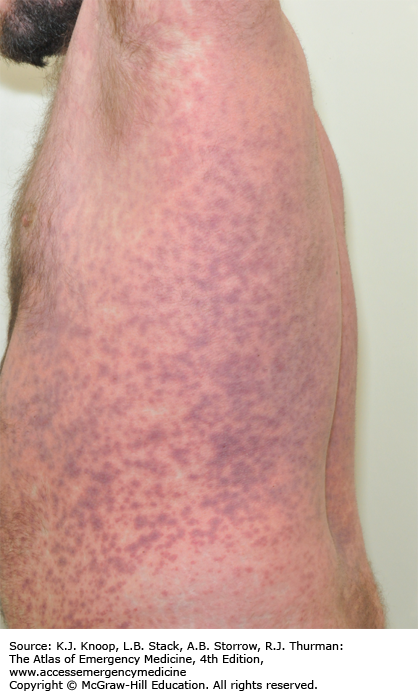

DRUG ERUPTIONS

Exanthematous drug eruptions present 7 to 14 days after a new medication but may appear sooner with rechallenge. A symmetric, erythematous, morbilliform, blanching, eruption is most frequently encountered. Typically, pruritus and low-grade fever are present. The macules and papules usually become confluent and may progress to an exfoliative dermatitis (rarely to erythroderma). The eruption peaks in a few days and, if the culprit medication is stopped, completely resolves over 7 to 14 days.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), a type of drug eruption, presents 1 to 5 days after starting a new medication (typically, a β-lactam or a macrolide antibiotic). A high fever is usually noted with neutrophilia (90% of patients) and eosinophilia (30%). The rash begins on the face and intertriginous areas with edematous erythema studded with nonfollicular, <5 mm pustules. Within hours, it becomes generalized with larger flaccid, flat pustules. Over the next 2 to 4 days, widespread superficial desquamation occurs. Mucosal sites, especially oral mucosa, can be involved. With the cessation of the offending medication, the rash slowly resolves over 2 weeks.

While exanthematous drug eruptions may resolve despite the medication’s continued use, cessation of the causative agent is paramount. Symptomatic management includes antihistamines and topical corticosteroids.

The appearance of AGEP, with pustules, fever, and neutrophilia, is difficult to distinguish from an infectious etiology. Wound and blood cultures should be obtained early. Consult dermatology to help differentiate from pustular psoriasis, cellulitis, EM, bullous diseases, SJS, and TEN. Treatment consists of supportive care. The large surface area of desquamation makes secondary infection a major concern.

Exanthematous drug eruptions are usually symmetric and pruritic as opposed to viral eruptions, which are usually asymmetric and asymptomatic.

Mononucleosis patients taking amoxicillin or AIDS patients taking sulfa drugs frequently experience this reaction (augmented by viral infections).

The desquamation seen in AGEP is much more superficial than the full-thickness desquamation seen in SJS or TEN.

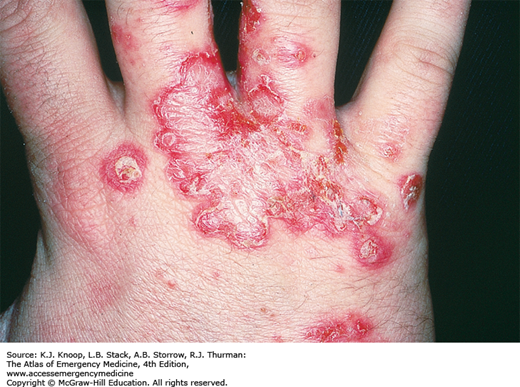

FIGURE 13.9

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis. Note the large, flaccid pustule (sterile) and surrounding smaller pustules. The smaller pustules are typical of the initial AGEP presentation. These will eventually slough off and leave a superficial, erythematous erosion. (Photo contributor: J. Matthew Hardin, MD.)

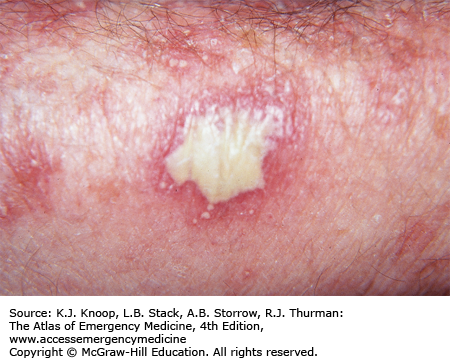

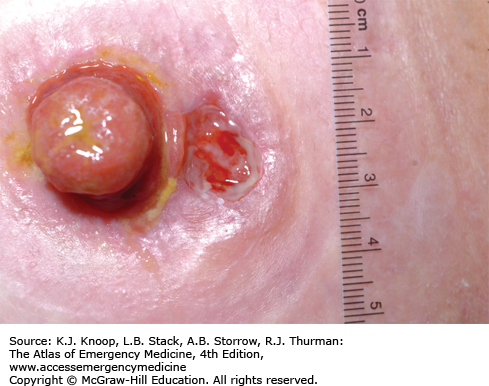

FIXED DRUG ERUPTION

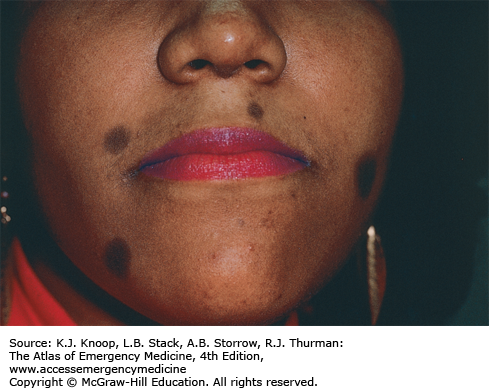

Fixed drug eruptions (FDEs) appear 7 to 14 days after first exposure. The lesions can appear anywhere, including mucous membranes, but are most common on the face, lips, hands, feet, and genitalia. Single or multiple annular, edematous, well-demarcated plaques are typical. A central vesicle, bulla, or erosion may occur. After stopping the offending medication, the lesion(s) fade over several days. Residual hyperpigmentation is common. Within 24 hours of reexposure to the culprit medication, the exact rash reappears. The most common offending medications are sulfonamides, NSAIDs, barbiturates, tetracyclines, and carbamazepine.

Identify all potential medications (prescription, herbal, and over-the-counter) and stop the offending drug. Symptomatic treatment with antihistamines and analgesics is sufficient. Refer to dermatology for further evaluation.

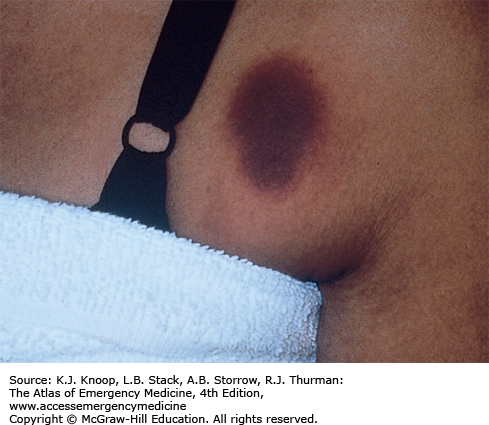

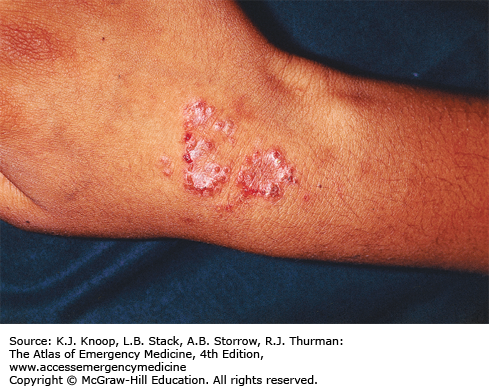

FIGURE 13.10

Fixed Drug Eruption. This red to violaceous, pruritic, sharply demarcated patch is a cutaneous reaction to a drug. Repeated exposure will cause a similar reaction in the same location. (Photo contributor: Department of Dermatology, Wilford Hall USAF Medical Center and Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, TX.)

Without a thorough history including medication use, FDEs are difficult to identify.

Pseudoephedrine, a common over-the-counter medication, is a frequent cause of FDEs.

Warn patients that hyperpigmentation is expected and may not completely resolve.

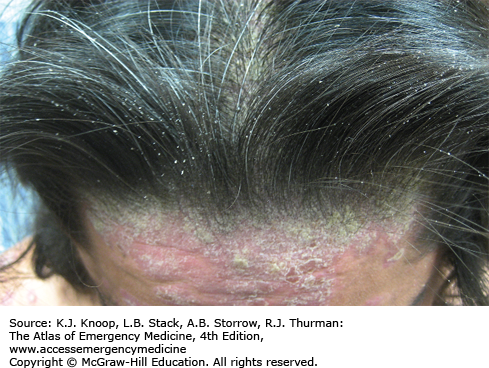

DISSECTING CELLULITIS OF THE SCALP

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp occurs predominately in young black males. This condition, along with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), and pilonidal cysts, is the “follicular occlusion tetrad.” Multiple, fluctuant abscesses on the scalp vertex and occiput are present. Sinus tracts form between the abscesses and purulent; foul-smelling discharge may be present. Over time, extensive scarring alopecia can result.

Exclusion of a secondary infection is paramount. Incision and drainage of new, rapidly forming abscesses may be helpful; obtain cultures if this is attempted. Antibiotics help prevent further abscesses; the tetracyclines help decrease the inflammatory component. Since this is an inflammatory condition, antibiotics alone are not adequate. Refer the patient to a dermatologist for biopsy and further treatment.

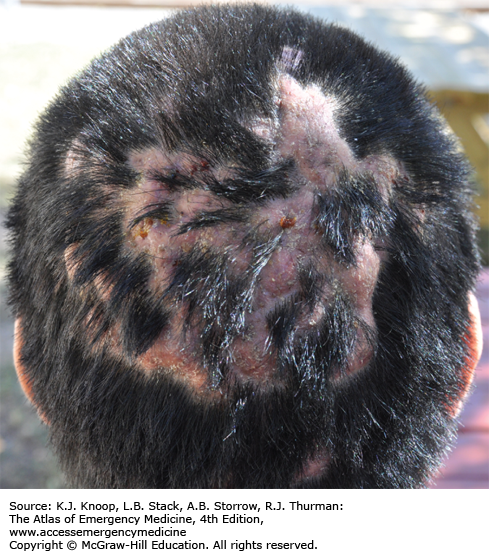

FIGURE 13.13

Dissecting Cellulitis of the Scalp. Many active sinus tracts and alopecia in a young Hispanic man. (Photo contributor: Richard P. Usatine, MD. Used with permission. From Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley HS. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; 2013: Fig. 189-7.)

Consider this diagnosis when presented with recurrent scalp abscesses and draining sinus tracts unresponsive to antibiotics.

Early diagnosis and referral can prevent further scarring and alopecia.

Most patients are young males; the psychological impact can be significant.

HIDRADENITIS SUPPURATIVA

HS most commonly affects obese, postpubertal females. This unremitting disease involves hair-bearing intertriginous sites such as the axillae, inguinal folds, gluteal fold, perianal area, and inframammary folds. Individual lesions begin with erythematous nodules that become tender and fluctuant. The sterile abscess ruptures with a suppurative discharge and eventual sinus tract formation or fistulae. This is a primary inflammatory response to the follicle and is not infectious; however, secondary infections are common. Severe hypertrophic scar formation may be dramatic and disfiguring. In addition, chronic discharge is difficult to control and may become malodorous. The differential diagnosis includes bacterial furunculosis, granuloma inguinale, mycetoma, tuberculosis, and fistulas associated with inflammatory bowel disease.

HS should be identified and local or systemic infection ruled out. Topical and systemic antibiotics help improve lesions, especially if a secondary infection is suspected. Oral doxycycline or minocycline, with topical clindamycin, is common first-line agents. If possible, incision and drainage should be avoided as this can induce chronic sinus tract formation and worse scarring. Referral to a dermatologist for chronic management and alternative treatments is indicated.

HS is not a primary infectious process but rather inflammatory. This often leads to delayed diagnosis, worse skin involvement, and permanent scarring.

One hallmark of hidradenitis is the “double comedones,” a blackhead with two or greater surface openings with superficial communication.

Perianal involvement should prompt gastroenterology referral to rule out inflammatory bowel disease.

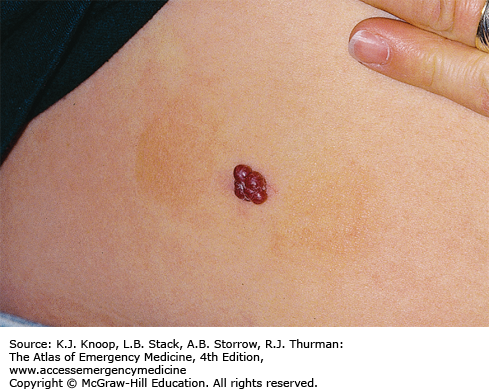

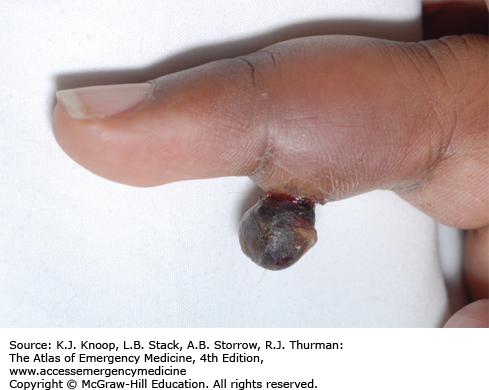

PYOGENIC GRANULOMA

Pyogenic granuloma presents as an eruptive, friable papule over weeks. They are frequently located on the extremities, face, or at trauma sites. Children are most commonly affected but they can occur at any age. The lesion will bleed with very little trauma. If the papule is not completely removed, it will likely recur at the same site. Pregnant women have a higher incidence of pyogenic granulomas (common on the gingiva).

Most emergency department (ED) presentations of pyogenic granuloma will be due to prolonged, often brisk, bleeding. Silver nitrate applied to the papule base is usually effective (avoid on the face to prevent permanent staining). Refer patients to a dermatologist for possible biopsy and definitive treatment.

An association with isotretinoin, indinavir, epidermal growth factor receptor agents, and capecitabine has been described.

Approximately one-third of these benign lesions follow some form of minor trauma.

Refer patients for biopsy and histology to exclude other vascular tumors.

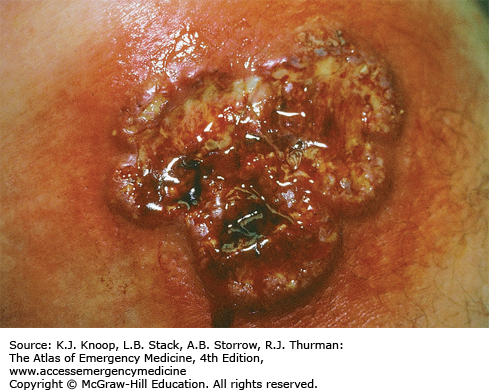

PYODERMA GANGRENOSUM

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is an inflammatory condition of all ages but is most common among 20- to 50-year-old females. Lesions can be located anywhere (most commonly on the lower extremities) and begin as a papulopustule surrounded by erythema. This pustule erodes to form a necrotic ulcer. Similar satellite pustules and ulcers form around the original lesion and eventually coalesce into a large ulcer. The surrounding border is “rolled,” due to the convex elevation, and has a violaceous hue. The ulcers are exquisitely tender to movement and palpation. On the extremities, the ulcers can rapidly involve muscles and tendons. Ostomy sites are a common location and make care very difficult.

Half of cases are idiopathic; the other half are associated with inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic diseases (leukemia, myelodysplasia, monoclonal gammopathy), and the arthritides. Since diagnosis is based on examination, dermatopathology, and exclusion of other causes, it is difficult to confirm and delayed treatment is common. The most concerning diagnosis to exclude is infection due to bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, syphilis, or amebiasis. Loxosceles spider bites and large vessel vasculitis are also considerations.

Appropriate cultures should be obtained. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are indicated for secondary infections. Consult dermatology for biopsy, tissue culture, and initiation of immunosuppressant therapy.

With the number of ulcers seen in the ED, early diagnosis of PG is difficult and requires a high level of suspicion.

PG is often not diagnosed until late-stage ulcer formation and after multiple failed skin grafts. Without immunosuppressant therapy, skin grafting is unlikely to succeed.

Half of PG cases have associated diseases; each case needs a thorough specialty evaluation.

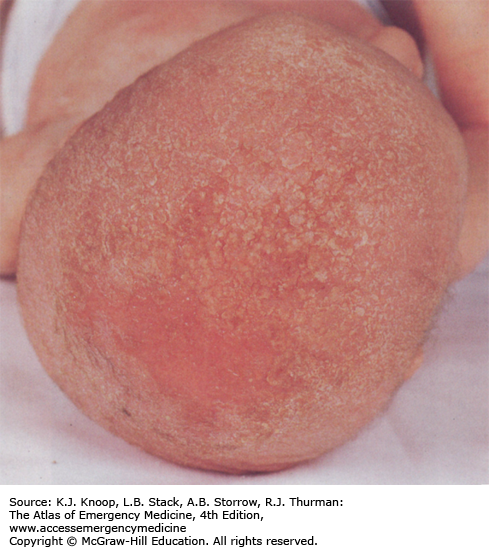

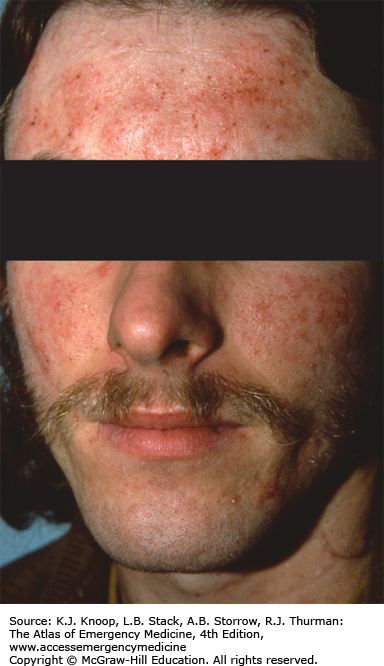

SEBORRHEIC DERMATITIS

Seborrheic dermatitis represents a spectrum ranging from localized lesions to generalized exfoliative erythroderma. All ages are affected. Lesions have an erythematous base with a yellow, greasy scale. The scalp, external auditory canal, postauricular, eyebrows, eyelids, face (especially the nasolabial folds), axillae, umbilicus, presternal chest, and groin are common locations. Infants can have lesions at the above sites, but focal and confluent lesions are most common on the scalp and called “cradle cap.”

Seborrheic dermatitis is a lifelong disease and has no cure; management is directed at control. Localized cases are effectively treated with topical 2% ketoconazole. Scalp involvement can be treated with selenium sulfide, ketoconazole, or zinc pyrithione shampoos. Parents of affected infants should be reassured that infantile seborrheic dermatitis is self-limited. Refer to a dermatologist for confirmation of diagnosis and chronic care.

New-onset, severe, or prolonged seborrheic dermatitis may indicate a new HIV infection or immunosuppression.

Although there is no cure, reassure adult patients that the rash can be well controlled with topical medications.

In infants, seborrheic dermatitis can appear indistinguishable from Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Always have a clear discharge plan to follow up with a pediatrician or dermatologist.

FIGURE 13.24

Seborrheic Dermatitis. Erythema and yellow-orange scales and crust on the scalp of an infant (“cradle cap”). Eczematous lesions are also present on the arms and trunk. (Used with permission from Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005: 51.)

PSORIASIS

Psoriasis has many forms. The most common is chronic plaque psoriasis with stable, symmetric lesions on the trunk and extremities, especially the elbows and knees. Lesions are well-defined, erythematous plaques with silvery scales. Inverse psoriasis represents a form that involves the intertriginous areas and, due to the moist environment, the silvery scale is absent. Guttate psoriasis, common in children and young adults, presents with an abrupt eruption of 2- to 5-mm erythematous scaly papules on the trunk and extremities. A preceding respiratory infection, usually streptococcal pharyngitis, can be a precipitant. Pustular forms of psoriasis can present as localized (nail bed, finger, palms, or soles) or generalized. It is characterized by erythema and “lakes of pus.” Triggers for pustular psoriasis include steroid withdrawal (as in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] and asthma exacerbations), pregnancy, infections, and topical irritants.

ED management should ensure there is no infectious etiology or systemic symptoms. Localized psoriasis typically responds to topical glucocorticoids, although the chronicity and variety of other management options, including phototherapy, should prompt referral to dermatology. Pustular forms may be challenging and require admission. Guttate psoriasis may respond to antistreptococcal antibiotics. Obtain emergent consultation with a dermatologist for patients with generalized presentations and referrals for localized disease.

Medication-induced psoriasis is associated with β-blockers, lithium, interferon, and antimalarials.

Patients with psoriasis have a higher incidence of coronary artery disease, obesity, tobacco use, and alcoholism.

PITYRIASIS ROSEA

The first sign of pityriasis rosea (PR) is usually a well-demarcated, salmon-colored macule that evolves into a larger patch (1-4 cm) with peripheral scaling (“herald patch”). Over 1 to 2 weeks, generalized, bilateral, and symmetric macules and plaques appear along cleavage lines. The macules have a peripheral collarette of fine scaling (termed “Christmas tree” pattern). Most patients will have severe itching associated with the generalized eruption. The lesions slowly resolve over 6 to 8 weeks. Atypical presentations in children include inverse PR (presentation on the face, axillae, and/or inguinal areas) and papular PR (peripheral scaling papules with central, hyperpigmented plaques). A viral etiology is postulated due to seasonal variation and case clustering.

PR is both benign and self-limited. Pruritus can be treated with oral antihistamines, topical steroids, and oatmeal baths.

Patients often will not describe the herald patch unless specifically asked.

In patients with risk factors for syphilis and HIV, appropriate screening tests should be performed.

Patients should be warned of the possible extended course of PR and given appropriate antihistamines and follow-up.

Atypical presentations are seen in dark-skinned individuals.

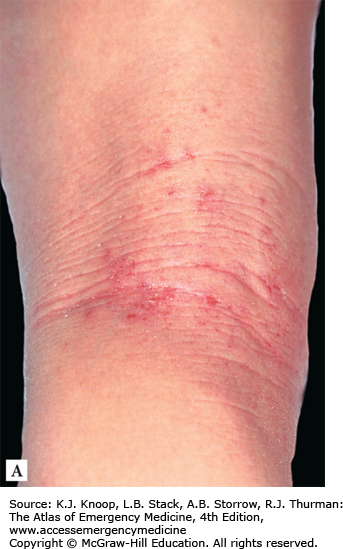

ATOPIC DERMATITIS

Atopic dermatitis presents in three overlapping stages: infantile, childhood, and adult. Infantile begins after 2 months of age and is symmetrically distributed on the cheeks, scalp, neck, forehead, and extensor surfaces of the extremities. The lesions begin as erythema or papules, but, with persistent itching and rubbing, they become thin plaques, exudative and crusted. Childhood atopic dermatitis presents with flexural involvement. Other areas frequently involved are the face, neck, and trunk. The scratching induces plaque lichenification and potential for secondary infection. Adult atopic dermatitis is less specific but can present with a childhood-like distribution, papular lesions that coalesce into plaques, and chronic hand dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis can become a generalized exfoliative erythroderma. Differential diagnoses include seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, irritant or allergic contact dermatitis, nummular eczema, and scabies.

If a severe flare, suprainfection, punched-out lesions (eczema herpeticum), or a generalized exfoliative erythroderma is present, an ED dermatologic consultation is indicated. Mild cases can be sent home with referral. Patients (caregivers) should avoid soaps, detergents, or any personal products with fragrances. After bathing, pat dry the skin and smear a thin film of petrolatum or mild corticosteroid over the affected areas. Wearing damp pajamas (100% prewashed cotton) after application of emollients/mild corticosteroids can help rapidly heal the skin.

Atopic dermatitis is often called the “itch that rashes” since pruritus precedes clinical disease.

If dispensing corticosteroids, use appropriate classes for the affected site and patient age. In addition, specific instructions should be written for the patient.

Frequent relapses are common and require an astute clinician to differentiate associated complications.

FIGURE 13.35

Atopic Dermatitis. A typical localization of atopic dermatitis in children is the region around the mouth, with lichenification and fissuring and crusting. (Used with permission from Wolff K, Johnson RA, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2013: Fig. 2-14.)

FIGURE 13.36

Atopic Dermatitis. (A) One of the hallmarks of atopic dermatitis is lichenification in the flexural regions. Note the thickening of the skin with exaggerated skin lines and erosions. (B) Atopic dermatitis in black child. Pruritic follicular papules on posterior leg. Follicular eczema pattern is more common in African and Asian children. (Used with permission from Wolff K, Johnson RA, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2013: Fig. 2-15 A and B.)

NUMMULAR/XEROTIC ECZEMA

Nummular eczema is characterized by an erythematous, edematous, vesicular, and crusted extremity plaque. The lesions enlarge by forming satellite, peripheral papulovesicles that coalesce with the original lesion. Pruritus is the dominant symptom.

Xerotic eczema (also called winter itch, eczema craquele, and asteatotic eczema) presents on the anterior shins, extensor arms, and flanks. The lesions are erythematous patches with fine, cracked fissures and adherent scaling. The edema and exudate present in nummular eczema is absent. Pruritus can be severe. This is a common finding in the winter and in the elderly.

Treatment of nummular eczema consists of mid- to high-potency topical steroids under occlusion. Prevention of secondary infection is important as patients frequently cannot resist scratching.

Xerotic eczema is treated with topical emollients (petrolatum), three to four applications per day. Topical steroids may be required for areas with inflammation.

Nummular eczema should be considered with lesions unresponsive to antibiotics and pruritus as the dominant feature.

Both of these entities are associated with significant pruritus and secondary infections, especially in the young and elderly.

FIGURE 13.39

Eczema. Nummular eczema on the extensor surface of the forearms and elbows. Thickened, scaly lesions resemble psoriatic plaques. A biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of nummular eczema. (Photo contributor: Richard P. Usatine, MD. Used with permission. From Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley HS. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; 2013: Fig. 148-6.)

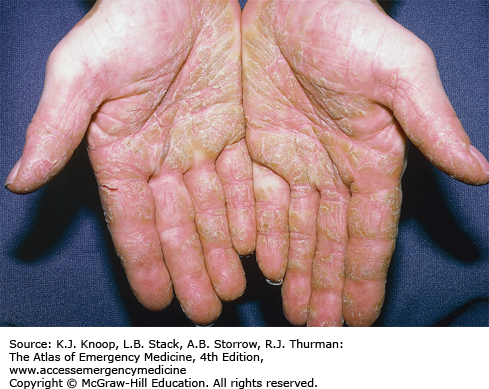

DYSHIDROTIC ECZEMA

Dyshidrotic eczema (also called pompholyx or acute vesiculobullous hand eczema) is the abrupt appearance of deep-seated, 1- to 2-mm vesicles on the sides of the fingers, palms, and soles. The vesicles are extremely pruritic, may coalesce into larger bullae, and may rupture to become dry or fissured. The outbreak usually resolves over a few weeks unless secondary infection develops. The differential includes bullous tinea, id reaction, scabies infestation, or allergic contact dermatitis.

Treatment includes a high-potency topical steroid and prevention of secondary infection. Refer to a dermatologist for long-term treatment; this is often a chronic condition with significant disability.

The initial lesions resemble tapioca pudding.

These lesions wax and wane and are often exacerbated by stressful events.

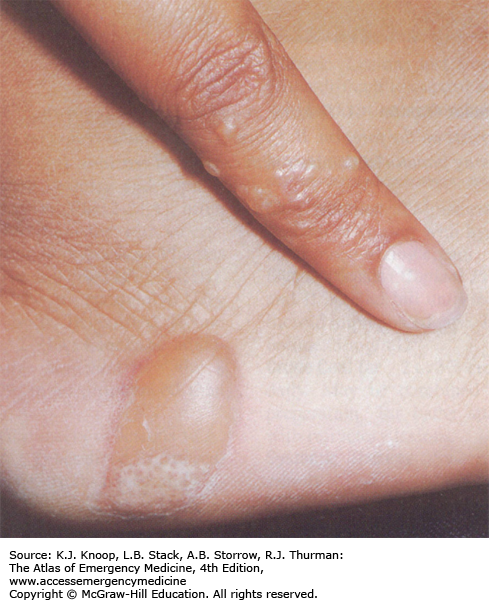

FIGURE 13.40

Dyshidrotic Eczema. In most cases dyshidrotic eczematous dermatitis starts with tapioca-like vesicles on the lateral aspects of the fingers. (Photo contributor: Richard P. Usatine, MD. Used with permission. From Usatine RP, Smith MA, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley HS. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill; 2013: Fig. 147-7.)

FIGURE 13.41

Dyshidrotic Eczema. The vesicles show confluence and spread to the palm but also to the wrist and dorsal aspect of the hand when the eruption progresses. (Used with permission from Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas & Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005:45.)

ID REACTION (DISSEMINATED ECZEMA)

Id reactions are seen in response to a variety of disorders, including fungal infection (tinea capitis and tinea pedis), scabies infestation, pediculosis capitus, molluscum contagiosum, bacterial and mycobacterial infections, and arthropod bites. The rash appears days to weeks after the instigating rash and consists of erythematous papules (sometimes crusted at the apices) as well as eczematous patches and plaques. The rash can be local to the instigating lesions/rash, distant, or generalized. The id reaction usually presents on the extremities, commonly on the sides of fingers, but may occur on the face and trunk. Pruritus is intense. The id reaction will not demonstrate infectious organisms and may not respond to topical steroids.

Recognition and treatment of the initial infection or infestation is curative. Refer to a dermatologist for follow-up to ensure diagnosis and resolution.

Repeated ED evaluation for fungal infection or eczematous rash should prompt further investigation for a distant, untreated, or occult fungal infection.

Id reactions are intensely pruritic; make sure secondary bacterial infections do not develop from excoriations.

Recurrences are common, especially if the primary source is not treated adequately.

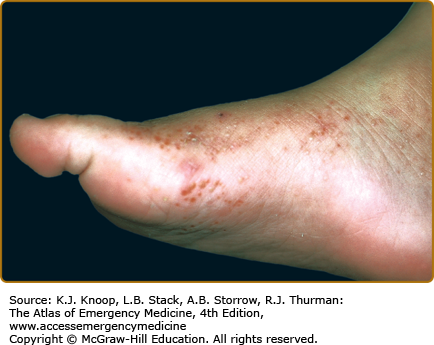

FIGURE 13.43

Id Reaction. Id reaction to tinea pedis. Erythematous, partially dried up, pruritic vesicles on the foot. (Used with permission from Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, Wolff K. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2012: Fig. 16-7.)

STASIS DERMATITIS

Stasis dermatitis results from venous insufficiency, is characteristically distributed on the distal tibia above the medial malleolus, and appears early with erythematous patches. These can progress to scaling as well as eczematous and weeping plaques. Patients will often have light brown pigmentation distributed on the lower third of the extremity due to microvasculature blood extravasation (hemosiderin deposition secondary to increased superficial capillary pressure). Varicose veins are usually present, although they are often difficult to visualize in obese patients. Patients with heart failure, cirrhosis, and nephrotic syndrome are at increased risk due to a chronic edematous state.

Referral to a primary care physician should be initiated to address the underlying etiology (eg, valvular insufficiency, thromboembolic disease, chronic edematous state). Daily elevation of the extremities and compression hose use should be encouraged. Emollients and mid-potency topical steroids help decrease the pruritus and promote healing.

Differentiation of stasis dermatitis and early cellulitis can be extremely difficult. Clinical history and deviation from previous presentations may be helpful. Follow-up for reevaluation should be obtained.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree