| 1 | Basic Principles |

Orthopedic Pain Therapy

NOTE

Orthopedics is the medical specialism that concerns itself with the musculoskeletal system.

As such, it deals with the diseases and injuries found in bones, ligaments, muscles, and joints at every stage of life. Orthopedics is described more precisely in the official definition contained in the regulations governing the continuing education of orthopedic specialists:

“Orthopedics envelops the recognition, treatment, prevention, and rehabilitation of congenital and acquired changes in form and functional disorders, disease and injury of the musculoskeletal organs, as well as the pain therapy within these areas.”

The spectrum of orthopedic medicine ranges from malformations of the spine and limbs to inflammatory bone and joint diseases, pediatric orthopedics, orthopedic oncology, rehabilitative medicine, and technical orthopedics. It also includes injuries and damage to the musculoskeletal organs caused by wear and tear, as well as the pain states associated with these injuries.

The essential components of conservative orthopedics include not only the treatment of pain but also recovery from musculoskeletal disorders that affect function and form. This includes the use of bandaging, physical agents and electrotherapy, manual therapy, systemic pharmaceutical therapy, local injections, physiotherapy, and orthopedic devices.

NOTE

Pain can be defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience.

The International Association for the Study of Pain has agreed on a more extensive definition of pain: “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (IASP 1979).

This definition distinguishes pain from other unpleasant sensations by relating it to physical damage. The second part of the definition acknowledges that pain may be experienced even when no tissue damage can be demonstrated at that instant. This extension of the definition is especially important for pain that is described as chronic.

Further sensory disorders within the musculoskeletal system which possess possible warning functions include:

- hypoesthesia: reduced sensation to touch

- anesthesia: loss of sensation

- dysesthesia/paresthesia: abnormal sensations described as being like ants crawling, pins and needles, or a furry feeling

- hyperesthesia: increased sensitivity to touch stimuli

- hyperalgesia: hyperalgesia: increased sensitivity to pain.

These sensory disturbances occur in the musculoskeletal system with or without pain, e. g., with nerve root syndromes, peripheral nerve lesions, and in the area surrounding surgical wounds. Local numbness and sensory disorders often remain after a subsided nerve compression. They can function as an alarm, e. g., saddle anesthesia caused by cauda equina syndrome.

Acute and chronic pain are not differentiated solely by the duration of the pain. Acute pain in the musculoskeletal system is felt following acute events, e. g., stretching of the joint capsule, muscle tears, or disk prolapse.

NOTE

Acute pain begins suddenly, gives a warning, and elicits an immediate reaction. In most cases, this reaction involves adopting a relieving posture with an increase in muscle tension so as to combat the cause of the pain.

A chronic pain syndrome or pain cronification in the musculoskeletal system is described as pain that is constantly or intermittently present over a period of at least 3 months. The most common causes are relapsing spinal syndromes with or without radiation into the extremities. The progression from acute to chronic pain is described as chronification.

NOTE

Chronification acute pain → chronic pain.

Within the musculoskeletal system, the chronification of pain is defined as the transition from acute to chronic pain, where pain is present formore than 3 months and has lost its warning function. The patient exhibits an increase in secondary psychological symptoms, with a change in the perception and processing of pain signals. The relationship between the intensity of the pain stimuli (e. g., tissue damage) and the pain reaction is lost.

The degree of cronification is dependent on:

- the duration of pain

- pain dispersion

- response to medication

- the doctor–patient relationship

- changes in experience and behavior.

Example

Symptoms of lumboischialgia persist for several months during the chronification process. The radiating pain and the area of radiation into the leg change constantly. The patient requires stronger medication to deal with the pain, and ends up by changing doctors.

NOTE

We speak of a chronic pain syndrome when the perceived pain is largely independent of the original cause of pain and has become an independent disease state.

Concomitant symptoms, such as increasedmuscle tension, abnormal posture, and psychogenic reactions become more important. These symptoms may even become a disease in their own right, even when the cause of pain is no longer present.

Chronic pain syndrome is also referred to as “pain disease” (Adler et al. 1989, Eggle and Hoffmann 1993, etc.) to emphasize that it is the pain itself that has become a disease. One disadvantage of this terminology is that patients are given the impression that because they have a “disease” there is nothing they can do about the pain. It is exactly this interpretation that is detrimental in chronic pain syndrome. In fact, the opposite is true, and patients should be educated in how to actively control their pain.

An example of a chronic pain syndrome

The chronic irritation of a nerve root due to a disk prolapse or a lateral spinal canal stenosis. The symptoms often remain, even when the cause of pain has been removed (e. g., by surgery). The nervous system has learnt to perceive pain (see “Moving from Acute to Chronic Pain: Nociceptor Sensitization,” below).

Orthopedists use a variety of methods to treat pain. Aside from the administration of common analgesics in general pain therapy, other methods specifically related to orthopedics include:

- physical therapy

- physical agents and electrotherapy

- manual therapy

- local injections

- orthopedic technical aids

- movement programs

- surgery.

Following injury, therapy for orthopedic pain is applied directly or indirectly to the somatic source of pain, and should prevent the chronification of pain. The progression of acute pain to chronic pain and subsequently to a chronic pain syndrome should be halted right from the start. When the initial intervention is unsuccessful, or too late, treatment must increasingly take psychological aspects into consideration. Psychology and orthopedics are of equal importance in the treatment of chronic pain, chronic pain syndromes, and somatic psychogenic disorders. Purely psychogenic disorders primarily require the input of a psychologist. At the same time, orthopedic surgeons must rule out primary organic disorders and keep a look out for secondary functional disorders as required.

Nociception and Chronification

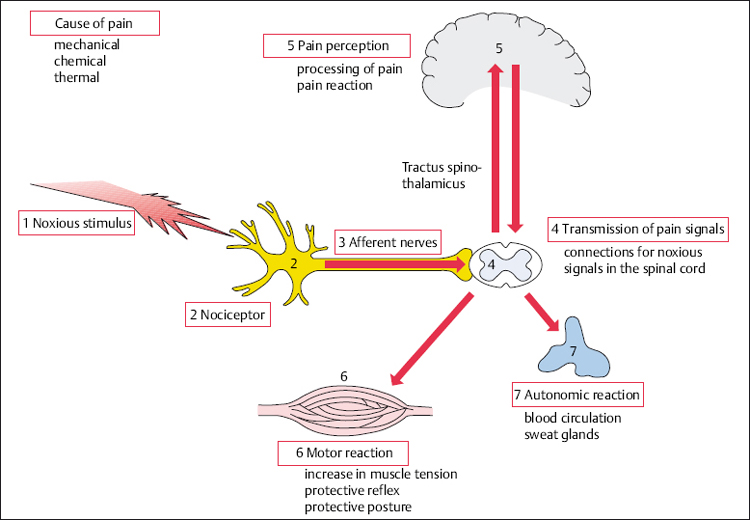

The pain process goes through several phases: from the activation of nociceptors and conduction of nociceptive impulses, to pain perception and muscular and autonomic reactions. The sequencing of painful events in the musculoskeletal system is specific. Musculoskeletal pain arises from mechanically inflammatory, thermal, or chemical stimuli that affect bones, muscles, tendons, and joint capsules. The pain caused by these noxious stimuli is perceived in the cerebrum. At the spinal level, pain stimuli are distributed for example to the muscular system and the autonomic nervous system.

The physiology of musculoskeletal nociception is based on the existence of an extensive, independent peripheral nervous system which is dedicated to the perception of peripheral musculoskeletal pain. The process shown in Fig. 1.1 occurs when a stimulus sufficient to cause pain irritates a nociceptive system which has not been previously damaged (by being sensitized, or by the development of chronic pain).

The noxious stimuli, nociceptors, and afferent fibers combine to form the pain-creating complex. Pain signals travel from the spinal cord into the cerebral cortex, the limbic system of the brain (which affects the emotions), the anterior horn of the spinal cord (which forms part of the musculoskeletal system), and the autonomic nervous system. A multitude of transmitters, modulators, and their corresponding receptors participate in nociceptive processes within the central nervous system (CNS) (Schmidt and Thews 1997).

Fig. 1.1 Nociception and processing of pain signals arising from bones, muscles, tendons, and joints. The transitional areas, e. g., afferent nerves–spinal cord, are represented figuratively.

In musculoskeletal disorders, the original injury occurs in the peripheral tissues and it is here that orthopedic pain therapy acts.

Stages in the Development of Pain

Noxious stimuli (1 on Fig. 1.1) are events or substances that are damaging to tissues, or are a threat to them. They activate the nociceptors in bone, muscles, tendons, and joint capsules. Mechanical, chemical, and thermal exogenous stimuli act first of all on the musculoskeletal system. The direct trigger for muscular reactions as part of the vicious circle of pain and in the presence of continual psychological stress (endogenous pain) is unknown. Nevertheless, the process leading to the perception of pain is the same.

Nociceptors (pain receptors) (2) are nerve fibers, usually unmyelinated, that are activated when pain stimuli act on the body. The excitation threshold of the nociceptors is exceeded only by tissue-damaging irritants. The receptiveness of the musculoskeletal system to pain stimuli is dependent on the concentration of nociceptors and their thresholds. A nociceptor’s response (the impulse frequency) typically corresponds to the amount of pain stimulus, increasing to the point at which tissue is damaged (Meßlinger 1997).

NOTE

Muscles, periosteum, tendons, and joint capsules contain polymodal nociceptors that react to mechanical, chemical, and thermal stimuli.

Histologically, musculoskeletal nociceptors consistmainly of noncorpuscular (free) nerve endings. They are found on the small blood and lymphatic vessels within the connective tissue spaces and on the nerves themselves, as a so-called endoneurium (Mense 1977).

NOTE

Pain sensations originating from the musculoskeletal system form the numerically largest group within the somatosensory system because the concentration of nociceptors in periosteum, ligaments, and joint capsules is high.

Afferent fibers (3): Pain signals are transmitted via afferent nerve fibers from the nociceptors to the spinal cord. Unlike dorsal column afferents, the afferent axons are thin and myelinated (Aδ-fibers) or unmyelinated (C-fibers). Visceral afferent fibers are also mostly unmyelinated.

Transmission of Nociceptive Signals

Spinal cord (4): Synapses connect the nociceptive afferents (Aδ- and C-fibers) to the neurons of the posterior horn. Impulses occurring at this switch point in the spinal cord result in the release of excitatory neurotransmitters such as L-glutamate and substance P. L-Glutamate is believed to be an important transmitter in the CNS (Zieglgänsberger and Tölle 1993). Along with other neuropeptides (e. g., substance P), L-glutamate transmits the excitatory signals from the thin nociceptive nerve fibers to the nerve cells, which in turn transmit information to the spinal cord. The nociceptive influx is transmitted from the spinal cord by the following routes, among others:

- via the spinothalamic tract to the more superiorly lying areas of the brain (limbic system and thalamus)

- to segmental neurons that are connected to the motor and autonomic reflex arcs.

The nociceptive spinal cord neurons, the so-called multireceptive neurons, receive a converging influx of signals from multiple afferents from one organ or from different organs, e. g., skin and muscle, skin and viscera. This arrangement is an important prerequisite for referred pain (Schmidt and Thews 1997). Interneurons in the posterior horn modulate the activity in these multireceptive neurons. Their activity may reduce the transmission of nociceptive signals (gate control theory; Melzak and Wall 1965).

Perception of Pain

Cortex (5): The pain impulse is transmitted to the cortex via the ascending pathways. The CNS is responsible for the integration of pain perception and the reaction to it. Parts of the pain process can be allocated to individual structures within the CNS (Zieglgängsberger and Tölle 1993).

Information about pain is integrated into the regulation of circulation and breathing within the brainstem. It is here that the descending inhibitory systems can be found. These systems play a part in the endogenous regulation of pain in the spinal cord. Inhibitory systems are constantly active in the CNS, regulating sensitivity and reaction readiness. The action of these descending and segmentally inhibitory systems can be strengthened by a variety of pain therapy methods (Zieglgänsberger and Tölle 1993). Endogenous pain inhibition is activated by electrical stimulation (TENS), morphine, afferent stimulation (acupuncture), psychological influences (stress), and movement (sport and exercise; Dietrich 2003).

NOTE

A special aspect of orthopedic pain therapy is the use of movement to reduce pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree