INTRODUCTION

The common methods of wound care are reasonably effective, resulting in a good outcome for the vast majority of cutaneous wounds treated in the ED.1,2,3 Wound preparation is the most important step in restoring tissue integrity and function, minimizing infection risk, and achieving the best possible cosmetic result. However, there is surprisingly little scientific validation for most of these methods.4,5,6,7 With some patient and wound characteristics (Table 40-1), the risk of improper healing increases, and the importance of careful wound preparation becomes more important.4,5,8,9,10

| Patient Factors | Wound Factors |

|---|---|

Immunosuppression: diabetes, chemotherapeutic agents, chronic steroid therapy, chronic renal failure, hematologic malignancies, congenital immunodeficiencies Tissue ischemia: peripheral vascular disease, anemia, vasculitis Poor wound healing: elderly, cigarette smoking, malnourished, connective tissue disorders | Crush injuries Tissue loss Contamination Foreign bodies Peripheral location |

ANESTHESIA

Thorough cleansing and meticulous wound evaluation and repair can be painful procedures, so adequate anesthesia is important for patient comfort and cooperation. Choice of anesthetic agent and route varies according to wound location and size (see chapter 36, Local and Regional Anesthesia). The sensory, motor, and vascular examination should be performed at and distal to the wound site prior to the administration of local or regional anesthetic.

Sensory examination should include evaluation of pain or touch. If a wound involves the hand or fingers, additional assessment for digital nerve injury using two-point discrimination (normal <6 mm) on the volar pads should be performed prior to local or regional anesthesia administration. Motor examination should assess movement and strength of tendons and muscles around the wound site as well as muscles that are innervated by nerves traversing the site. Vascular examination should assess distal perfusion by noting skin color, temperature, capillary refill time, and quality of pulses. Comparison of the systolic blood pressure in the injured extremity with the noninjured one (using a Doppler stethoscope and pneumatic cuff) assesses for hemodynamically significant arterial compromise. While performing the sensory examination prior to the administration of an anesthetic is important, adequate motor examination can be occasionally limited by pain, with improved strength testing following achievement of pain control.

IRRIGATION

Wound irrigation is widely considered to be the most important step in the management of acute wounds; it decreases bacterial count and helps to remove debris and foreign bodies, thereby reducing the risk of wound infection.1,3,11 Choices in the performance of wound irrigation include solution composition, temperature of the irrigant, pressure with which it is applied, and the total volume used.

In most medical settings, wound irrigation is performed with sterile normal saline, but potable tap water is as effective and may be superior when taking into account time, resources, cost, and the potential for occupational exposures during clinician-performed irrigation techniques.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Limited studies indicate that dilute solutions containing povidone-iodine or hydrogen peroxide do not appear to confer greater benefit than water alone.18,19,20 Polyhexanide (a chlorhexidine polymer) is an antiseptic that, when used for wound irrigation of dirty and contaminated soft tissue wounds, reduced the rate of postrepair wound infections compared to Ringer’s lactate, povidone-iodine, or hydrogen peroxide irrigation.21,22,23 One small clinical trial suggests that warmed solution may be more comfortable than room temperature irrigant.24

High-pressure irrigation is defined as approximately 7 psi (50 kPa) or greater, and is achieved using any combination of a 30- to 65-mL syringe and a 19-gauge catheter or needle hub, or commercially available splashguard, with forceful depression of the syringe piston.3,25,26,27,28 Low-pressure irrigation is defined as approximately 0.5 psi (3.5 kPa) or lower, and is achieved with a slow, gentle wash.29 Low-pressure irrigation may be sufficient for cleansing simple, nonbite, uncontaminated wounds in highly vascular areas such as the scalp and face.30 However, high-pressure irrigation is generally regarded as more effective for clearance of debris and reduction of infection.11,16,31

Wound soaking is not effective in cleansing contaminated wounds and may actually increase wound bacterial counts.32 Routine scrubbing of traumatic wounds with a sponge is also ineffective, inflicting trauma and impairing resistance to infection.

Many wounds and lacerations seen in the ED have little visible contamination, and there is no strong evidence regarding the amount of irrigation effective to minimize postrepair infection. Common sense dictates that the higher the volume of irrigation, the more thoroughly cleansed the wound and the less likely infection will ensue. Typical recommendations by wound care experts range from 25 to 100 mL/cm of wound length for “clean”-appearing wounds.11 Additional volumes should be based on anatomic location, mechanism of injury, degree of contamination, and patient factors that lower resistance to infection.

High-pressure wound irrigation risks mucous membrane exposure of the healthcare worker to contaminated body fluids. Irrigation shields provide some measure of safety,28 but universal precautions, including barrier protection with face mask/shield, should be employed as a matter of routine.

SKIN DISINFECTION

A common practice is to disinfect intact skin around the wound with either a povidone-iodine–based or chlorhexidine-containing agent. These agents suppress bacterial growth on intact skin and are thus favorable antiseptics prior to surgical incision,33,34,35 but within the environment of an already open wound, they can impair host defenses and promote bacterial growth. Both povidone-iodine36,37 and chlorhexidine38 can produce chemical burns on intact skin and in the eyes. Apply disinfectants from the wound edges outward in order to avoid cytotoxic exposure of nonintact skin.10,11,20

STERILE TECHNIQUE

Although observing sterile technique has been well demonstrated to have a beneficial effect on patient outcomes in several settings, the extent to which its routine employment in the ED treatment of traumatically contaminated wounds reduces infection rates is unclear. Adherence to full aseptic methods (cap, gown, mask, and gloves) does not appear to be of substantial benefit,39 nor does hand antisepsis prior to initiation of wound repair.40 Although recommendations exist for the use of sterile gloves in the repair of uncomplicated lacerations, supportive evidence is lacking, if not refutative.41 These findings suggest that aspects of the sterile technique may be curbed, leading to time and cost savings per laceration by using common-sense cleanliness.

HEMOSTASIS

To adequately evaluate a wound, hemostasis is needed to prepare a clear visual field. The most common sources of wound-related bleeding are the subdermal plexus and superficial veins. Oozing from these sources can usually be controlled with the application of direct pressure using saline-soaked sponges or gauze.

In the event of continual bleeding, the next step is typically an attempt at chemical hemostasis using epinephrine mixed with local anesthetics in concentrations of 1:100,000 or 1:200,000 and injected into the wound area. Local epinephrine induces vasoconstriction that will additionally allow a longer duration of anesthesia and a larger total local anesthetic dose due to the depot effect of the vasoconstriction.42,43,44,45 Despite the theoretical risk of end-organ ischemia (i.e., fingers, nose, ears, toes), when mixed with local anesthetics, the safety of epinephrine use in these regions has been well documented.46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 Use caution in patients with small vessel disease, where end-organ epinephrine injection remains ill advised. Although epinephrine interferes with wound healing in experimental animal models,4,5 no increase in wound infection has been observed with the addition of epinephrine to local anesthetics used in the ED.

Physical means of applying pressure to bleeding include the use of gelatin, cellulose, or collagen sponges placed directly into the wound. Denatured gelatin (Gelfoam®; Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY) has no intrinsic hemostatic properties and works by the pressure it exerts as it expands. A cellulose derivative (Oxycel®; Becton Dickinson Infusion Therapy Systems, Inc., Sandy, UT) or a collagen (Actifoam®; MedChem Products, Inc., Woburn, MA) sponge reacts with blood, forming an artificial clot. These products are not particularly effective for actively bleeding wounds, as the blood flowing into the wound can wash them out.

If the source of bleeding is a small vessel that has been lacerated but can be easily visualized, control may be achieved through direct pressure applied with a gloved fingertip directly on the vessel. Once bleeding has ceased, more permanent control can be obtained by clamping the vessel, isolating a short length, and ligating it with absorbable synthetic suture (typically 5-0). Take care to avoid clamping or ensnaring adjacent structures (i.e., nerves and tendons), particularly when working with wounds of the face.

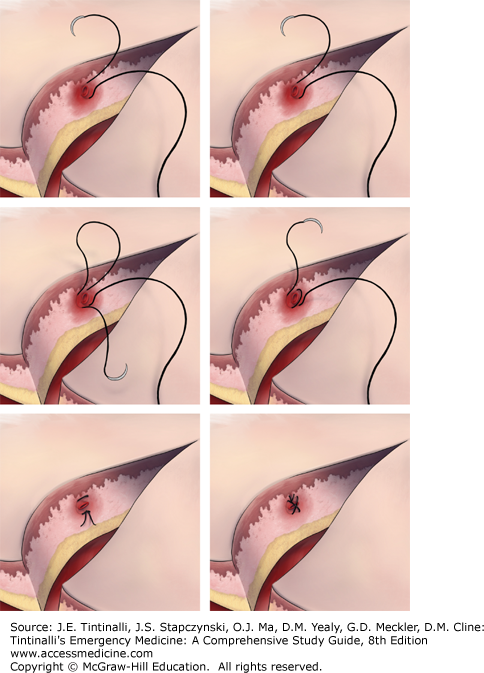

For bleeding wound edges where the involved vessel is not visible, a figure-of-eight or horizontal mattress suture (Figure 40-1) applied adjacent to the site of bleeding will sometimes achieve control. However, this technique may impair blood flow and leave nonviable tissue in the wound.

Bipolar electrocautery can achieve hemostasis in blood vessels <2 mm in diameter, but if improperly or too extensively applied, it can result in tissue necrosis. Electrocautery units are not routinely available in many EDs. Battery-powered, hand-held cautery devices (Figure 40-2), although more accessible, do not generate sufficient heat to produce coagulation in vessels larger than capillaries. Low-temperature units, identified where the wire loop does not glow when heated, are recommended for ED use.