PRINCIPLES OF INITIAL EVALUATION

Evaluation of the patient with a traumatic wound begins with overall patient assessment.1,2 Less obvious but more serious life-threatening injuries need care before directing attention to wound management. Determine the patient’s past medical history and circumstances surrounding the injury.1,2 Remove rings or other circumferential jewelry as soon as possible so they do not act as constricting bands when swelling progresses. Remove clothing over the injured area to reduce the potential for contamination.

External bleeding can usually be controlled by direct pressure over the bleeding site. When possible, replace skin flaps to their original position before applying pressure in order to avoid exacerbating vascular compromise. Tourniquet application may be necessary to stop life-threatening exsanguination or when needed for a short period to create a “bloodless” field for wound inspection.3,4,5 Amputated fingers or extremities should be wrapped with a moist, sterile, protective dressing, placed in a waterproof bag, and then placed in a container of ice water for preservation and consideration for future reattachment. Before wound exploration, cleansing, and repair, most patients will need some form of anesthesia.6 Systemic analgesia or procedural sedation may be required (see chapter 35, Acute Pain Management, and chapter 37, Procedural Sedation).

RISK ASSESSMENT

Proper wound management begins with a pertinent patient history (Table 39-1).1,2 A variety of patient factors have adverse effects on wound healing and increase the rate of wound infection—extremes of age, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, obesity, malnutrition, the use of immunosuppressive medications, the presence of connective tissue disorders, and protein and vitamin C deficiencies.1 Predictive factors for infection are the wound characteristics of location, age, depth, configuration, and contamination.7,8

Symptoms Pain, swelling, paresthesias, muscle weakness Type of force causing injury Crush (blunt) or shear (sharp) Bite or puncture Elements of contamination Time elapsed from injury until initial cleansing Time elapsed from injury until presentation Wound care performed prior to ED arrival Object that caused injury (glass, wood, etc.) Cleanliness of body and environment at time of injury and afterward Factors resulting in injury Intentional or unintentional Occupation or nonoccupation related Assault or self-inflicted Foreign body potential Did the object break or shatter? Foreign body sensation Removal of portion of object Function Occupation and handedness Allergies Anesthetics, analgesics, antibiotics, and latex Medications Chronic medical conditions that increase risk of infection Chronic medical conditions that increase likelihood of poor wound healing Previous scar formation (hypertrophic scars or keloids) |

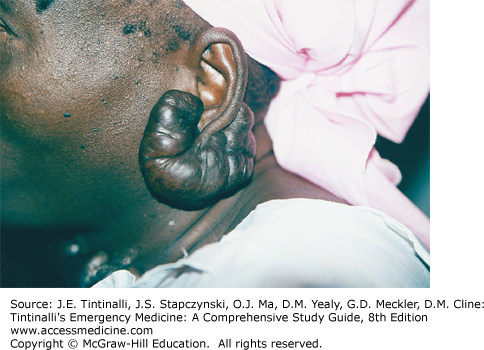

Ascertain the tendency of patients to form hypertrophic scars or keloids by both history and examination, as past experience may predict poor scar formation. Black and Asian patients are more prone to keloid formation than whites. Hypertrophic scars are due to tissue tension during wound healing, and these scars stay within the original wound boundaries and tend to undergo partial spontaneous regression within 1 to 2 years. Keloids are genetically linked variations in wound healing, resulting in the production of excess collagen beyond the original wound boundaries (Figure 39-1). Once they form, keloids rarely decrease in size.

FIGURE 39-1.

A large keloid extending beyond the original wound margins. [Reproduced with permission from Sztajnkrycer MD, Trott AD: Wounds and soft tissue injuries, in Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB (eds): Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 2nd ed. Figure 18-37. Copyright © 2002, 1997, by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.]

Obtain a detailed history of allergies or prior adverse reactions to anesthetic agents or antibiotics. Review any prior allergies to latex.9 Determine the status of prior tetanus immunization and the need for further tetanus vaccination (see chapter 156, Tetanus).

Review the mechanism of injury to identify the presence of potential wound contaminants and foreign bodies. Bite wounds are at high risk for infection and are generally managed differently than other lacerations (see chapter 46, Puncture Wounds and Bites). Foreign bodies are common in puncture wounds, wounds associated with broken glass, and motor vehicle collisions.10,11,12,13 Ask about the presence of a foreign body sensation. In adults, those reporting a foreign body sensation are more likely to have a retained foreign body than those who do not (positive likelihood ratio = 2.49 and negative likelihood ratio = 0.69).14 This question has little utility in children.15

Both foreign body retention and visible contamination increase the risk of infection.7,8 Organic and inorganic components of soil can cause infection even from very small doses of bacterial inoculum. Clay is the major inorganic soil component responsible for infection. Conversely, sand grains and black dirt from roadways are relatively inert.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree