INTRODUCTION

The major goal of wound closure is to restore the skin’s integrity in order to reduce the risk of infection, scarring, and impaired function. This may be achieved by one of three methods: primary, secondary, and delayed closure. With primary closure, the wound is immediately closed by approximating its edges, with the main advantage being a reduction in healing time in comparison with other closure methods. Primary wound closure also may reduce bleeding and discomfort often associated with open wounds. Secondary wound closure, in which the wound is left open and allowed to close on its own, is particularly well suited for highly contaminated or infected wounds as well as in patients at high risk of infection. Although this method may reduce the risk of infection, it is relatively slow and uncomfortable and leaves a larger scar than primary closure. With delayed (or tertiary) closure, the wound is initially cleansed and then packed with dry sterile gauze covered by a sterile covering. The dressing is left undisturbed unless signs of infection—fever, purulent exudate, or spreading cellulitis—develop. After 4 to 5 days, the dressing is removed, and the wound edges can be closed if no infection has supervened. This approach may be useful for highly contaminated wounds and animal bites, and while commonly described and recommended, there is little evidence documenting the effectiveness for traumatic wounds seen in the ED.1

OVERVIEW OF WOUND CLOSURE METHODS

Lacerations may be closed by one of five commonly available methods or devices: sutures, staples, adhesive tapes, tissue adhesives, and hair apposition. Each method has advantages and disadvantages (Table 41-1). Choice of the wound closure method and timing should take into account both patient and wound characteristics.2 Cosmetic outcome is more closely related to practitioner technique and the patient’s own healing characteristics than to any specific closure method or device. Many of the principles discussed in this chapter are based on experience and observation rather than on controlled trials.

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Sutures | Time honored Meticulous closure Greatest tensile strength Lowest dehiscence rate | Requires removal (if using nonabsorbable material) Requires anesthesia Risk of needle stick to physician Greatest tissue reactivity Highest cost Slowest application |

| Staples | Rapid application Low tissue reactivity Low cost Low risk of needle stick | Less meticulous closure May interfere with some imaging techniques (CT, MRI) Requires removal |

| Tissue adhesives | Rapid application Patient comfort Resistant to bacterial growth No need for removal Low cost No risk of needle stick Microbial barrier Occlusive dressing | Lower tensile strength than 5-0 or larger sutures Dehiscence over high-tension areas (joints) Not useful on hands Cannot bathe or swim (can shower) |

| Adhesive tapes | Least reactive Lowest infection rates Rapid application Patient comfort Low cost No risk of needle stick | Frequently fall off Lower tensile strength than sutures or tissue adhesives Highest rate of dehiscence Often requires use of toxic adjuncts Cannot be used in areas with hair Cannot get wet |

| Hair apposition | Simple Low cost No foreign body placed in wound No risk of needle stick | Can only be used on the scalp Can only approximate simple nongaping lacerations |

One of the most important considerations when choosing a wound closure method is the amount of tension on the wound, both static (at rest) and dynamic (with motion). Linear lacerations subject to little tension can usually be closed by any one of the five closure methods. For low-tension lacerations, consider patient characteristics and preferences such as compliance, the availability to return for follow-up and device removal, and overall level of patient anxiety. With low-tension irregular lacerations, sutures may be the best alternative, allowing the greatest degree of precision for accurate wound edge approximation. Conversely, some small lacerations that would typically be closed may not actually benefit from primary closure. For example, simple (<2 cm) uncomplicated hand and finger lacerations, when treated with antibiotic ointment and gauze dressing, heal as fast and with no notable differences in appearance or function as those closed primarily with sutures.3 But note that this technique is limited to small, superficial hand lacerations; it cannot be recommended for larger lacerations and in other sites.

With lacerations subject to high tension (static and/or dynamic) one can relieve the amount of tension on the wound in order to avoid early dehiscence or gradual widening of the scar. Relief of tension is best achieved by careful undermining, placement of deep dermal sutures, and wound immobilization (when appropriate). After placement of deep, tension-relieving sutures, the superficial epidermal layer may be closed by any of the aforementioned closure methods. Reinforcement with adhesive skin tape is useful when the skin is thin, as in pretibial lacerations.4,5,6

With patients at risk of keloid formation, it makes logical sense to relieve tension and minimize the amount of foreign material introduced into the wound. Skin tapes or tissue adhesives, instead of sutures, can minimize the amount of foreign material and inflammation that may increase the likelihood of excessive scar formation.

SUTURES

Sutures are the strongest of all the closure devices and allow the most accurate approximation of the wound edges, regardless of their shape or configuration. However, sutures are the most time-consuming and operator dependent of all wound closure methods and have the risk of inadvertent needle-stick injury. Using forceps to handle the needle during suturing can reduce this risk. A needle-catcher device is reported to be useful in reducing needle-stick injury during skin suturing.7,8,9

Sutures may be classified as absorbable and nonabsorbable. Nonabsorbable sutures retain their tensile strength for at least 60 days. They are most often used to close the outermost layer of the skin (where they can be removed) or for repair of tendons (where prolonged strength is necessary due to very high tension). In general, nonabsorbable sutures are avoided in deep vascularized tissues where their presence stimulates a foreign body response with fibroblastic proliferation. Nonabsorbable sutures are differentiated by their origin and structure (Table 41-2). Due to their strength, handling, and relatively low tissue reactivity, synthetic monofilament sutures (such as nylon or polypropylene) are preferred. Polybutester sutures have the ability to elongate in response to external forces and possess elasticity to return to the original size once the load is removed. This property may be useful in wounds where swelling is anticipated. Less distensible sutures, such as nylon or polypropylene, cannot expand, and instead may lacerate the wound edges as the tissue swells.

| Suture | Structure | Raw Material | Tensile Strength Retention Profile | Tissue Reactivity | Common ED Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silk | Braided | Organic protein fibroin | Degradation of fiber results in loss of strength over many months | Significant inflammatory reaction | Intraoral mucosal surfaces for comfort |

| Nylon (Ethilon®, Dermalon®) | Braided and monofilament | Polyamide polymer | Hydrolysis results in 20% loss in strength per year | Minimal | Soft tissue and skin reapproximation |

| Polypropylene (Prolene®, Surgipro®) | Monofilament | Polypropylene polymer | Indefinite | Least | Soft tissue and skin reapproximation |

| Polyester (Mersilene®, Ti·Cron®) | Braided and monofilament | Polyethylene terephthalate polymer | Indefinite | Minimal | Tendon repair using undyed (white) color |

| Polybutester (Novafil®) | Monofilament | Copolymer of butylene terephthalate and polytetramethylene ether glycol | Indefinite | Minimal | Soft tissue approximation |

Absorbable sutures lose most of their tensile strength in less than 60 days. As a result, they are well suited for closure of deep structures such as the dermis and fascia (Table 41-3). Poliglecaprone 25 has handling characteristics that are similar to nonabsorbable sutures (such as nylon) and is particularly useful for intracuticular or subcuticular closure. Due to its rapid absorption, poliglecaprone 25 should probably be limited to relatively low-tension wounds. With high-tension wounds, a suture with more sustained tensile strength is preferred. Absorbable sutures that incorporate the antibacterial agent triclosan are also available and may be especially indicated in contaminated wounds.10,11 Rapidly absorbing sutures can also be used to close the superficial skin layers, especially when avoidance of suture removal is desirable.12,13,14,15

| Suture | Structure | Raw Material | Tensile Strength Retention Profile | Absorption Rate | Tissue Reactivity | Common ED Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical gut | Monofilament | Collagen derived from beef serosa or sheep submucosa | 7–10 d | Absorbed by proteolytic processes in 70 d | Moderate reactivity | Intraoral wounds |

| Chromic gut | Monofilament with chromic salt coating | Collagen derived from beef serosa or sheep submucosa | 21–28 d | Absorbed by proteolytic processes in 90 d | Moderate reactivity | Subcutaneous approximation and intraoral wounds |

| Fast-absorbing gut | Monofilament heat treated to facilitate absorption | Collagen derived from beef serosa or sheep submucosa | 5–7 d | Absorbed by proteolytic processes in 21–42 d | Moderate reactivity | Facial wounds and skin grafts |

| Polyglycolic acid (Dexon®) | Braided | Glycolic acid polymer | 65% at 14 d and 35% at 21 d | Absorbed by hydrolysis, complete by 60–90 d | Minimal | Subcutaneous approximation and ligation of vessels |

| Coated polyglactin 910 (Vicryl®) | Braided | Copolymer of lactide and glycolide, coated with polyglactin 370 and calcium stearate | 75% at 14 d and 40% at 21 d | Absorbed by hydrolysis, complete by 56–70 d | Minimal | Subcutaneous approximation and ligation of vessels |

| Coated polyglactin 910 with triclosan (Vicryl PLUS®) | Braided | Copolymer of lactide and glycolide, coated with polyglactin 370 and calcium stearate; incorporates antibacterial agent triclosan | 75% at 14 d, 50% at 21 d, and 25% at 28 d | Absorbed by hydrolysis, complete by 56–70 d | Minimal | Subcutaneous approximation and ligation of vessels, especially useful in contaminated wounds |

| Coated polyglactin 910 rapid absorption (Vicryl Rapide®) | Braided | Copolymer of glycolide and lactide, coated with polyglactin 370 and calcium stearate | 50% by 5 d and 0% at 14 d | Absorbed by hydrolysis, complete by 42 d | Minimal to moderate | Skin approximation when absorbable sutures are used |

| Coated glycolide and lactide (Polysorb®) | Braided | Copolymer of glycolide and lactide, coated with mixture of caprolactone, glycolide copolymer, and calcium stearoyl lactylate | 80% at 14 d and 30% at 21 d | Absorbed by hydrolysis, complete by 56–70 d | Minimal | Subcutaneous soft tissue approximation |

| Polydioxanone (PDS II®) | Monofilament | Polyester polymer | 70% at 14 d, 50% at 28 d, and 25% at 42 d | Absorbed by hydrolysis, complete at 180–210 d | Slight | Subcutaneous soft tissue approximation where more prolonged strength is needed |

| Poliglecaprone 25 (Monocryl®) | Monofilament | Copolymer of glycolide and epsilon-caprolactone | 50–70% at 7 d and 20–40% at 14 d | Absorbed by hydrolysis, complete by 91–119 d | Minimal | Subcutaneous soft tissue approximation |

| Poliglecaprone 25 with triclosan (Monocryl PLUS®) | Monofilament | Copolymer of glycolide and epsilon-caprolactone; incorporates antibacterial agent triclosan | 50–70% at 7 d and 20–40% at 14 d | Absorbed by hydrolysis, complete by 91–119 d | Minimal | Subcutaneous soft tissue approximation; especially in contaminated wounds |

| Glycomer 631 (Biosyn®) | Monofilament | Polyester composed of glycolide, dioxanone, and trimethylene carbonate | 75% at 14 d and 40% at 21 d | Absorbed by hydrolysis, complete by 90–110 d | Slight | Subcutaneous soft tissue approximation where extended strength is not needed |

| Polyglyconate (Maxon®) | Monofilament | Copolymer of glycolic acid and trimethylene carbonate | 80% at 7 d, 75% at 14 d, 65% at 21 d, 50% at 28 d, and 25% at 42 d | Absorbed by hydrolysis, complete by 180 d | Slight | Subcutaneous soft tissue approximation where more prolonged strength is needed |

For most ED use, the choice between absorbable and nonabsorbable material for percutaneous sutures is clinically irrelevant.12,13,14,15 The cosmetic outcomes and complications of traumatic lacerations and surgical incisions closed with absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures have similar short- (infection, dehiscence) and long-term (cosmesis) outcomes.16 Absorbable sutures, like rapidly absorbing gut, are especially useful for skin closure in children who are not candidates for wound repair with skin tapes or tissue adhesives.

Suture material is categorized by the U.S. Pharmacopeia gauge size. The larger the suture size number, the thinner the suture, so that, for example, a 6-0 suture is thinner than a 5-0 suture. A general principle is that larger-diameter material produces more damage to the tissues and leaves larger holes in the skin, so generally thinner suture material is used whenever possible. Because smaller-diameter material has less strength, the trade-off is that more individual sutures closer together are sometimes needed to close a wound. Where cosmetic appearance is important, as on the face, smaller-diameter material is preferred (Table 41-4).

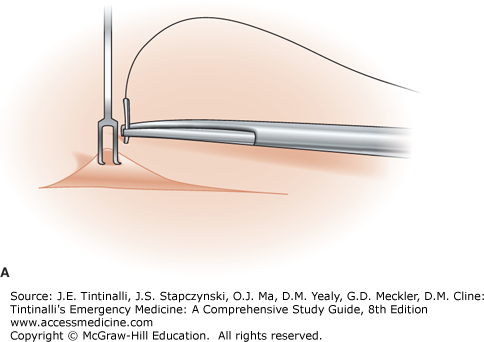

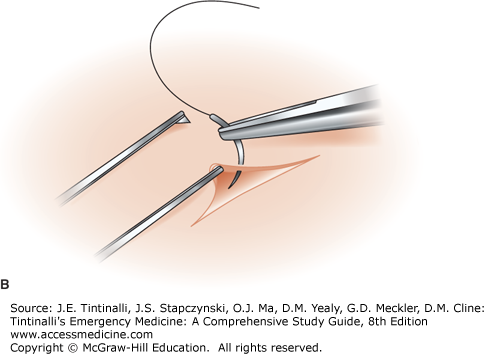

Improper tissue handling further traumatizes the tissues and results in an increased risk of infection and poor scarring.17 Gentle tissue handling using either skin hooks or the open limb of fine forceps is encouraged (Figure 41-1). Magnifying lenses such as surgical loupes can assist in accurate placement of sutures. While there are many types of surgical loupes available, a version useful in the ED is a magnifying power of 2.5× with the Keplerian lens system, which will provide a bright, clear image out to a field of view of 10 cm. Hemostasis is best achieved by direct pressure. Topical vasoconstrictors (such as epinephrine) applied to the wound edges and bed or mixed with the local anesthetic injected into the wound may help control bleeding in traumatic lacerations treated in the ED. With bleeding from vessels >2 mm in diameter, careful and selective placement of a ligature tie is often necessary. Electrocautery increases the risk of wound infection and scarring.17 The technique requires training and policies for its use, to ensure patient and healthcare professional safety.

The best cosmetic outcome is achieved by carefully matching each layer of the wound with its corresponding counterpart on the opposite side, ensuring eversion of the wound edges and minimizing the amount of tension on the wound. As the wound heals and the swelling subsides, the wound will eventually flatten, becoming flush with the surrounding skin surface. Inadvertent inversion of the wound edges may result in an unsightly depressed scar. A variety of suture techniques can be used to handle wounds of nearly all shapes, irregularities, and depths (Table 41-5).

| Suture Type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Frequent Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interrupted percutaneous | Excellent approximation for irregular and complex lacerations | Time-consuming May strangulate tissues | Low-tension wounds May be used with deep sutures for high-tension wounds |

| Continuous percutaneous | Rapid closure Accommodates edema | Less meticulous closure than interrupted sutures Wound may dehisce if a single knot unravels and no deep sutures were placed | Percutaneous closure in conjunction with deep sutures |

| Deep dermal | Reduces tension on wound surface Allows early removal of percutaneous sutures, avoiding hatch marking May reduce scar width | May increase infection in contaminated wounds | High-tension wounds Closure of dead space |

| Continuous subcuticular | Rapid Reduces tension on wound surface Reduces or eliminates need for percutaneous sutures May reduce scar width | Technically difficult Less accurate approximation than interrupted sutures Wound may dehisce if a single knot unravels | Cosmetically visible areas to reduce scarring |

| Vertical mattress | Excellent wound edge eversion Combines advantages of deep and superficial sutures | May cause tissue strangulation | Thin or lax skin with little dermal or fascial tissue High-tension areas (e.g., extremities) |

| Horizontal mattress | More rapid than simple interrupted sutures Avoids punctures close to wound edges that may impair perfusion Accommodates wound swelling | Requires skill to achieve wound edge eversion | Volar wounds of the hands Initial approximation of high-tension wounds |

| Half-buried horizontal mattress | Less compromising to flap tip perfusion and stellate lacerations | Technically difficult | Corner stitches and flaps Stellate lacerations |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree