Chapter 16

Workplace rehabilitation

High cost of pain and work disability

Allied health professional role

Knowledge and skills required for workplace rehabilitation

Evidence-based principles for return to work for all stakeholders

The workplace rehabilitation process

A new paradigm: an emphasis on communication

Return-to-work programme hierarchy

Workplace assessment and modified work/suitable duties programmes

Suitable duties programmes: the cornerstone of return-to-work programmes

Improving the work environment

At the end of this chapter readers will have an understanding of:

1 The role of the workplace rehabilitation consultant in helping the injured worker to return to work.

2 Ways in which the injured worker, co-workers, employers and other relevant parties can all contribute to the overall success of a return-to-work programme.

3 The steps involved in a return-to-work programme for the injured worker.

4 Different models and assessments that can be applied to assist a worker in need of rehabilitation.

5 Ways in which workloads and/or workplaces can be adapted to suit the needs of the returning worker.

HIGH COST OF PAIN AND WORK DISABILITY

The high incidence of musculoskeletal disorders around the world tells us that many workers are either off work or working with pain. When a worker incurs an injury, work-related or not, that causes pain, there can be high costs, both to him or her personally and to the wider society. It is well established that pain has a high price in terms of its economic impact on a workforce and society (Access Economics 2007, Dagenais et al 2008) and that a small proportion of cases can contribute to a high proportion of the costs (Chou et al 2007, Maetzel & Li 2002). Therefore, there is increasing consensus that countries around the world need to implement strategies to reduce the costs of post-injury return to work (RTW), primarily by early intervention (Waddell & Burton 2005).

ALLIED HEALTH PROFESSIONAL ROLE

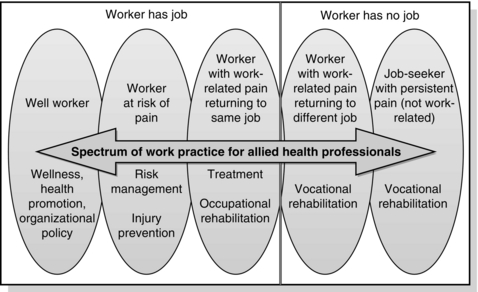

Around the world, the role of the health professional can be greatly influenced by the systems in place for intervention for workers with pain. They may only have a role in medical treatment and intervention, and little involvement with the workplace. They may be involved only if the worker claims workers’ compensation, and collaborate with the claimant and the insurer to develop a suitable or modified duties programme to get the worker back to functional employment. The allied health professional (AHP) may work with people with persistent pain who cannot return to their usual occupation and are considering returning to the workforce in a new occupation. At the other end of the spectrum, they may be heavily involved at the place of employment, liaising with workers and managers to provide workplace-based early intervention and injury prevention interventions (see Fig. 16.1).

The roles can be condensed into two broad categories of prevention and rehabilitation. Rehabilitation can be further categorized into the areas of occupational rehabilitation and vocational rehabilitation. These two types of workplace rehabilitation can have varying definitions around the world. Workplace rehabilitation is ‘a managed process involving timely intervention with appropriate and adequate services based on assessed need, and which is aimed at maintaining injured or ill employees in, or returning them to, suitable employment’ (Heads of Workers’ Compensation Authorities 2009, p. 5).

However, no matter what the definitions, the role of the AHP tends to depend on whether the person has a job to which he or she is aiming to return (usually called occupational rehabilitation) or the person is returning to the workforce in a different job or occupation (often called vocational rehabilitation). In the latter instance, the person may be unable to return to their prior occupation due to a work-related disability and, therefore, may still be covered by workers’ compensation or other insurance schemes, or the person may have developed a pain-related disability from non-work causes and is receiving welfare payments and rehabilitation to get back into the workforce after a period of disability. In many parts of the world, the spectrum of practice outlined earlier is referred to as disability management (Williams & Westmorland 2002). This spectrum is being extended further in some countries to encompass absenteeism management, where early intervention is provided no matter what the reason for days off work and whether the cause is work-related or not. It is even being extended to management of presenteeism, for workers who do not take time off work but are not at full productivity due to injury, illness or disability (Calkins et al 2000).

The role of the WRC is to coordinate services to ‘… achieve a cost effective, safe, early and durable return to work’ for the injured worker or job-seeker (Heads of Workers’ Compensation Authorities 2009, p. 6). This chapter will cover broad principles and services used in workplace rehabilitation to get the worker or job-seeker back to work and follow the common pathways for these clients in the workplace rehabilitation process. Two cases will be used to illustrate the typical presentation of the injured worker and job-seeker with persistent pain. An overview of some of the common strategies used in the WRC’s toolbox will be presented and current evidence-based principles presented for the reader to consider for practice.

KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS REQUIRED FOR WORKPLACE REHABILITATION

The AHP needs a range of knowledge and skills for their role in workplace rehabilitation. When working as a WRC, knowledge of the prevailing legislation, such as workers’ compensation, occupational health and safety, disability discrimination and welfare legislation, is essential, at least in terms of the implications of this legislation and related policies for the worker or job-seeker with whom they are working. There is also a need for a strong grounding in the nature, prognosis and functional impact of the pain-related injury, including the implications of current treatments for RTW issues, e.g. the effect of pain medications on driving (see Box 16.1). WRCs also need an understanding of measurement principles and programme evaluation to be able to demonstrate the evidence for their practice (Gibson et al 2002).

Prior to this, however, it is important to address a key issue that can be a major barrier for people returning to work. The role described above assumes health professionals accept that workers who have pain usually can indeed work. Some experts in the field have raised concerns that treating health professionals can at times compound the issues for workers returning to work, for example by certifying workers as unfit for all duties or by providing inaccurate education about resuming activity (Waddell & Burton 2006). Health professionals can also achieve this by concentrating, contrary to prevailing international evidence-based practice guidelines, on symptom management in the early and not-so-early stages after onset of work-related pain (Hush 2008), rather than explaining the benefits of staying at work (McGuirk & Bogduk 2007) and being actively engaged with the worker’s workplace to facilitate a safe and efficient RTW. In defence of health professionals, this can occur merely because they themselves need better education about work and workplaces (Royal Australasian College of Physicians 2009) or need systems that reimburse their time for such engagement with the workplace. However, no matter what role the health professional may have in their contact with the worker who has pain, he or she needs to be cognisant of the messages they give to the worker and how influential such messages can be for safe, early and effective RTW.

THE WORKER’S PERSPECTIVE

What about the worker with pain? The societal value of work cannot be underestimated. This is recognized by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (World Health Organization 2001), which includes participation in work as a major valued role. Workers with disabilities can face many barriers in returning to work, and some of the most influential can be attitudinal.

Qualitative research on the perspectives of workers with injuries in the workers’ compensation system and job-seekers with persistent pain gives insight to some of the major barriers people can face (Friesen et al 2001; Lippel 2007; Patel et al 2007). For example, a qualitative study of the effect of the workers’ compensation process on workers in Quebec found the stigma attached to being an injured worker a major barrier, with participants reporting that they need to deal with prejudice against injured workers and stereotypes about them playing the system (Lippel 2007). They also described the difficulty they experience in dealing with the imbalance of power in the workers’ compensation system, feeling ‘like David against Goliath’ (Lippel 2007, p. 435). These participants reported a high incidence of mental health issues during the workers’ compensation process, sadly with often greater disabling consequences than the initial injury itself. Despite these negative health effects, participants also identified the positive health effects of being in the process, such as more expedient access to health care and a valuable, supportive relationship with someone in power, such as a health professional or caseworker, who knew the system and the process.

Similarly, job-seekers with persistent pain reported appreciating the benefits they received through the welfare support system (Patel et al 2007). However, they reported feeling frustrated at the limited understanding of caseworkers and employers about persistent pain and its consequences for work ability, and at healthcare providers not taking their problem seriously (Patel et al 2007).

EVIDENCE-BASED PRINCIPLES FOR RETURN TO WORK FOR ALL STAKEHOLDERS

Before exploring the roles of AHPs in assisting workers or job-seekers with pain to RTW, this chapter will first explore seven principles that are needed for workplaces to achieve successful RTW after work disability (Institute for Work & Health 2007) (Box 16.2). These principles are particularly important for workplaces and employers, but can also inform the role of the AHP in supporting such RTW. These principles confirm the value of early and safe modified work, also called work accommodation or suitable duties programmes (SDPs), as the cornerstone of successful RTW (principle 2). The principles probably have the most implications for employers and workplaces in terms of their advocacy of a strong health and safety culture (1), with support of supervisors for work disability prevention and RTW planning in their duties (4), including early communication with injured or ill workers (5).

The challenges are many when working with employers to implement organizational change (Amick et al 2000; Whysall et al 2006). Consultants to employers may need to apply attitude and behaviour change theories, such as a transtheoretical approach to change, for individuals and organizations, and provide practical tools and techniques to enable managers to measure and tackle behavioural change. Employers also need to provide more budgetary control and time to managers to deal with health and safety issues, and flatten the hierarchy of decision-making systems about health and safety (Whysall et al 2006).

THE WORKPLACE REHABILITATION PROCESS

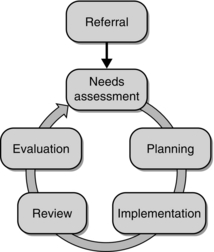

The basic common steps of the workplace rehabilitation process are outlined in Figure 16.2. The names and numbers of steps can vary around the world and with different systems; these are based on a national framework currently in place in Australia and cover the basic steps in most processes of getting workers or job-seekers back to work.

Fig. 16.2 Workplace rehabilitation process continuum. Adapted from Heads of Workers’ Compensation Authorities (2009).

The following section explains each of the steps in the process. It goes into more depth in some sections, such as planning (3), where an introduction to some models to assist planning and an overview of common services are provided. The steps are also illustrated by a companion case study (see Box 16.4) that provides further details of the individual processes followed within the overall process, such as conducting an initial needs assessment and developing a rehabilitation plan and SDP.