Thomas H. Taylor

West Nile Virus

West Nile virus (WNV) is now the leading cause of epidemic encephalitis in the United States. During the past 10 years, the face of meningoencephalitis has changed from predominantly enterovirus and herpes simplex virus to a broad and more geographically varied spectrum of disease. The morbidity associated with more neuroinvasive forms of WNV is considerable, and ongoing neurologic deterioration may be related to viral persistence.

Definitions

WNV is an arboviral infection of the family Flaviviridae (from Latin flavus, “yellow”), which includes the prototype, yellow fever, as well as dengue fever, Japanese encephalitis (JE), St. Louis encephalitis (SLE), and tick-borne encephalitis (TBE). These viruses have a predisposition to cause acute febrile illness and central nervous system infections, encephalitis, and aseptic meningitis. West Nile fever (WNF) and West Nile encephalitis (WNE) are outcomes of WNV. All Flaviviridae may invade muscle, joints, and liver and thus give rise to complications of myositis, arthritis, and hepatitis. Encephalitis, meningitis, myelitis, and neuritis refer to inflammation of brain, leptomeninges, spinal cord, and nerve roots, respectively. Radiculitis refers to involvement primarily of the sensory nerve root, and acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) refers to a myelitis involving the anterior horn cells, or motor cells, of the spinal cord; both conditions may complicate WNV infection. Meningoencephalitis, or inflammation of both meninges and brain, is common in WNV infection.

Transmission of arboviral infection (ar for arthropod and bo for borne, or arthropod-borne viral infection) is predominantly by mosquitoes but sometimes by ticks. Birds are the WNV reservoir (and amplifying host). Horses and humans are susceptible but dead-end hosts. Many other vertebrates are susceptible to infection, but like humans, most do not sustain high-level viremias for long enough periods to become a reservoir or amplifying host.

Epidemiology

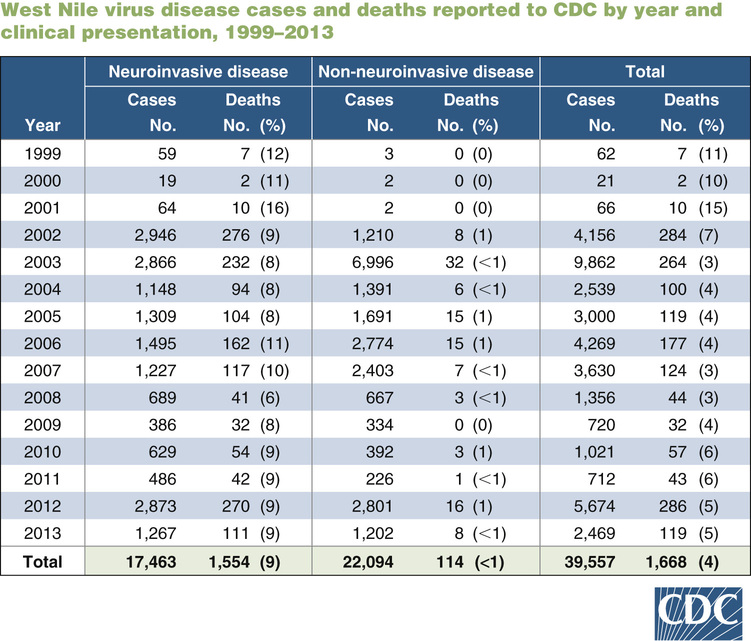

The evolution of WNV represents a true emerging infectious disease, with rapid spread throughout North America and now progressing to Central and South America, suggestive of what we might expect from the next influenza pandemic or acts of bioterrorism. WNV was first isolated from a febrile female patient in the West Nile district of Uganda in 1937 but was not associated with neurologic disease at that time. WNV did have close serologic identity with JE virus and SLE virus, two closely related and highly neurotropic viruses. For three decades, WNF, associated with fever, arthritis, and rash, circulated in Africa and the Middle East, with little neuroinvasive disease. The 1990s brought increasingly frequent and severe outbreaks of West Nile neuroinvasive disease (WNND) to Europe, Russia, and the Middle East, along avian migration routes. In 1999, WNV crossed the Atlantic and produced an outbreak of WNND in boroughs of New York City, epidemiologically associated with mosquito exposure.1 The New World strain was closely related to a newly emergent clade 1a strain circulating in the Middle East and may have arrived via a febrile traveler, a transported mosquito, or a storm-blown avian host. Like its Middle East counterpart, this virus was neuroinvasive and rapidly spread from New York by bird migration routes along the entire East Coast and subsequently westward to involve all lower 48 states (not Alaska or Hawaii).2 After emergence in the United States, WNV became the most common cause of neuroinvasive arbovirus disease, culminating in 9862 cases in 2003. A resurgence occurred in 2012 with 5674 cases, suggesting that WNV will follow a pattern of periodic outbreaks, as opposed to the more endemic pattern of other arboviruses circulating in the North America (Fig. 236-1).3

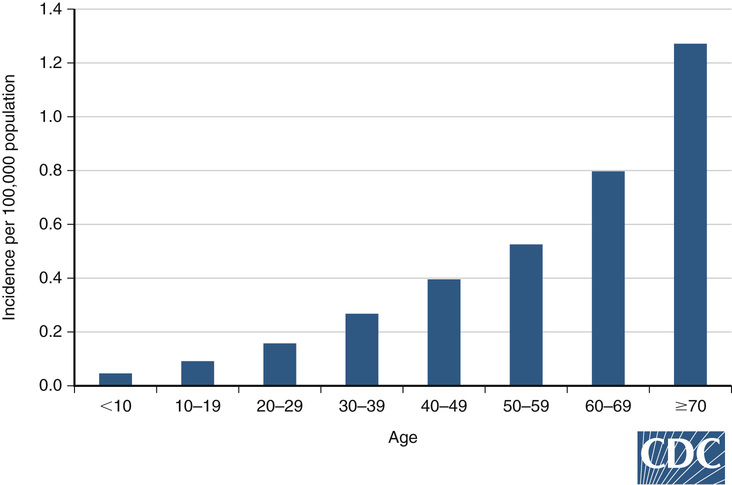

The virus is maintained in a bird-mosquito-bird cycle because wild birds develop high levels of viremia during long but relatively asymptomatic intervals, which facilitates transmission to many mosquitoes (amplification). Avian and mosquito active surveillance is now recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to facilitate early warning of impending community outbreaks. Culex mosquitoes transmit the WNV to humans and horses, which are incidental hosts with low-level viremia of short duration (i.e., dead-end hosts). There has been no incidental human-to-human or other vertebrate-to-human transmission. However, transmission by transfusion, transplantation, laboratory inoculation, breast milk, hemodialysis, and in utero infection has occurred.4 Most cases in North America have occurred in the late summer and early fall, in conjunction with high rates of mosquito WNV carriage. Children have high rates of infection but low rates of neuroinvasive disease, which is more likely to be aseptic meningitis as opposed to meningoencephalitis in adults.5 Adults older than 65 years have higher mortality and 110 times the incidence of WNND compared with children6 (Fig. 236-2).

Clinical Presentation

As with SLE and JE viruses, most infection with WNV is asymptomatic. Serologic surveys indicate that only 20% of infected persons develop WNF, and less than 1% develop WNND.7 Cases of neuroinvasive and non-neuroinvasive WNV reported to the CDC vary by year and state, but the total number of WNV infections can be estimated to be 50,000 annually (see Fig. 236-1).3

After an incubation period of 2 to 14 days, WNF is characterized by an influenza-like illness, fever, arthralgia, myalgia, rash, malaise, and headache. Gastrointestinal symptoms have included nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Generalized lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly are common.8 Rash appears early in 50% to 60% of cases and is a nonspecific maculopapular rash that most often begins on the trunk. Although WNV was confirmed serologically, the acute-phase serum tested negative at the time of rash in 57% of patients.9 Convalescent serum is often needed to confirm the diagnosis in this early and nonspecific stage of illness.

Weakness is a prominent feature of WNF, and myelitis, caused by infection of motor anterior horn cells, may lead to AFP reminiscent of poliomyelitis.10 As with poliovirus and more closely related JE and SLE viruses, a biphasic illness eventuates in aseptic meningitis (30%) and encephalitis (60%) as the second phase of illness after WNF.6 Prominent findings in patients with encephalitis are movement disorders: tremor, parkinsonism, gait disturbances, myoclonus, and rarely seizure disorder. These motor disturbances appear early, have a pathophysiologic correlation with lesions seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the basal ganglia and thalamus, and may resolve in ensuing months.6 AFP can be recognized as progressive weakness, often asymmetric and suggestive of stroke, and loss of deep tendon reflexes. WNV infection is associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), an autoimmune acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopathy distinguished by preceding sensory paresthesias, symmetric ascending weakness, loss of deep tendon reflexes, and autonomic dysfunction (see Chapter 195). Sensory and autonomic nerve involvements are not seen with AFP. It is important to distinguish between AFP and GBS because AFP is associated with little long-term improvement but GBS is largely reversible over time.7

Aseptic (nonbacterial) meningitis and encephalitis commonly follow the symptoms of WNF by 4 to 7 days but may appear without a recognized prodrome as stiff neck (meningismus), headache, and sensitivity to light (photophobia). These symptoms may further proceed to encephalitis characterized by alterations in consciousness: lethargy, confusion, stupor, and coma. More focal encephalopathic signs include difficulty with word finding, speech, and memory, sometimes advancing to seizures, cranial neuropathy, upper motor neuron paralysis with hyperreflexia, and extensor plantar responses. The hypothalamic-pituitary axis may become involved and is associated with central nervous system–mediated fever, hyponatremia resulting from the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), or diabetes insipidus (urinary water loss) caused by insufficient antidiuretic hormone.

Isolated acute febrile retinitis has recently been attributed to WNF. Fifty-two patients at a uveitis clinic had ocular symptoms after fever. Thirty-seven or 71% had at least two laboratory tests positive for WNV, and evaluation negative for other causes of retinitis. Visual acuity loss at final visit was common.11

Physical Examination

The general examination should include awareness of rash, arthritis, adenopathy, and splenomegaly. Photophobia is recognized by excessive reaction to bright light. Nuchal rigidity is recognized by passive flexing of the neck, which induces involuntary hip flexion (Brudzinski sign). More diffuse meningeal irritation is elicited by the Kernig sign: with hip flexed, attempts to extend the knee produce resistance and pain in the hamstring and back. Meningeal irritation in children may be recognized by tripoding, or sitting on the examination table supported by buttocks and both hands placed posterior, so as to maintain a rigid spine. Encephalitis is recognized by testing multiple areas of cognitive function, degree of alertness, speech, motor and sensory function, and cranial nerves. AFP may be recognized by abrupt onset of weakness and decreased deep tendon reflexes and may be distinguished from GBS by lack of autonomic or sensory nerve involvement.7 Disease may progress rapidly, and frequently repeated examinations are required to assess the need for increasing levels of supportive care (Table 236-1).

TABLE 236-1

Type of Weakness Associated with WNV Infection Compared with Other Motor Neuron Diseases

| Characteristic | AFP | GBS | WNV Weakness |

| Onset | With acute infection | 1-8 weeks after infection | With acute infection |

| Fever | Present | Absent | Present |

| Leukocytosis | Present | Absent | Present |

| Distribution | Often asymmetric | Symmetric ascending | Generalized |

| Sensory | No sensory loss | Paresthesias, sensory loss | No sensory loss |

| Autonomic symptoms | No autonomic symptoms | Autonomic symptoms | No autonomic symptoms |

| Deep tendon reflex | Absent | Absent | Present |

| Central nervous system involvement | Encephalopathy common | Absent | Meningitis, encephalitis |

| Cerebrospinal fluid profile | Pleocytosis, protein elevated | No pleocytosis, protein elevated | Pleocytosis and protein if meningitis, encephalitis |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree