INTRODUCTION

Vaginal discharge is caused by a wide variety of disorders, including vaginitis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.1 Vaginitis is a spectrum of diseases that cause vulvovaginal symptoms including burning, irritation, itching, odor, and abnormal discharge. The factors associated with acute vaginitis are listed in Table 102-1. The most common infectious causes of vaginitis in symptomatic premenopausal women are bacterial vaginosis (40% to 45%), vulvovaginal candidiasis (20% to 25%), and trichomoniasis (15% to 20%). Vulvovaginal candidiasis, contact vaginitis, and atrophic vaginitis may occur in virgins and postmenopausal women; however, the other forms of infectious vulvovaginitis are generally found in sexually active women. In approximately 30% of women with vaginal complaints, the disorder remains undiagnosed even after comprehensive testing.2,3,4

The clinical diagnosis may be challenging, because women may have more than one disease, and signs and symptoms are frequently not specific to a particular cause. Polymicrobial infection is not uncommon.

Although infectious vaginitis rarely requires hospitalization, it may have serious sequelae. Both bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis have been shown to be associated with premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, and low infant birth weight.5,6 Trichomoniasis is associated with pelvic inflammatory disease in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus and increases risk of human immunodeficiency virus acquisition and transmission.7,8 When overgrowth of certain bacteria occurs, the protective effect of vaginal lactobacilli strains, which inhibit the growth of bacteria and destroy human immunodeficiency virus in vitro, is lost.1

PHYSIOLOGY

In females of childbearing age, estrogen causes the development of a thick vaginal epithelium with a large number of superficial glycogen-containing cells and serves a protective function. Glycogen is used by the normal flora, such as lactobacilli and acidogenic corynebacteria, to form lactic and acetic acids. The resulting acidic environment favors the normal flora and discourages the growth of pathogenic bacteria. Lack of estrogen or a dominance of progesterone results in an atrophic condition, with loss of the protective superficial cells and their contained glycogen, and subsequent loss of the acidic environment.

Normal vaginal secretions vary in consistency from thin and watery to thick, white, and opaque. The quantity may also vary from a scant to a rather copious amount. Secretions are odorless and produce no symptoms. The normal vaginal pH varies between 3.8 and 4.5. Alkaline secretions from the cervix before and during menstruation, as well as alkaline semen, reduce acidity and predispose to infection. Before menarche and after menopause, the vaginal pH varies between 6 and 7. Because of scant nerve endings in the vagina, the patient usually does not have symptoms until both the vagina and vulva are involved in an inflammatory or irritant process.

Vulvovaginal inflammation is the most common gynecologic disorder in prepubertal girls and includes both infectious causes (e.g., bacterial, fungal, pinworm) and noninfectious causes (e.g., contact/irritant, lichen sclerosis, foreign body). Factors thought to contribute to vaginitis in prepubertal females include less protective covering of the vestibule by the labia minora, low estrogen concentration resulting in a thinner epithelium, exposure to chemical irritants such as bubble bath, poor hygiene, front-to-back wiping and the short distance between the vagina and anus, foreign bodies, chronic medical conditions (eczema, seborrhea, and other chronic diseases), and sexual abuse. Infectious causes include respiratory and enteric bacterial organisms such as Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, group A streptococci and Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Shigella flexneri, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Chlamydia, as well as Candida and pinworms. Infectious causes may be more common in adolescents, especially those who are sexually active.4

GENERAL APPROACH

Obtain a detailed gynecologic history and perform a pelvic examination. History should include details of vaginal discharge, odor, irritation, itching, burning, bleeding, dysuria, and dyspareunia. Inquire about associated abdominal pain, new sexual partners, use of barrier protection during intercourse, relationship of symptoms to menses, use of antibiotics and contraceptives, and hygiene practices. Note the presence of vulvar edema or erythema, vaginal discharge, cervical inflammation, and abdominal and cervical motion tenderness.

During speculum examination, obtain a swab of the discharge and test for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection. If a patient refuses pelvic examination or it is not feasible, the patient may submit a self-swab of vaginal secretions or a urine sample.9

Microscopic examination of secretions and evaluation of pH are useful diagnostic tools. However, microscopes and reagents are not available in all EDs, microscopic examination is time consuming and tedious, and results depend on operator skill. To test pH, obtain a sample from the mid portion of the vaginal sidewall to avoid false elevations in pH caused by mucus. Sampling from the posterior fornix may yield inaccurate results because cervical mucus, blood, semen, douches, and vaginal medications can elevate the pH. Microscopic evaluation of fresh vaginal secretions using both normal saline solution and 10% potassium hydroxide slide preparation and fishy odor on whiff test help provide evidence for a diagnosis10 (Tables 102-2 and 102-3). Signs of vulvar inflammation and minimal discharge suggest the possibility of mechanical, chemical, allergic, or other noninfectious causes of vulvovaginitis.

| Test | Finding | Diagnosis | Comments13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 4.0–4.5 | Normal | — |

| 4.0–4.5 | Candidiasis | If undiagnosed after pelvic examination and evaluation of wet mount, treatment with a single dose of fluconazole is cost effective, but also test for Neisseria and Chlamydia. | |

| >4.5 | Bacterial vaginosis | If undiagnosed after pelvic examination and evaluation of wet mount, treatment with 2 grams of metronidazole ± a single dose of fluconazole is cost effective, but also test for Neisseria and Chlamydia. | |

| >4.5 | Trichomoniasis | If undiagnosed after pelvic examination and evaluation of wet mount, treatment with 2 grams of metronidazole ± a single dose of fluconazole is cost effective, but also test for Neisseria and Chlamydia. | |

| Microscopy of specimen prepared with normal saline solution | Clue cells | Bacterial vaginosis | — |

| Motile trichomonads | Trichomoniasis | — | |

| Pseudohyphae and/or buds | Candidiasis | — | |

| Whiff test of swab specimen prepared with potassium hydroxide | Fishy odor | Bacterial vaginosis | — |

| Microscopy of specimen prepared with potassium hydroxide | Pseudohyphae and/or buds | Candidiasis | — |

BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS

Bacterial vaginosis is the most common cause of vaginitis and accounts for up to 50% of cases in acutely symptomatic women. However, up to 50% of women who meet clinical criteria for this diagnosis are asymptomatic.

Bacterial vaginosis is a polymicrobial infection that occurs when the normal hydrogen peroxide–producing lactobacilli are replaced by other species including Gardnerella vaginalis, Ureaplasma, Mycoplasma, and various anaerobes. Risk factors include multiple sexual partners, intercourse with an uncircumcised male partner, vaginal intercourse immediately after receptive anal intercourse, lack of condom use, douching, and absence of peroxide-producing lactobacilli in the vaginal flora.1,11 Women who have never been sexually active are less commonly affected. Bacterial vaginosis is not classified as a sexually transmitted infection, but it is generally agreed upon that sexual activity plays a role in transmission and may promote infection.12

The most common clinical presentation of women with bacterial vaginosis is vaginal discharge and odor. Classically, a thin, whitish-gray discharge is present, generally with an increase in discharge volume. The absence of discharge or the presence of only a mild discharge makes the diagnosis less likely. When an odor is present, it may be described as a fishy smell. Introital or vaginal irritation, such as redness, tissue fissures, excoriations, or edema, is not common with bacterial vaginosis.

The diagnosis is based on history, speculum vaginal examination, microscopic evaluation of vaginal secretions, and point-of-care testing. Obtain secretions from the mid sidewall of the vagina, and mix with one to two drops of 0.9% normal saline. Cover with a coverslip for microscopic evaluation for clue cells; to check for fishy or amine odor, add one drop of 10% potassium hydroxide and assess vapors for fishy (amine) smell (see additional methods for amine testing below). To check pH, apply a small amount of secretions directly onto pH paper. The presence of three of the following four criteria makes the diagnosis:

A thin, homogeneous vaginal discharge

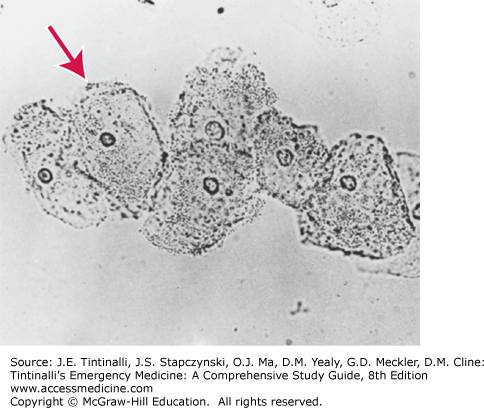

More than 20% clue cells on a wet mount (Figure 102-1)

Positive results on test for amine release, or whiff test

A vaginal pH level >4.5

The criterion with the highest sensitivity (89%) is vaginal pH, whereas that with the highest specificity (93%) is the amine odor, or positive result on whiff test. If vaginal pH is >4.5 and there is an amine odor, the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis can be made with confidence.14 A colorimetric card test for bacterial vaginosis detects a vaginal pH of ≥4.7 and volatile vaginal fluid amines. Commercially available tests that might be useful for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis include card tests for proline aminopeptidase (Pip Activity TestCard; Quidel, San Diego, CA), a DNA probe–based test for high concentrations of G. vaginalis (Affirm VP III; Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD), and the OSOM BVBlue test (Sekisui Diagnostics, Lexington, MA), all of which have performance characteristics that are comparable to Gram stain. Cards are available for the detection of elevated pH and trimethylamine; however, they have a low sensitivity and specificity and thus are no longer recommended. Cultures of vaginal discharge are not beneficial, because Gardnerella organisms are part of the normal vaginal flora. Polymerase chain reaction for various organisms is being used in research but is not clinically relevant at this time.1

The combination of bacterial vaginosis and leukorrhea (more WBCs than epithelial cells seen on a wet mount) is associated with a positive test result for Chlamydia (odds ratio = 3.8).15 For this reason, women who complain of vaginal discharge should be screened for and, depending on clinical suspicion, treated presumptively for N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia infection at the initial visit (Table 102-2). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also recommends syphilis testing for women engaged in high-risk sexual behavior, such as those having multiple sexual partners or a new sexual partner or engaging in unprotected intercourse. Finally, women of childbearing age should be screened for pregnancy, because this may impact medical treatment.

Recommended treatment regimens are listed in Table 102-4. The use of Lactobacillus intravaginal suppositories and probiotics to restore the normal vaginal flora is an ongoing area of research. Treating male sexual partners is not beneficial for preventing recurrence, but consider treating female partners, particularly with frequent recurrences, because bacterial vaginosis can spread between female partners.2 Counsel patients receiving metronidazole against consuming alcoholic beverages during the treatment period and for the following 24 hours to avoid a disulfiram-like reaction. Advise patients to refrain from intercourse or to use condoms during treatment.1

| Agent | Dosage |

|---|---|

| Recommended Regimens | |

| Metronidazole* | 500 milligrams PO twice a day for 7 d |

| Clindamycin cream 2% | One full applicator intravaginally every night for 7 d |

| Metronidazole gel 0.75% | One full applicator intravaginally once a day for 5 d |

| Alternative Regimens | |

| Clindamycin | 300 milligrams PO twice a day for 7 d |

| Clindamycin ovules | 100 milligrams intravaginally every night for 3 d |

| Tinidazole | 2 grams PO daily for 2 d |

| Tinidazole | 1 gram PO daily for 5 d |

| Regimens for Pregnant Women | |

| Metronidazole* | 250 milligrams PO three times a day for 7 d |

| Metronidazole* | 500 milligrams PO twice a day for 7 d |

| Clindamycin | 300 milligrams PO twice a day for 7 d |

Overall cure rates 4 weeks after treatment do not differ significantly for a 7-day regimen of oral metronidazole, metronidazole vaginal gel, and clindamycin vaginal cream. Metronidazole vaginal gel has fewer side effects (i.e., GI disturbance and unpleasant taste) but should not be used in women who are allergic to the oral preparation.

Recurrence of symptoms is seen within 3 months in 30% of treated patients who initially show a response. The reasons for this are unclear but could be from sexual transmission.15 Metronidazole gel 0.75% twice weekly for 4 to 6 months prevents recurrence.1

Bacterial vaginosis has been associated with several adverse health outcomes, including facilitation of co-infection with sexually transmitted infections such as human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus-2, Chlamydia trachomatis, and N. gonorrhoeae by decreasing local secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor levels.1,12 Bacterial vaginosis is also linked to complications related to pregnancy and surgical procedures, such as spontaneous abortion, premature rupture of membranes, amniotic fluid infection, chorioamnionitis, preterm delivery, postpartum endometritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, postoperative wound infection, and infection after vaginal and abdominal hysterectomy.16

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends treating all symptomatic pregnant women. Recommended treatment regimens are listed in Table 102-4. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention no longer recommends routine screening of asymptomatic pregnant women.1 Pregnant women who are at high risk for preterm labor should be considered for treatment to avoid preterm labor and other adverse outcomes of pregnancy.5 However, studies have not been able to demonstrate clear benefit in preventing adverse outcomes of pregnancy.1,17,18,19 Topical clindamycin preparations should not be used in the second half of pregnancy because of an increased association of adverse events, including low infant birth weight and neonatal infections.

CANDIDA VAGINITIS

Candida species are the second most common cause of infectious vaginitis.20 Prevalence data for vulvovaginal candidiasis vary because the disease is not reportable, many women self-medicate with over-the-counter preparations, and as many as half the women in whom candidiasis is diagnosed also have other conditions.20 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 75% of women will have at least one episode of vulvovaginal candidiasis in their lifetime.1

The organism is isolated in up to 20% of asymptomatic, healthy women of childbearing age, some of whom are celibate. Some women remain entirely asymptomatic despite being heavily colonized with Candida species.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is rare in nonestrogenized premenarchal girls but does occur and is common under 2 years of age. Consider undiagnosed juvenile diabetes or other forms of immunosuppression if Candida is diagnosed in a toilet-trained child.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree