Introduction

The vulva has received relatively little focus in the medical literature and has been referred to as “the forgotten pelvic organ” [1]. There are many ways in which the keratinized skin and mucocutaneous surfaces of the vulva differ from the skin on the rest of the body. It is the only area of the human body where epithelium from all three embryologic layers coalesce. In addition, the vulvovaginal tract encounters foreign proteins and antigens necessary for reproduction, and has evolved with a unique immunologic response [2]. Lastly, the subcutaneous tissue of the labia majora is looser, allowing for considerable edema to form. Vulvar dermatoses may present in a variety of ways, ranging from asymptomatic to mildly bothersome to severely disabling. Vulvar dermatoses are often difficult to treat and severely impact a woman’s quality of life. Vulvar dermatoses may present with dyspareunia. Symptoms may include sexual pain, nonsexual pain, itching, fissuring, and postcoital bleeding. Women may be embarrassed by the disfiguring vulvar changes that may occur and avoid sexual intimacy. Patients are frequently reticent to discuss their symptoms with a health care provider, and many clinicians feel challenged with respect to the management of vulvar disease. These factors may result in women receiving suboptimal treatment, resulting in persistent symptoms and/or avoidance of sexual relationships altogether. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the diagnosis and treatment of the vulvar dermatologic conditions that may be associated with dyspareunia.

The vulva should be examined with a vulvoscope as it allows the clinician to see the disease process in greater detail, aiding in an accurate diagnosis (see Chapter 7). Digital photography is especially useful for documenting baseline findings, progress with treatment, and educating the patient. The vulvar examination should begin with the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position. Specifically, the vulva should be thoroughly examined for erythema, atrophy, induration, fissures, lichenification, ulceration, erosions, hypopigmentation, scarring, phimosis of the clitoris, narrowing of the introitus, and tenderness to palpation. A speculum exam should also be performed to look for ulcerations or synechiae in the vagina.

A vulvar biopsy is strongly recommended whenever abnormalities are seen on vulvoscopy. A 4- or 5-mm punch biopsy should be performed under local anesthesia (lidocaine with epinephrine), and the biopsy site can be closed with one or two stitches of absorbable suture such as 4.0 Vicryl-Rapide (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ). A biopsy is extremely useful in differentiating many dermatologic disorders that can present in similar ways. Working with an experienced dermatopathologist can help ensure the accuracy of biopsy results.

The following dermatoses are commonly encountered when treating women with dyspareunia.

Lichen Sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic, lymphocyte-mediated cutaneous disorder affecting approximately one in seventy women [3]. There is a bimodal peaked incidence in premenarchal girls and menopausal women with the average age of diagnosis being 51 years. Extragenital lesions may occur in 11% of female patients [4]. While the etiology has not been completely elucidated, LS is most likely an autoimmune disorder as it is associated with other autoimmune disorders including autoimmune thyroid disease, alopecia areata, vitiligo, pernicious anemia, and lichen planus [5–7]. In addition, there are high levels of circulating autoimmune antibodies in patients with LS. A genetic susceptibility to LS has been suggested because of reports of familial association. In addition, several studies have demonstrated increased prevalence in women with specific major histocompatability complex (HLA-complex) subgroups such as HLA-DQ7 [8]. Women with LS have a 4–5% risk of developing vulvar carcinoma [5]. LS has been found in greater than 60% of cases of squamous carcinoma of the vulva [9].

Clinically, while some patients are asymptomatic, most give a history of pruritis or pain [3]. One study that focused on the impact of lichen sclerosus on a woman’s sexual satisfaction showed that women with LS were less likely to be sexually active (vaginal intercourse, oral intercourse, and masturbation) than control groups. Furthermore,79% of women with LS reported chronic vulvar pain [10]. In another study by Dalziel, 76% of women with LS had dyspareunia and more than half of those women were completely apareunic because of LS [11].

Physical examination reveals white atrophic plaques (“cigarette paper”), depigmentation, ecchymoses, resorption of the labia, narrowing of the introitus, and distortion of the vulvar architecture (Figure 9.1). Lichen sclerosus may involve the labia minora and inner portion of the labia majora, interlabial sulcus, clitoris, vestibule, perineum, and the perianal region, but almost never involves the vaginal mucosa. Scarring of the clitoral prepuce may cause “phimosis” of the glans clitoris, which in turn, can lead to formation of a smegmatic psuedocyst abscess between the prepuce and clitoris [12].

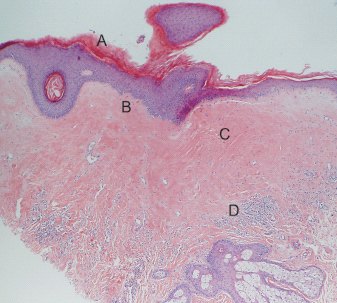

A biopsy specimen should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis because the histopathologic changes of LS are distinctive. Characteristic pathologic findings include hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, epidermal atrophy with loss of rete ridges, homogenization of the collagen in the upper dermis, and a lichenoid (bandlike) inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 9.2). It is essential to obtain the biopsy prior to starting treatment because the pathognomonic changes described above can resolve with the application of corticosteroids [13].

The gold standard treatment for LS is an ultrapotent topical corticosteroid ointment, such as clobetasol propionate ointment, applied daily until all active disease has resolved [8]. More recently, tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, topical calcineurin inhibitors, have been described for the treatment of LS [14–16]. The potential advantage of these newer medications is they do not inhibit collagen synthesis so they do not cause dermal atrophy. Areas of ulceration or lichenification that do not resolve after adequate treatment must be biopsied to rule out vulvar intraep-ithelial neoplasia or carcinoma. After all active disease has resolved, patients may taper the frequency of treatment to twice per week. Patients should be counseled that LS is a chronic disease and that treatment only when symptomatic is not sufficient because there can be active disease without symptoms. Lastly, it should be noted that topical testosterone was historically used to treat LS, but controlled trials in the 1990s showed that this is an ineffective treatment [17].

Figure 9.2 Histology of lichen sclerosus. (a) Hyperkeratosis of the epidermis. (b) Epidermal atrophy with loss of rete ridges. (c) Homogenization of the collagen in the upper dermis. (d) Lichenoid infiltrate in the dermis.

In the past, surgery for lichen sclerosus was reserved for patients in whom there was associated high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia or carcinoma [18]. Surgery to correct architectural changes such as narrowing of the introitus or clitoral phimosis was contraindicated because of a process known as the koebner phenomenon. Koebnerization in LS is a pathological process in which normal skin becomes sclerotic after it is injured or traumatized [19]. However, koebnerization in women with LS can now be effectively prevented with ultrapotent corticosteroids. Perineoplasty has been shown to improve dyspareunia in 90% of women who had introital stenosis because of LS [4]. In addition, surgery to correct clitoral phimosis has been shown to improve clitoral sensation and increase orgasms in women with LS [12].

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus (LP) is an intensely inflammatory, autoimmune, mucocutaneous disorder that may involve both keratinized skin and mucosal surfaces. In addition to affecting keratinized skin of the trunk and extremities, LP often affects the oral and vulvovaginal mucosae [20]. Vulvovaginal involvement can be associated with dyspareunia, itching, burning, pain, and destruction of the vulvar and vaginal architecture [21]. Approximately 1 in 400 women have vulvovaginal LP [22]. However, the true incidence of LP is difficult to assess because patients may present to a wide variety of specialists including dentists, dermatologists, gynecologists, and gastroenterologists [22]. The age of peak prevalence ranges from ages 30 to 60 years [23].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree