Introduction

A number of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are associated with sexual pain in women, and we will discuss these under the headings of superficial and deep dyspare-unia. In particular, ulcerative disease, vaginal discharges and vulvovaginitis, (see Chapter 15), and pelvic pain will be reviewed. In addition to dyspareunia, patient concerns about STIs include health anxieties about HIV, stigma, shame, and fertility issues [1]. Women with STIs are at significantly increased risk of transmitting and acquiring HIV and, surprisingly, may continue to have unprotected sex in spite of any symptoms including pain [2]. Treatment of the STIs, whether in syndromic fashion [3] or based on laboratory diagnosis, not only resolves pain but also decreases HIV transmission [4, 5].

Ulcerative Disease

Genital Herpes

Genital herpes (GH) is usually caused by herpes simplex type 2 (HSV-2), but herpes simplex type 1 (HSV-1) is an increasingly common isolate in the United States, probably as a result of lower rates of nonsexual acquisition of oral HSV in childhood and adolescence [6]. HSV-1 and HSV-2 are genotypically and phenotypically very similar, but can be distinguished serologically [7]. In a recent survey, 17% of the United States population ages 14–49 showed positive-type specific antibody to type-2 herpes simplex [6]. Apart from causing local pain and dyspareunia, GH may cause marked psychological distress [8].

Viropathology

The virus gains entry into the genital mucosa by binding to the host cell surface. Molecular motor proteins then transport HSV up the sensory nerve fibers to the dorsal root ganglion [9] where latency is established. Reactivation results in transportation of virus back down the peripheral nerves to the skin and mucosa where typical lesions develop (not necessarily ending up in the site of initial entry). In many cases, the precipitating factors for reactivation cannot be identified, but local trauma (including sexual activity), dermatoses, fevers, and immunosuppression may initiate this event.

Clinical Presentations

Epidemiological studies suggest that as many as 90% of those who have type-specific antibodies to HSV-2 have never knowingly suffered a clinical outbreak [10]. However, in those individuals who are symptomatic, pain is an important symptom. Symptoms are more severe in a primary HSV-2 or HSV-1 infected woman who has not had HSV-1 in the past [11]. Clinically, primary HSV-1 and HSV-2 are indistinguishable. Fever, headache, malaise, and myalgia are reported in up to 70% of women with primary HSV-2 and appear in the first few days of the illness [12].

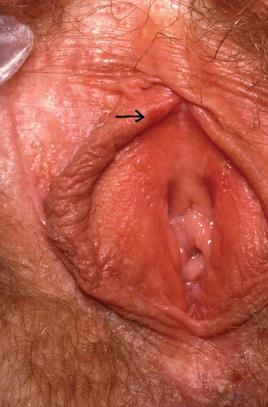

Classically, the lesions progress from erythematous papules, to vesicles, pustules, and then painful ulcers, which can coalesce (Figure 11.1). On moist mucosal surfaces they appear as ulcers without forming crusts as they would in the outer skin of the labia majora. Symptomatic lesions can appear anywhere on the genitalia from the introitus out to the upper thighs, perianal area, and buttocks [11]. Pain from these lesions may be severe and constant, with exacerbation at micturition and defecation if lesions are in the periurethral or perianal area, respectively. Untreated patients can develop new crops of lesions with pain persisting for up to 3–4 weeks [11]. Other complications of primary GH are acute urinary retention, sacral neuropathy, and meningitis.

About 25% of patients with a first clinical episode of HSV-2 have a mild clinical picture rather like that of a recurrence. These patients have preexisting HSV-2 antibodies, implying that they may not have acquired the infection from a recent partner [13].

Recurrences of GH are less common when the primary outbreak was with HSV-1 [14]. HSV-2 tends to recur sooner if the primary episode was prolonged, and 86% of women will have at least one recurrence after a year [15]. Recent data suggests that in the ensuing years, recurrence rates gradually decrease in most patients [16]. The lesions in recurrent GH tend to be fewer in number and less painful than first episodes with an average healing time of 5–10 days (Figure 11.2).

A proportion of patients exhibit a prodrome that usually manifests as itching, tingling, or pain in the sacral dermatomes or more specifically, in the area where the outbreak is about to appear. Some patients complain of a low mood at this time, which may be related to systemic cytokine release affecting their psychological state [8].

Atypical presentations include fissuring in genital dermatoses and postmenopausal atrophic genital mucosa. Similar lesions may occur in healthy mucosa where the woman has genital arousal problems and is thus poorly lubricated. Some patients are quite severely psychologically disabled by recurrences of GH, often because of issues of poor self-esteem, reactive depression, and disclosure issues [17].

Diagnostic Testing

The clinical features of GH should strongly suggest the diagnosis. However, the diagnosis should be confirmed by testing the lesional material by viral tissue culture. This is about 80% sensitive in primary outbreaks and 50% in recurrent lesions [14]. Antibody staining will determine if the isolate is HSV-1 or HSV-2. The newer the lesional material (e.g., vesicles or pustules), the less likely there will be a false negative result.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is up to four times more sensitive than culture and is being increasingly used by local hospital laboratories [18]. When local tests are negative, type-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) testing of serum directed against glycoprotein G can be undertaken. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has licensed four such kits [19]. Clinical judgment is needed to ensure that a positive result relates to any clinical pathology.

Treatment

Antiviral agents underpin the treatment of GH. In primary and recurrent GH, the aims are to reduce viral reproduction, shorten time to healing, and decrease pain. The specific antivirals (aciclovir, valaciclovir, and famciclovir) and their dosing schedules are well presented in a recent paper [20]. Traditionally, suppressive therapy is given to women who have frequent recurrences. Their use has been shown to decrease rates of transmission of GH to partners [21]. Apart from antivirals, women should be counseled about the advantages of barrier contraception and the need to abstain from sex at the time of clinical outbreaks. Pain is best managed in the acute phase by the use of nonopiate analgesia and local anesthetic agents.

Other Less Common Ulcerative Disease

Ulcers may be caused by syphilis, chancroid, donovanosis, or lymphogranuloma venereum. An ulcer may contain more than one pathogen, and all of these conditions may enhance HIV transmission.

Syphilis

Syphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum. In the adult with ulcerative disease in North America, it is always acquired sexually. The average time to the appearance of a primary syphilitic ulcer or chancre is 3 weeks (9–90 days). The chancre is characteristically painless and indurated, but it can be painful and tender and may appear anywhere on the genital area. There is usually nontender local lymphadenopathy. Secondary syphilis usually commences 4–10 weeks after the appearance of the chancre and may cause, amongst its many other features, condylomata lata, which may be tender and appear as de-epithelialized genital warts [22]. Diagnosis by the nonspecialist is made by serology.

Chancroid

This condition is not common in North America. The combination of a painful genital ulcer and tender suppurative local lymphadenopathy should suggest chancroid, particularly if tests for syphilis and GH are negative. Laboratory diagnosis relies on special culture medium. No FDA-approved PCR tests are currently available.

Lymphogranuloma Venereum (LGV)

This is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis serovars L1-3. The most common clinical manifestation is tender inguinal and/or femoral lymphadenopathy (rarely with a “groove” between them). However, a tender genital ulcerat the site of inoculation may be present transiently. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) of ulcer or lymph node material are usually diagnostic. Very rarely, LGV causes vulvar elephantiasis [23].

Vaginal Discharge and Vulvovaginitis

Trichomoniasis

Trichomoniasis (TV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide. It is caused by a flagellated protozoan called Trichomoniasis vaginalis, which can infect the vagina, urethra, Skene’s glands, and Bartholins glands [24–31]. Women with TV usually complain of a vaginal discharge (>50%) [32], vulvar itching, or dysuria [33], but some may be asymptomatic [34]. The vaginal discharge is classically frothy yellow-greenish (10–30%) but can vary in color and consistency and may indeed look normal [34]. Evidence of vulvitis or vaginitis is also common.

Diagnosis is usually made on microscopy of a sample from the posterior fornix; however, the sensitivity of this test is only 60–70% [5]. The gold standard test is still culture [35], although polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests are being developed that are thought to be highly reliable (none approved by the FDA to date) [5, 36]. In-office rapid immunochromatographic assays for TV have recently become available.

Because TV commonly infects the uterine cavity, urethra, and paravaginal glands, it is imperative to give systemic medication. Cure rates with oral metronidazole are in the order of 90–95% [5]. True treatment failure is rare; however poor compliance with medication or re-infection is more common. Expert guidance should be sought in true treatment failure [5].

TV in pregnancy is associated with preterm labor and low birth weight. TV in a woman with HIV may increase her risk of transmitting HIV to a sexual partner or contracting HIV if exposed [37].

Partners should be screened and treated for TV. Follow-up is only necessary for women who remain symptomatic despite treatment [5].

Sexually Transmitted Causes of Pelvic Pain and Deep Dyspareunia

Acute Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) and Its Complications

Introduction

PID is a condition characterized by endometriosis, parametritis, salpingitis, tuboovarian abscess, and pelvic peritonitis. Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhea (NG) ascend from the vagina and cervix to the upper genital tract [38]. PID can vary greatly in severity from asymptomatic to generalised peritonitis and death (very rare). Indeed, many episodes are likely to go unnoticed, undiagnosed, or misdiagnosed due to the mild or nonspecific nature of the woman’s symptoms. However, PID is a significant burden both to women’s heath and the economy. In the United States alone, it is estimated that every year over 1 million women have an episode of acute PID with more than 100,000 cases of subfertility occurring annually due to this condition. The average per person-lifetime cost of PID may be as high as $318,000 [39]. PID is an extremely important cause of preventable morbidity, particularly, reproductive ill health [40].

Both Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea have been proven as causal agents in PID [41]. The rates of both these infections continue to rise, particularly in the young, with the highest rates in the 15–19 age group. CT infections are more common than NG infections, and are the most common cause of PID in the United States, accounting for nearly 40% of all cases. The incidence of PID in women with untreated or inadequately treated CT can vary from 10% to 80% [42], but others feel the true rate is uncertain [43].

Not all women with an STI in the lower genital tract develop PID; host susceptibility may be genetically determined [44]. PID caused by NG is often more acute and severe in its presentation, but it is less likely to cause longterm sequelae when compared with chlamydial PID.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree