Introduction

A variety of vaginal disorders, some infectious, others noninfectious, cause dyspareunia. This chapter reviews the two most common causes of noninfectious vaginitis— atrophic vaginitis and desquamative inflammatory vaginitis (DIV.)

Vaginal Atrophy and atrophic Vaginitis

While dyspareunia affects 10–15% of premenopausal women, it is a presenting complaint in up to 39% of postmen opausal women [1]. In postmenopausal women, dyspareunia is attributed mainly to dryness resulting from vaginal atrophy. atrophic vaginitis, denned here as symptomatic vaginal atrophy, is believed to be the most common cause of vulvovaginal symptoms in menopausal women and affects 10^0% [2]. However, only about 25% of symptomatic patients seek medical help.

Etiology of Vaginal Atrophy

Vaginal atrophy results from inadequate estrogen levels in the vagina. This occurs most commonly with menopause and aging, but can result in younger women due to hypothalamic amenorrhea, hyperprolactinemia, lactation, and usage of antiestrogenic medications [2]. Occasionally, usage of extra-low dose contraceptive pills [1] and cancer therapy [2] may cause similar symptoms.

During the reproductive years, estrogen plays a major role in maintaining the normal vaginal environment. This includes a thickened, rugated vaginal surface, increased blood flow and lubrication, lactobacillus-dominant flora, and alow (< 4.5) pH [2,3]. With estrogen withdrawal during menopause, significant changes occur in the vagina, resulting in the tissue becoming pale, thin, and less flexible. Blood flow diminishes, secretions decrease, and pH increases [2,3]. Vaginal flora changes from a lactobacillus-dominant flora to one with primarily anaerobic gram-negative rods and gram-positive cocci [4]. These changes may affect a woman’s well-being, particularly when it comes to sexual activity.

Although all menopausal women undergo the same hormonal changes, only 10–0% of them will become symptomatic. There is limited ability to predict which women will develop symptoms [2]. The effect of estradiol on the vagina at the molecular level was recently studied [5] : differentially expressed mRNA transcripts in vaginal biopsies were determined by microarray analysis in women with vaginal atrophy before and after estra-diol treatment. This study found evidence for estrogenmediated regulation of over 3,000 genes involved in vaginaltissue remodeling. It is possible that the variation in vaginal symptoms between menopausal women may result from genetic polymorphisms that mediate processes such as estrogen metabolism and expression of estrogen receptors in this tissue.

Sexual Dysfunction in Vaginal Atrophy

Data from the Yale Midlife Study indicated that 77% of menopausal women reported loss of sex drive, 58% had vaginal dryness, and 39% suffered from dyspareunia [6]. The physiological changes occurring in vaginal atrophy expose menopausal women to potential dyspareunia in several ways. Vaginal dryness causes increased friction during intercourse. The thin vaginal walls are friable and become prone to mechanical damage and formation of petechiae, ulcérations, and tears with sexual activity. With long-standing estrogen deficiency, the vagina may become shorter, narrower, and less elastic. All of these changes increase the likelihood of trauma, infection, and pain. Furthermore, changes occurring with aging, such as subcutaneous fat loss and decreased skin lipid production, can result in slower healing after injury. Lastly, age-dependent hypotonia or hypertonia of the pelvic floor muscles can also contribute to dyspareunia [7].

In addition to the physical changes occurring with estrogen depletion, sexual dysfunction in this population is influenced by the coexistence of decreased libido, decreased sexual arousal, and psychosocial factors. In general, premenopausal women have enough lubricationand, even in the absence of arousal, can accommodate vaginal penetration without pain [ 1 ]. In contrast, vaginal engorgement and lubrication that accompanies sexual arousal may be decreased in patients with vaginal atrophy [8].

In postmenopausal women, dyspareunia may result from a pre existing arousal disorder that was unidentified until “unmasked” by estrogen depletion [8]. Psychosocial factors in this age group, including depression, anxiety, partner disability, poor overall health, and changes in social status, can contribute to dyspareunia [7]. Avoidance of intercourse by symptomatic women may further contribute to vaginal shrinkage and loss of elasticity, which in turn can lead to additional barriers to future acts of sexual intimacy. Thus, it is essential that health care providers address both physiologic and psychological factors when treating patients with vaginal atrophy and sexual dysfunction.

Diagnosis of atrophic Vaginitis

Patients with atrophic vaginitis may complain of vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, itching, discharge, pain [2], and irritative urinary symptoms. Symptoms are usually progressive and do not resolve spontaneously [2]. Although secretions are typically decreased, patients may note an abnormal yellow or watery discharge [3]. Vaginal bleeding may occur with severe atrophy [2].

Signs vary with the degree of atrophy. Loss of connective tissue substance results in shrinkage of the labia majora. The labia minora may disappear completely, and the introital opening is often diminished. The vagina has a pale, dry, nonrugated appearance, and submucosal petechial hemorrhages may be visualized [9]. The vaginal dimensions decrease, and the fornices may become obliterated, making the cervix flush with the vault [2, 9].

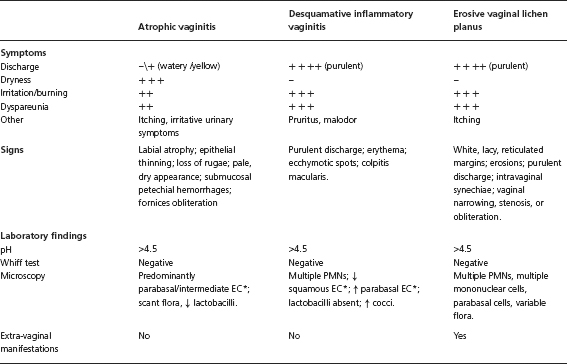

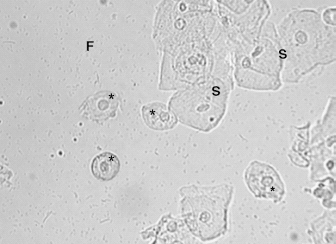

In general, the diagnosis is made by identifying characteristics changes on physical examination, noting an elevated vaginal pH, and finding parabasal cells on saline microscopy (Figure 16.1 and Table 16.1). Interestingly, the degree of atrophic changes as measured by microscopy does not correlate with symptoms [10]. Unfortunately, measuring serum estrogen levels does not aid in the diagnosis of atrophic vaginitis. Although the findings above establish an accurate diagnosis, symptoms alone dictate the need for treatment.

Figure 16.1 Microscopic findings in atrophic vaginitis. Normal superficial cells (S) are replaced by parabasa cells (*), which are smaller, rounder, and have a large nucleus. Vaginal flora (F) is scant, with a relative absence of lactobacilli. A maturation index, where a cytopathologist quantifies the percentage of immature vaginal epithelial cells, can aid in the diagnosis if a provider is unable to recognize intermediate and parabasal cells.

* EC-epithelial cells; PMNs-polymorphonuclear leukocytes

Treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree