Vascular Access

Eric F. Reichman

The practice of emergency medicine frequently requires access to the venous and sometimes the arterial circulation of a patient (1). Vascular access allows for blood sampling, medication administration, blood product administration, hydration, patient monitoring (i.e., arterial lines and pulmonary artery catheters), and insertion of cardiac pacing wires. Peripheral venous puncture is the most common invasive procedure performed in the emergency department (ED). Peripheral vein cannulation is performed on a daily basis and is the cornerstone of circulatory resuscitation.

There are many techniques with which to access a patient’s venous or arterial circulation. Venous puncture (venipuncture) or arterial puncture with a needle is only indicated for the sampling of blood. Medications may be administered as a one-time dose via this technique, but the risk of extravasation is high. Venous cannulation (intravenous [IV] placement) is indicated for repeated sampling of venous blood. Venous cannulation is also performed for the administration of medications, fluid solutions, blood products, and nutritional support.

There are some general contraindications to peripheral vascular access. Arteries and veins should not be accessed through infected skin. Do not withdraw venous blood from a vein proximal to a running IV infusion. The blood sample will be tainted or diluted by the infused solution. A hole in the vein may allow blood, infused solutions, and medications to extravasate into the surrounding tissues. Venipuncture and venous cannulation of veins in an extremity with an arteriovenous fistula should be avoided. Veins in the upper extremity that may be needed for arteriovenous fistula construction for hemodialysis in the future should not be punctured unless absolutely necessary.

Complications specific to each technique and site are discussed more fully in this chapter. Venous and arterial catheters should be assessed immediately after their placement and be reassessed frequently. The assessment must include the skin puncture site, catheter function, the neurovascular status of the distal extremity, and the patient’s overall condition.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR INTRAVENOUS ACCESS

Although veins can dilate and constrict somewhat on their own, they do so mostly in response to the pressure within them. The use of venous tourniquets, dependent positioning, “pumping” via muscle contraction, and the local application of heat or nitroglycerin ointment all contribute to venous engorgement. These maneuvers can be used to aid in the performance of a venipuncture or peripheral venous access.

The vascular anatomy can affect access (2). Deficient perivascular connective tissue permits the vein to “roll” from side to side and evade the needle. Tough connective tissue can impede the entry of a flexible catheter while serving to stabilize the vein and prevent its collapse. Venous valves allow unidirectional flow and prevent blood from pooling in the dependent portions of the extremities. Valves can block the passage of a catheter through and into a vein. Valves are more numerous at the points where tributaries join larger veins and in the lower extremities. Valves are almost absent within the large central veins, the veins of the head, and the veins of the neck.

Peripheral veins are easiest to access at the apex of the “Y,” formed when two tributaries merge into a larger vein or where the vein is straight and free of branches and valves for two or so proximal to the site of puncture. These sites tend to be anchored and “roll” less than other sites.

The angle of insertion of the needle varies depending on the depth of the vein being punctured. A shallow angle (30 to 45 degrees) should be used for small and superficial veins. A more obtuse angle (60 degrees) should be used to access deeper veins. Very small and superficial veins should be entered at a very acute angle (15 to 30 degrees).

Fluid Flow Considerations

Both the diameter and the length of the infusion device affect the flow rate through the catheter. Viscous fluids (e.g., blood products and albumin) infuse more slowly than less viscous fluids (e.g., saline). These relationships can be seen in the solution of Poiseuille equation for ideal fluid flow through a cylindrical tube. The pressure gradient and resistance to flow is inversely proportional to the length of the catheter tubing. Flow rates decrease as catheter length increases. Using the shortest possible catheter permits the highest fluid infusion rates. Catheter diameter changes will have the most effect on flow rates. The flow rate increases to the fourth power as the catheter internal radius increases. Maximal flow rates result from using the largest bore or largest internal diameter (i.e., smallest gauge) catheter that will fit inside the vein. Large-bore venous catheters are preferred for high-volume infusions.

Venous Cannulation

There are four main techniques of venous cannulation (2). The first is the needle-only technique using a butterfly-type needle. This method is seldom used today. The catheter-over-the-needle is the most commonly used technique for peripheral venous cannulation. The catheter-through-the-needle technique is occasionally used but not very popular. The Seldinger wire-guided technique is most commonly used for central venous access.

Identify the vein to be cannulated and the site of the skin puncture. Clean the area of any dirt and debris. Cleanse the skin with isopropyl alcohol, chlorhexidine, or povidone iodine. Apply a tourniquet to the extremity, proximal to the venous cannulation site, to engorge the vein. Additional engorgement of the vein can be accomplished by placing the extremity in a dependent position, “pumping” via muscle contractions of the extremity, and the application of heat or nitroglycerin ointment over the vein. Optionally, a small subcutaneous wheal of local anesthetic solution may be placed at the skin puncture site to provide comfort to the patient.

The needle-only technique is used occasionally for short-term venous access in young children and elderly patients with fragile veins. This system is prone to malposition and infiltration. The tip of the needle can easily lacerate the vein if the needle is not secure and allowed to move. This technique is, therefore, recommended only for venous blood draws and not venous cannulation.

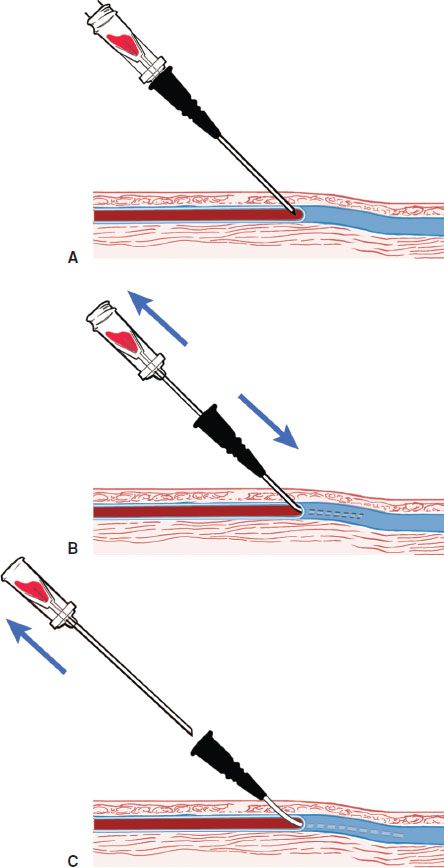

The catheter-over-the-needle systems are most commonly used for venous access (Fig. 5.1). The infusion catheter fits closely over a hypodermic needle. Placement of these catheters is usually quick and simple. Several considerations should always be kept in mind when using a catheter-over-the-needle. Intravascular placement is indicated by a flash of blood in the hub of the needle. If the patient’s venous pressure is very low or if the needle is long and narrow, both sides of the vessel may be traversed (through and through) before the practitioner realizes that the needle was within the vein. If the tip of the needle is withdrawn from the vein, the catheter will not advance. If the catheter is advanced when the tip of the needle but not the catheter is within the vein, the catheter will not advance. The catheter will push the vein off the needle. Depressing the skin just distal to the puncture site and pulling it distally can prevent the vein from “rolling.”

FIGURE 5.1 The catheter-over-the-needle technique. (Reprinted with permission from Reichman EF. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.)

As opposed to the over-the-needle approach, the catheter-through-the-needle technique eliminates the need for a needle that is as long as the catheter and eliminates the possibility of pushing the vein off the end of the needle when the catheter is advanced (2). The main disadvantage of this technique is the possibility of the needle tip shearing off the catheter, resulting in a catheter embolism. This complication is prevented by using proper technique. Another disadvantage is an increased risk of hematoma formation because the needle used for venipuncture must be larger in diameter than the catheter.

The Seldinger technique allows for the placement of a catheter over a wire rather than directly over a needle. The wire used must be longer than the catheter. The needle used to insert the wire can be short and of a smaller gauge than the catheter. The Seldinger technique is most commonly used for central venous catheter insertion.

VENIPUNCTURE AND PERIPHERAL INTRAVENOUS ACCESS

The upper extremity is preferred to the lower extremity for vein cannulation (3). Distal placement should be attempted before moving more proximal (3). Avoid veins overlying a joint. These simple principles allow the patient maximum mobility and increase the chance of successfully cannulating a vein. It is easiest to insert a venous cannula where two tributaries merge and form a “Y.” Choose a straight portion of vein without branches to minimize the chance of hitting valves within the vein and to make threading the catheter easier.

Peripheral Venipuncture

Stabilize the vein with the nondominant hand. Insert the needle attached to a syringe or vacuum tube adapter, with the bevel upward, into the vein at a 45- to 60-degree angle. Lower angles, at times nearly parallel to the skin, are often required to enter very narrow or superficial veins. Apply negative pressure to the syringe. A flashback of blood in the hub of the needle indicates that the tip of the needle is within the vein. Pulsatile blood indicates an arterial puncture. Unless venous blood is specifically needed for a test, collect the necessary samples before removing the needle. No additional harm will be done by withdrawing a blood sample from an artery that has already been punctured.

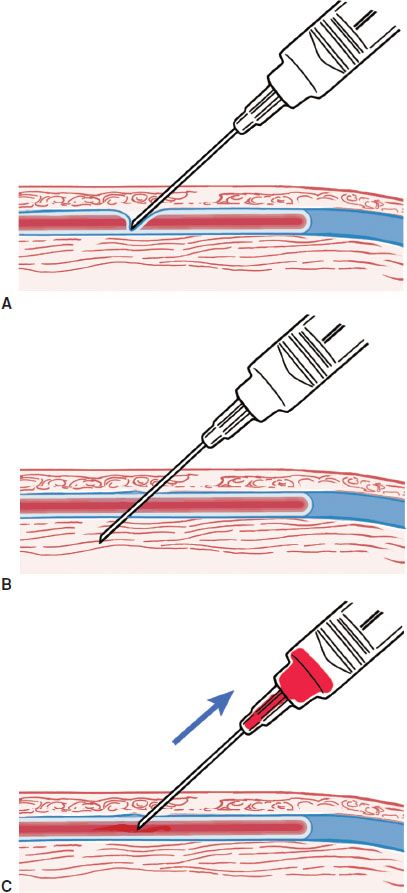

If no blood is obtained, slowly advance the needle until it is deeper than the judged depth of the vein. The tip of the needle can collapse the vein and prevent the flashback of blood (Fig. 5.2A). Slowly withdraw the needle to just beneath the skin. The vein will often have been punctured through-and-through (Fig. 5.2B). If this is the case, blood will flash back into the syringe as the needle is withdrawn (Fig. 5.2C). If no blood is obtained by the time the needle is withdrawn to just beneath the skin, redirect the needle, and make another attempt at puncturing the vein. Never sweep the point of the needle around without withdrawing it as the sharp bevel can lacerate nearby structures.

FIGURE 5.2 Through-and-through puncture of a vein. (Reprinted with permission from Reichman EF. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.)

Peripheral Intravenous Cannulation

Vein cannulation begins with a successful venipuncture (2). Insert the catheter-over-the-needle through the skin and into the vein (Fig. 5.1A). A flash of blood in the hub of the needle confirms that the tip of the needle is within the vein. Advance the catheter-over-the-needle an additional 2 to 3 mm to ensure that the catheter is within the vein. Securely hold the hub of the needle. Advance the catheter until its hub is against the skin (Fig. 5.1B). Withdraw the needle leaving the catheter in place (Fig. 5.1C). Apply pressure with the nondominant index finger over the catheter to prevent blood from exiting the catheter. Attach IV tubing to the catheter hub, and begin the infusion. Secure the catheter with tape.

A modified Seldinger technique (described later in this chapter) with a radial artery catheterization kit is very useful for deep brachial and external jugular venous catheterization (3). The depth of the deep brachial vein combined with overlying skin (which is often scarred from previous venous punctures) makes catheterization with the usual 1.25-in catheter difficult. The external jugular vein is quite mobile, and the overlying tissues are fairly tough. This combination can make threading an over-the-needle catheter into the vein, without pushing the vein off the end of the needle, quite difficult.

Pediatric Considerations

Venipuncture and peripheral venous access can be quite a challenge in the infant and small child (3). Proper restraint of the extremity will greatly aid the process. Aside from the techniques discussed above, there are a few techniques that can aid pediatric vascular access. The scalp veins can be used for venous access in newborns. Scalp veins are most easily cannulated with a small (23- to 25-gauge) butterfly needle or catheter. A rubber band can be placed about the baby’s head as a tourniquet. Other veins commonly used include those of the antecubital fossa, dorsal hand, dorsal foot, the external jugular vein, and the saphenous vein at the knee or groin. For small and superficial veins, place a small bend at the hub of the catheter-over-the-needle assembly. This bend provides a less-acute angle and easier entry into the vein. The best guide to the gauge (diameter) of catheter to use is to compare the catheter to the vein. The catheter should be at least slightly smaller than the vein. In practice, the smallest readily available catheters are 24 gauge. Keeping a peripheral IV line from being pulled out by an active toddler is quite a challenge. Each institution has its own “recipe” for securing pediatric IVs including taping securely, covering the catheter with a cut plastic medicine cup, and covering the whole assembly with a gauze roll or stockinette.

Assessment

The IV line should flush easily. Any infusions should flow by gravity alone. Progressive swelling at the catheterization site indicates a hematoma formation or extravasation of infused fluids. Peripheral infusions of vasopressors, IV contrast, and caustic solutions require the skin puncture site to be assessed frequently and carefully as extravasation may lead to extensive local soft tissue necrosis. Pain at the IV access site must be taken seriously and should prompt a search for the cause.

Complications

The main complications of venipuncture are pain and hematoma formation. Other complications include nerve injury and usually reversible paresthesias. Infection is uncommon from simple venous sampling. In addition to these complications, venous catheters have additional risks. IV catheters increase the risk of superficial venous thrombosis and thrombophlebitis. It is possible to injure a number of structures in the neck or cause a pneumothorax during external jugular vein cannulation with inadvertent deep penetration. Extravasation of some IV solutions can cause local skin necrosis. Extravasation of large volumes into a muscle compartment can lead to a compartment syndrome, although this is rare with superficial peripheral venous lines. Infections can often be prevented by using aseptic technique, using sterile dressings, and changing peripheral catheters every 48 to 72 hours. The rare complications of peripheral nerve palsies, pressure necrosis, and compromised peripheral circulation do occasionally occur. Complications can be prevented by making frequent neurovascular checks to any restrained extremity, padding all pressure points, and avoiding the placement of circumferential tape on an extremity.

CENTRAL VENOUS ACCESS

Percutaneous cannulation of the central veins is an essential technique for both long-term and emergent medical care (4). Access to the major veins of the torso allows rapid high-volume fluid resuscitation, administration of concentrated ionic and nutritional solutions, and hemodynamic measurements. The right internal jugular vein is generally preferred to the left internal jugular vein as the site of central venous cannulation. The right internal jugular vein provides a nearly straight and direct route to the superior vena cava. The dome of the right lung is somewhat lower than that of the left lung and thus decreases the chance of a pneumothorax during catheter placement. The thoracic duct is relatively large and lies high in the left chest. These anatomic considerations favor the right internal jugular approach to central venous cannulation to minimize complications.

The internal jugular route is acceptable for central venous access in most cases. This route allows ready access to the superior vena cava for long-term central venous access, caustic or concentrated infusions, and central venous pressure monitoring. Pulmonary artery catheters and transvenous pacing wires can be introduced through the right internal jugular vein. The internal jugular vein is accessible without terminating cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) efforts, although chest compressions and the lack of carotid pulsations make accessing it difficult. The risk of a pneumothorax is probably less with the internal jugular vein cannulation as opposed to the subclavian vein route, although patient mobility is less and discomfort is greater. In a coagulopathic patient, the internal jugular vein puncture site is compressible, but hematoma formation may lead to compromise of the airway.

The subclavian vein is the preferred route for longer-term central venous access. This site allows for ambulation (unlike a femoral line) and neck movement without discomfort (unlike a jugular line). The catheter is concealable under clothing, making outpatient use more acceptable.

The femoral vein is often the preferred route for emergency central venous cannulation in many patients. The femoral vein is not a suitable route for ambulatory patients beyond the initial resuscitation and stabilization period. Femoral venous access is relatively easy during CPR and often does not require the cessation of chest compressions. The femoral vein is easily compressible. This makes it preferable to the subclavian vein in coagulopathic patients or those undergoing thrombolysis, although peripheral access would be preferred in these cases. A femoral vein central line should be changed as soon as possible to another site because of the increased rates of infection compared to other locations.

Internal Jugular Vein

Central Approach

Place the patient in the Trendelenburg position with their head down 15 to 30 degrees. Rotate the patient’s head away from the side that will be cannulated. Excessive rotation will distort the anatomic landmarks and may bring the internal jugular vein closer to the carotid artery.

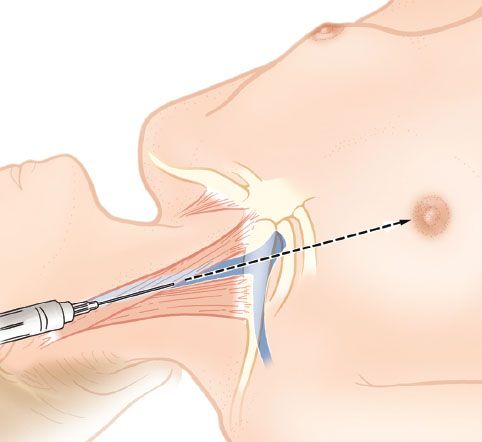

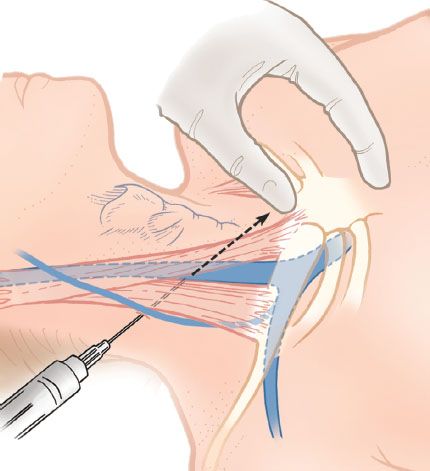

Insert the needle at a 30- to 60-degree angle at the apex of the triangle formed by the sternal and clavicular heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the clavicle (Fig. 5.3). Direct the needle toward the ipsilateral nipple. Shallower angles cause a greater amount of subcutaneous tissues and structures to be traversed before entering the vessel but are generally necessary in children whose vessels are smaller. Steeper angles make insertion of the catheter over the guidewire difficult as the guidewire tends to kink.

FIGURE 5.3 Central approach to the right internal jugular vein. (Reprinted with permission from Reichman EF. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.)

Anterior Approach

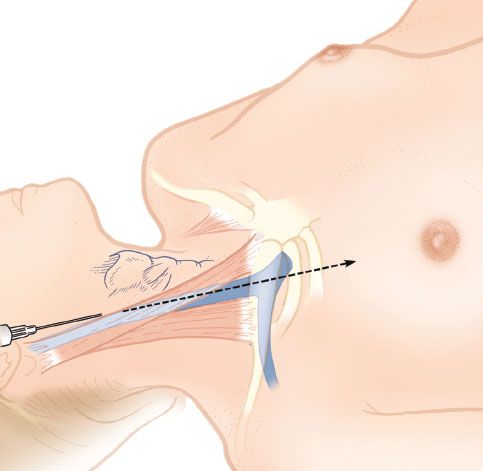

The skin puncture site is at the anterior border of the sternal head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, just lateral to the carotid artery (Fig. 5.4). Enter the skin at a 45- to 60-degree angle. Direct the needle toward the ipsilateral nipple. The internal jugular vein should be encountered within 3 to 5 cm in an adult. If the vein is not encountered by 5 cm, withdraw the tip of the needle to the subcutaneous space, and redirect it slightly medially.

FIGURE 5.4 Anterior approach to the right internal jugular vein. (Reprinted with permission from Reichman EF. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.)

Posterior Approach

Enter the skin at the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, one-third of the way from the clavicle to the mastoid process (Fig. 5.5). Alternatively, the point where the external jugular vein crosses the lateral border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle can be used. Direct the needle under the muscle at a 30- to 45-degree angle to the skin toward the sternal notch. Place the index finger of the nondominant hand in the sternal notch to provide a landmark with the patient draped. The internal jugular vein should be encountered within 5 cm in an adult. This approach is not recommended in children.

FIGURE 5.5 Posterior approach to the right internal jugular vein. (Reprinted with permission from Reichman EF. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.)

Subclavian Vein

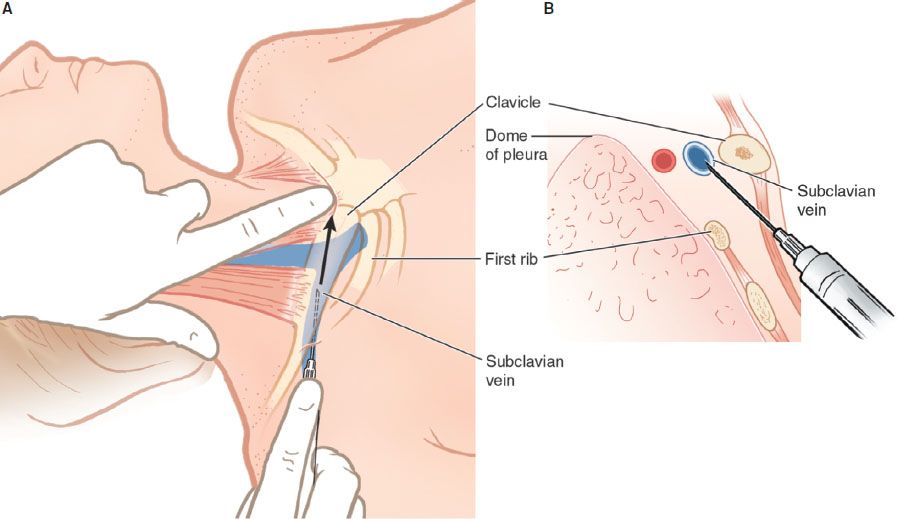

Infraclavicular Approach

The infraclavicular approach to the subclavian vein is most commonly used. This technique is easier to perform and less likely to result in a pneumothorax than the supraclavicular approach. Several different skin entry sites have been described (4). Some clinicians feel that the preferred entry site is 1 cm caudal to the junction of the medial third and middle third of the clavicle. The subclavian vein lies just posterior to the clavicle at this site. Direct the needle just superior and posterior to the suprasternal notch while staying as close to the frontal (coronal) plane as possible. The needle and syringe should be parallel to the bed (Fig. 5.6A,B). Placing the nondominant index finger in the sternal notch will help to guide placement (Fig. 5.6A).

FIGURE 5.6 Infraclavicular approach to subclavian vein cannulation. (Reprinted with permission from Reichman EF. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.)