INTRODUCTION

In contrast to the dramatic symptoms associated with acute valvular dysfunction, most valvular heart disease encountered in the ED is chronic and incidentally noted on exam. Adaptive responses preserve cardiac function and can delay the diagnosis of chronic valvular disease for decades but contribute to eventual cardiac dysfunction. Compared with the general population, patients with clinically evident valvular heart disease have a 2.5-fold higher death rate and a 3-fold increased rate of stroke.1

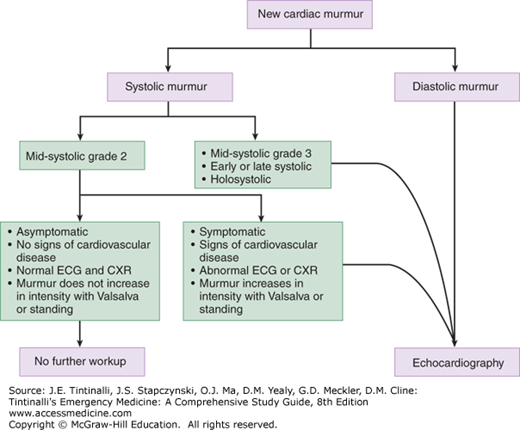

After discovering a new murmur, the first step in the ED is to determine the clinical significance. Benign or physiologic murmurs do not cause symptoms or findings compatible with cardiovascular disease; they are generally soft systolic ejection murmurs that begin after S1, end before S2, and are not associated with abnormal heart sounds. Systolic murmurs may be associated with anemia, sepsis, volume overload, or other conditions causing an increased cardiac output. Evaluation and treatment are focused on the underlying trigger rather than the murmur itself. Patients without chest pain, dyspnea, fever, or other signs attributable to valvular disease do not need emergent echocardiography but should be referred for eventual imaging.

Any diastolic murmur or new systolic murmur with symptoms at rest is pathologic and warrants emergent echocardiographic imaging. Patients with syncope from suspected aortic stenosis require admission for monitoring and echocardiography (Figure 54-1). Table 54-1 presents a grading system for murmurs. Another consideration in the newly diagnosed murmur is the possibility of endocarditis, especially in suspected valvular insufficiency (see chapter 155, “Endocarditis”).

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Faint, may not be heard in all positions |

| 2 | Quiet, but heard immediately with stethoscope placement onto the chest wall |

| 3 | Moderately loud |

| 4 | Loud |

| 5 | Heard with stethoscope partly off the chest wall |

| 6 | Heard when stethoscope is entirely off the chest wall |

MITRAL STENOSIS

Mitral stenosis prevents normal diastolic filling of the left ventricle. Despite declining frequency, rheumatic heart disease remains the most common cause worldwide. Rheumatic carditis causes fusion of valvular commissures, matting of chordae tendineae, and eventual calcification and limited mobility of the valve. Valvular obstruction is slowly progressive, often with 20 to 40 years before onset of symptoms. Mitral valve obstruction causes left atrial pressure to rise, resulting in left atrial enlargement, pulmonary congestion, pulmonary hypertension, and frequently atrial fibrillation. In severe disease, pulmonary hypertension may lead to pulmonic and tricuspid valve incompetence, pulmonary edema, right-sided heart failure, and bronchial vein rupture.

Mitral annular calcification is a slowly progressive nonrheumatic cause of mitral stenosis. It is more common among women, elderly, and those with hypertension or with chronic renal failure.2 Due to its slow progression, mitral annular calcification rarely causes severe symptoms.

Exertional dyspnea is the most frequent presenting complaint in patients with mitral stenosis. It is often precipitated by anemia or infection, which increases cardiac demand. Orthopnea and premature atrial contractions are also common. Symptoms associated with left- or right-sided heart failure may occur with more severe obstruction. Systemic emboli are a risk, especially when accompanied by atrial fibrillation. Due to earlier recognition and treatment, hemoptysis is a rare presenting symptom, although it can be massive.

Signs of mitral stenosis include a mid-diastolic rumbling murmur with crescendo toward S2. With the onset of atrial fibrillation, the presystolic accentuation of the murmur disappears. Typically, the S1 is loud and is followed by a loud opening snap that is high-pitched and best heard to the right of the apex (Table 54-2). The apical impulse is small and tapping due to an underfilled left ventricle. Systemic blood pressure is typically normal or low. If pulmonary hypertension is present, signs may include a thin body habitus, peripheral cyanosis, and cool extremities due to compromised cardiac output. Auscultatory findings are less obvious.

| Valve Disorder | Murmur | Heart Sounds and Signs |

|---|---|---|

| Mitral stenosis | Mid-diastolic rumble, crescendos into S2 | Loud snapping S1, small apical impulse, tapping due to underfilled ventricle |

| Mitral regurgitation | Acute: harsh apical systolic murmur starts with S1 and may end before S2 Chronic: high-pitched apical holosystolic murmur radiating into S2 | S3 and S4 may be heard |

| Mitral valve prolapse | Click may be followed by a late systolic murmur that crescendos into S2 | Mid-systolic click; S2 may be diminished by the late systolic murmur |

| Aortic stenosis | Harsh systolic ejection murmur | Paradoxical splitting of S2, S3, and S4 may be present; pulse of small amplitude with a slow rise and sustained peak |

| Aortic regurgitation | High-pitched blowing diastolic murmur immediately after S2 | S3 may be present; wide pulse pressure |

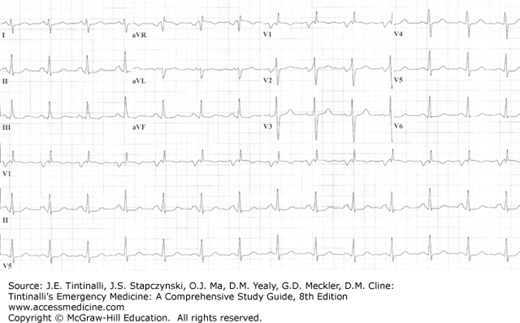

The ECG may demonstrate notched or biphasic P waves and right axis deviation in patients with mitral stenosis (Figure 54-2). On chest radiograph, straightening of the left heart border, indicating left atrial enlargement, is a typical and early radiographic finding. Eventually, findings of pulmonary congestion are noted.

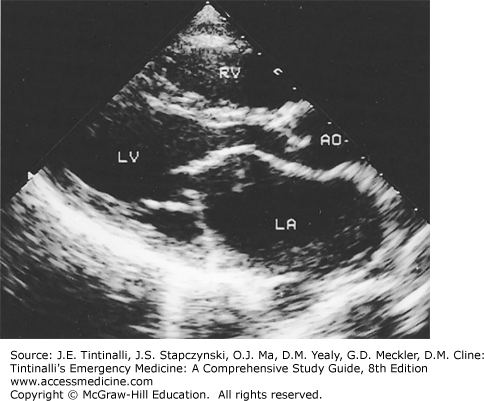

The diagnosis is confirmed with echocardiography (Figure 54-3). In candidates for surgical repair, transesophageal echocardiography best assesses the degree of mitral regurgitation and the presence of a left atrial thrombus.3

FIGURE 54-3.

Parasternal long-axis view of mitral stenosis. The left atrium is enlarged, mitral opening is limited, and doming of the anterior mitral leaflet is present. AO = aorta; LA = left atrium; LV = left ventricle; RV = right ventricle. [Reproduced with permission from Fuster V, O’Rourke RA, Walsh RA, Poole-Wilson P (eds): Hurst’s the Heart, 12th ed. © 2008, McGraw-Hill, New York.]

Medical management focuses primarily on symptom control and anticoagulation. Patients in atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response or with dyspnea on exertion may benefit from heart rate control (see chapter 18, “Cardiac Rhythm Disturbances”). Experts recommend anticoagulation if the left atrial diameter is greater than 55 mm or the patient has atrial fibrillation, a left atrial thrombus, or history of systemic emboli. In patients who present with hemoptysis from mitral stenosis–induced pulmonary hypertension, bleeding may be severe enough to require blood transfusion, emergent bronchoscopy, and consultation with a thoracic surgeon.

The most important ED action for patients with suspected but asymptomatic mitral stenosis is recognition and referral. The primary treatment for symptomatic disease is mechanical intervention, by balloon valvotomy, valve repair, or valve replacement, all optimally performed before the onset of severe pulmonary hypertension.

MITRAL REGURGITATION

Mitral regurgitation occurs when a dysfunctional valve allows retrograde blood flow from the left ventricle into the left atrium during systole. Most patients with mitral regurgitation follow a chronic and slowly progressive course. The most common cause is fibroelastic deficiency syndrome, seen primarily in the elderly.4 Mitral valve prolapse is another cause of mitral regurgitation and is typically found in younger patients. Secondary mitral regurgitation occurs when a dilated left ventricle causes papillary muscle displacement and valve dysfunction.

In chronic mitral regurgitation, the left atrium dilates to accommodate increasing regurgitant flow to keep left atrial pressure near normal. Stroke volume is augmented, maintaining effective forward flow despite a large regurgitant volume. In contrast, acute mitral regurgitation results in new-onset pulmonary vascular congestion and peripheral edema. Cardiogenic shock may also exist from impaired forward blood flow. Acute mitral regurgitation is typically caused by papillary muscle or chordae tendineae rupture from myocardial infarction or valve leaflet perforation from infective endocarditis. Blunt thoracic trauma and spontaneous chordae tendineae rupture are other rare causes.

Symptoms of acute mitral regurgitation are severe dyspnea, tachycardia, and pulmonary edema. Cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest can develop rapidly. Typical signs include an S4 gallop and a harsh apical systolic murmur loudest in early or mid-systole, diminishing before S2 (Table 54-2). Even with severe symptoms, the murmur may not be audible over breath sounds in the noisy ED environment. A hyperactive apical impulse may be apparent. In the setting of ischemia, chest pain may be masked by overwhelming dyspnea.

Chronic mitral regurgitation can be tolerated for years without symptoms. Eventually exertional dyspnea develops, sometimes associated with palpitations or atrial fibrillation. Signs include a late systolic left parasternal lift and lateral displacement of the apical impulse. A high-pitched holosystolic murmur is best heard in the fifth intercostal space and mid-left thorax and radiates to the axilla. The first heart sound is soft and often obscured by the murmur. An S3 is usually heard and is followed by a short diastolic rumble, indicating increased flow into the left ventricle. Given its slowly progressive course, signs of systemic thromboembolism may be the first suggestion of mitral regurgitation associated with atrial fibrillation.

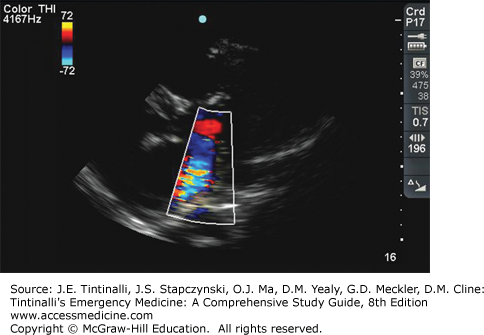

Think of acute mitral regurgitation in any patient with new-onset and marked pulmonary edema, especially in patients with near-normal heart size on chest radiograph or in those who do not respond to conventional therapy. Obtain an ECG to look for signs of ischemia, frequently in the inferior or anterior walls. In chronic mitral regurgitation, the ECG may demonstrate left atrial enlargement and left ventricular hypertrophy, and the chest x-ray shows left atrial and ventricular enlargement that is proportional to the severity of the regurgitant volume. Transthoracic echocardiography (Figure 54-4) diagnoses mitral regurgitation, but may underestimate the severity of regurgitation. If transthoracic echocardiography is nondiagnostic, cardiac MRI or transesophageal echocardiography may be undertaken.3 Exercise stress echocardiography may also be useful.

For acute mitral regurgitation due to papillary muscle rupture, emergency surgery is the treatment of choice. In the ED, start therapy with oxygen and positive-pressure ventilation for respiratory failure (see chapter 53, “Acute Heart Failure”). Nitrates provide afterload reduction, which results in increased forward flow into the aorta and partially restores mitral valve competence as left ventricular size diminishes. Inotropic therapy with dobutamine may be necessary. Aortic balloon counterpulsation increases forward flow and mean arterial pressure while diminishing regurgitant volume and left ventricular filling pressure.

Treatment of severe mitral regurgitation from acute myocardial infarction includes emergent revascularization.5 Endocarditis as a cause of acute mitral valve insufficiency requires specific evaluation and treatment (see chapter 155, “Endocarditis”).

Medical therapy may improve regurgitant flow and allow a delay to surgery. The key is emergency cardiology and surgical consultation while medically optimizing care.

In patients with chronic mitral regurgitation, treat acute symptoms. Control atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response with β-blockers or calcium channel blockers, and start anticoagulation to avoid embolization. Long-term management is best decided by the primary care provider or a cardiologist.

MITRAL VALVE PROLAPSE

Mitral valve prolapse is a systolic billowing of one or both leaflets into the left atrium occurring with or without mitral regurgitation. It is characterized by myxomatous degeneration of the valve caused by heritable defects in connective tissue proteins. It is the most common valvular heart disease in industrialized countries, affecting approximately 2.4% of the population.6 Morbidity and mortality are greatly influenced by the presence of concomitant mitral regurgitation.7

Most patients with mitral valve prolapse are asymptomatic. Associated symptoms can include nonclassic chest pain, palpitations, fatigue, anxiety, and dyspnea unrelated to exertion. Signs such as scoliosis, pectus excavatum, and low body weight can also be associated. If exercise induces symptoms, morbidity increases.8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree