VAGINAL BLEEDING

LAUREN E. ZINNS, MD, FAAP, JENNIFER H. CHUANG, MD, MS, JILL C. POSNER, MD, MSCE, MSEd, AND JAN PARADISE, MD

Vaginal bleeding is either a normal event or a sign of disease. Pathologic vaginal bleeding can indicate a local genital tract disorder, systemic endocrinologic or hematologic disease, or a complication of pregnancy. During childhood, vaginal bleeding is abnormal after the first few weeks of life until menarche. After menarche, abnormal vaginal bleeding must be differentiated from menstruation.

When evaluating patients with vaginal bleeding, it is important to distinguish between three types of bleeding: (1) Prepubertal bleeding, (2) bleeding in nonpregnant adolescent females, and (3) bleeding associated with pregnancy.

PREMENARCHAL VAGINAL BLEEDING

Evaluation and Decision

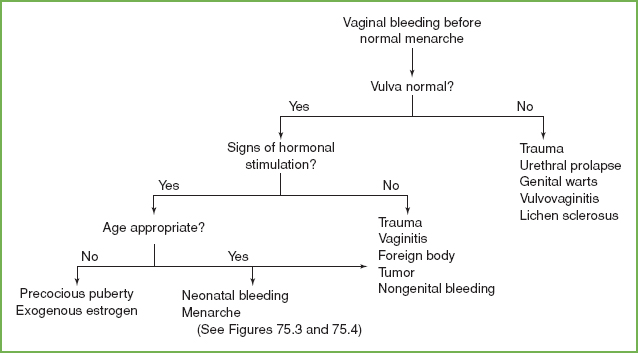

Important elements of the history include symptom onset, prior history of bleeding, associated abdominal pain, concern for foreign body, recent infections such as sore throat or diarrhea, rashes, masses, perineal skin changes, urinary and/or bowel symptoms and estrogen containing medications. When trauma is suspected, questions pertaining to the mechanism of injury and concerns for sexual abuse guide management (Fig. 75.1).

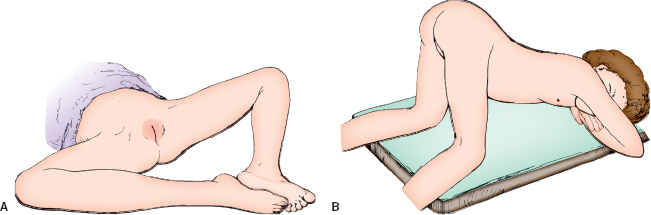

During the physical examination, the emergency clinician should note signs of hormonal stimulation (i.e., breast development, pubic hair growth, a dull pink vaginal mucosa, or physiologic leukorrhea), thyroid enlargement and skin findings such as petechiae, excessive bruising, or café-au-lait spots. Next, it is important to determine the source of bleeding. For the initial examination of the genitalia, an infant or child should be placed in frog-leg position with heels near the buttocks and while holding the legs flexed on the parent’s lap or examining table (Fig. 75.2A). After inspecting the external genitalia, the physician gently grabs the middle of both labia majora and applies outward, downward traction to visualize the introitus and identify the source of bleeding. If the vaginal tissues cannot be visualized adequately, the knee-chest position is an alternative examination technique, which allows for relaxation of the abdominal musculature is an alternative examination technique (Fig. 75.2B). A vaginal speculum should never be used in a young, awake child.

As genital injuries can be associated with peritonitis and/or rectal perforation, a careful abdominal examination and consideration for rectal examination is warranted. Occasionally, a need for a more thorough examination under anesthesia by a pediatric surgeon, urologist or gynecologist is necessary.

Laboratory evaluation for prepubertal patients is based upon the most likely diagnoses.

Vulvar Bleeding

The vulva consists of several structures: the labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, and vaginal introitus. A premenarcheal girl with the complaint of vaginal bleeding whose vulva looks abnormal may have a vaginal disorder, vulvar disorder, or both.

Trauma

Most vaginal trauma results from a blunt straddle injury from a fall onto a hard surface causing abrasion, laceration, or a hematoma of the anterior genital tissues (labia, urethra, or clitoris). Penetrating trauma and sexual assault may damage the posterior tissues as well (hymen, vagina, rectum). Even a minor vulvar injury should alert the emergency physician to the possibility of concurrent, potentially serious vaginal, rectal, or abdominal injuries.

Vulvar lacerations do not often bleed excessively and usually do not require repair. However, resulting hematomas can extend widely through the tissue planes, forming large, painful masses that occasionally produce enough pressure to cause necrosis of the overlying vulvar skin. Pressure dressings and ice packs can aid with healing. Since minor periurethral injuries can produce urethral spasm and acute urinary retention, the injured child’s ability to void should be assessed. Consider the possibility of sexual assault in every child with a genital injury.

Genital Warts

Similar to vulvar trauma, genital warts are recognized by inspection and can produce bleeding from minor trauma when they are located on the mucosal surface of the introitus. They appear as flesh-colored papules and are usually due to the human papilloma virus (HPV). In children younger than 2 years old, maternal-child transmission during vaginal birth is the most likely source. However, careful evaluation for sexual abuse in children >2 years old is indicated including screening for concurrent sexually transmitted infections and reporting to the State Child Protective Services Agency (see Chapter 95 Child Abuse/Assault). Topical podophyllin, used to treat warts, can produce systemic toxicity if absorbed in large amounts. A dermatologist or other knowledgeable clinician should be consulted to select an appropriate treatment for bleeding genital warts.

Vulvovaginitis

Vulvar inflammation can be seen in patients with bacterial or fungal vulvovaginitis (see also Chapter 76 Vaginal Discharge). Infections caused by Shigella species, group A hemolytic streptococci, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Candida albicans produce vaginal bleeding or bloody discharge in a number of cases. Cultures to guide therapy can be collected by inserting a cotton swab in the vagina; avoid contact with the hymenal tissues to reduce pain. Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm) infestations, though typically rectal, may also involve the vagina. Vigorous scratching may cause excoriation and resultant bleeding in the perineal area. Emergency physicians should recommend sitz baths, avoidance of bubble baths, thorough drying after bathing, and front-to-back wiping in all patients with vulvovaginitis. Occasionally, antibiotics or anthelmintics may be necessary depending on the organism isolated.

FIGURE 75.1 Diagnostic approach to vaginal bleeding before normal menarche.

Lichen Sclerosis

Although bleeding per se is not common, ecchymoses, fissures, and telangiectasias are frequent clinical manifestations of lichen sclerosis, an uncommon, chronic, idiopathic skin disorder in children that most often affects the vulva. In this hyperestrogenic condition, white, flat-topped papules gradually coalesce to form atrophic plaques that involve the vulvar and perianal skin in a symmetric hourglass pattern. Topical treatment with corticosteroids or an immunomodulator is helpful in most cases. Consultation with a specialist is suggested for management of this uncommon disorder.

VAGINAL BLEEDING

Bleeding in the Neonate

During the first 2 weeks of life, hormonal fluctuations produce physiologic endometrial bleeding. Before female infants are born, high levels of placental estrogen from the mother stimulate growth of both the uterine endometrium and the breast tissue. As this hormonal support decreases after birth, some infants have an endometrial slough that results in a few days of light vaginal bleeding. The bleeding will stop spontaneously and requires no treatment except parental reassurance. A further workup is necessary if the bleeding persists after 3 weeks.

Bleeding in Young Children

Precocious Puberty

Precocious puberty is characterized by cyclic bleeding with or without associated breast development (thelarche), pubic hair growth (adrenarche), or accelerated linear growth in girls less than 8 years of age. Always consider possible exposure to exogenous feminizing hormones (e.g., creams or medications containing estrogen). Other considerations include ultrasound to identify an abdominal mass (endocrinologically active ovarian tumor or cyst affecting the gonads) and a careful examination to evaluate for central nervous system mass, symptoms/signs of hypothyroidism blood or coagulation disorders, or the presence of unilateral café-au-lait spots that may suggest McCune–Albright syndrome. The evaluation for precocious puberty is rarely emergent and best referred to a pediatrician and/or pediatric endocrinologist.

FIGURE 75.2 A: Girl in the frog-leg position for the examination of the external genitalia. B: Girl in the knee-chest position with exaggerated lordosis and relaxed abdominal muscles. The examiner can inspect the interior of her vagina by gently separating her buttocks and labia, using an otoscope without an attached speculum for illumination.

Foreign Body

Although a chronic, foul-smelling discharge is often considered the hallmark of a vaginal foreign body, many girls have intermittent vaginal bleeding or scant vaginal discharge. Direct inspection of the vaginal vault using the frog-leg or knee-chest position (Fig. 75.2B) usually reveals the foreign body easily. While the most common foreign body—toilet paper—is not radiopaque, pelvic ultrasound may be useful when toy parts, crayons, or coins are suspected. If a foreign body is strongly suspected but cannot be seen, vaginal irrigation often successfully flushes out the foreign body. Instill normal saline via gravity using a Foley catheter and a 50-mL syringe with the plunger discarded. Application of 2% viscous lidocaine to the introital tissues reduces discomfort and the majority of children tolerate the procedure well. A rectal examination may provide further information. An examination under procedural sedation or general anesthesia with a pediatric gynecologic specialist is sometimes necessary to ensure that a retained foreign body is removed to prevent complications such as fistula formation and vaginal stenosis.

Infections

About half of all patients with Shigella vaginitis have bleeding that may be more noticeable than vaginal discharge. Most patients do not have concurrent diarrhea. Vaginal infections with group A streptococci, N. gonorrhoeae, and C. albicans also cause bleeding in some cases. A vaginal culture will provide the diagnosis and guide the selection of appropriate therapy. The manifestations and treatment of vaginal infections in children are discussed in more detail in Chapters 76 Vaginal Discharge and 100 Gynecology Emergencies.

Tumors

Malignant tumors, such as endodermal sinus tumors and rhabdomyosarcomas including sarcoma botryoides are a rare cause of vaginal bleeding in young females. Sarcoma botryoides present as a polypoid, “grape-like” mass protruding from the introitus and often has metastasized to the lungs, pericardium, liver, kidney, and bones when initially diagnosed. Peak incidence is 2 years of age but can present between 1 and 5 years old. Pelvic ultrasound aids in making this diagnosis. A pediatric gynecologist and oncologist should be consulted immediately because treatment requires surgical excision, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy after a tissue biopsy.

Vascular Anomalies

Vascular anomalies, such as malformations or tumors, may cause vaginal bleeding in young children. Infantile hemangiomas are the most common vascular tumor, occurring in up to 10% of white, non-Hispanic females. They are often associated with prematurity and infants of mothers with multiple gestation, advanced maternal age, placenta previa, or preeclampsia. They typically present in the first weeks of life and tend to regress spontaneously. Infrequently, they may lead to ulceration and bleeding. Treatment with corticosteroids, laser therapy, and possible excision may be necessary.

Idiopathic

Occasionally, a prepubertal patient with a history of vaginal bleeding has no abnormalities and no bleeding at the time of the examination. The patient’s urine and stool should be checked for blood and close follow-up with the pediatrician or a gynecologic specialist may be warranted.

Urethral Bleeding

Urethral prolapse (see Chapter 100 Gynecology Emergencies) is a common cause of apparent vaginal bleeding. Urethral prolapse more commonly affects school-aged African-American children. The etiology remains unknown. Factors contributing to urethral prolapse include estrogen deficiency, trauma, urinary tract infection, weak pelvic floor muscles, and increased intra-abdominal pressure associated with chronic cough or constipation. Some patients with urethral prolapse complain of dysuria or urinary frequency but most have painless bleeding as their only symptom. Prolapse is diagnosed by its characteristic nontender, soft, doughnut-shaped mass anterior to the vaginal introitus. The ring of protruding urethral mucosa is swollen and dark red with a central dimple that indicates the meatus. When the child is supine, the prolapse is often large enough to cover the vaginal introitus and appears to protrude from the vagina. Bleeding comes from the ischemic mucosa. Urethral prolapse is sometimes mistaken for a urethral cyst or polyp, which may lead to vaginal bleeding; these lesions do not surround the entire urethral orifice symmetrically. If the diagnosis of urethral prolapse is in doubt, one may safely catheterize the bladder through the prolapse to obtain urine. Most patients will improve with the use of sitz baths and topical estrogen creams applied twice daily. In rare circumstances where the patient has difficulty voiding or if estrogen therapy fails, referral for surgical evaluation and possible excision of the prolapsed tissue is necessary.

ABNORMAL BLEEDING AFTER MENARCHE

When an adolescent girl presents with a chief complaint of irregular menses, the ED physicians must first differentiate between normal and abnormal bleeding. In most cases, a comprehensive history and physical examination, along with minimal ancillary testing, will uncover the etiology and guide management. An understanding of the menstrual cycle and its hormones is key to treating the most common cause of adolescent uterine bleeding, anovulatory cycles.

Normal Menstrual Cycle

Menstrual patterns during the first 2 years after menarche vary. The normal menstrual cycle averages 28 days but varies from 21 to 35 days. Ninety-five percent of young adolescents’ menstrual periods last between 2 and 8 days; duration of 8 days or more is abnormal. An occasional interval of less than 21 days from the first day of one menstrual period to the first day of the next is normal for teenagers, but several short cycles in a row are abnormal. Typical bleeding requires adolescents to change a pad or tampon 4 to 5 times daily without resultant anemia.

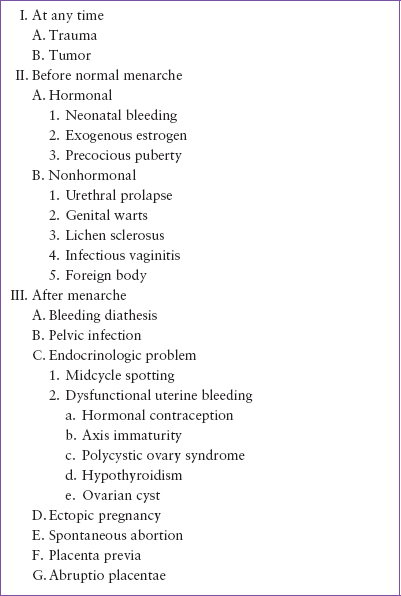

TABLE 75.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF VAGINAL BLEEDING

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree