Chapter 27 Using Human Factors to Balance Your Operating Room

Health care is an inherently risky business, and with that risk errors are inevitable. Medical errors represent a public health issue that has been increasingly well recognized since the sentinel Institute of Medicine report (Kohn et al, 2000) was published a decade ago. Since then, the demands on health care to redesign processes to ensure a safer system have been increasing. Despite the efforts of health care leaders, policy makers, and public health advocates, however, the number of errors continues to rise (HealthGrades Inc., 2006). As one of the most complex work environments in health care (Christian et al, 2006), the operating room (OR) is a common site for adverse events (Leape, 1994). It involves teams of highly trained professionals interacting with advanced technology in high-risk situations, and the nature of such work places these teams at risk for errors. The largest numbers of errors result from treatment provided in the OR (Gawande et al, 2003; Brennan et al, 2004). The causes of these errors are variable and include technical errors (Gawande et al, 2003; Rogers et al, 2006) and communication deficiencies (Sexton et al, 2000; Christian et al, 2006; Rogers et al, 2006).

THE OPERATING ROOM AS A MICROSYSTEM

Viewing the OR as a microsystem provides a basis for understanding the complexity of systems, and this shifting of approach may allow for a significant decrease in errors (Weigmann et al, 2007). From the systems perspective, errors are viewed as a consequence of a system breakdown rather than being caused by an individual working in the system. This thinking is fundamental to the field of human factors, which has been used in other complex industries to balance the components of work (Yourstone and Smith, 2002).

HUMAN FACTORS

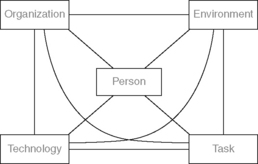

In their study of work systems, Smith and Sainfort (1989) developed the Balance Theory to conceptualize the interaction of five human factors components within the system: the individual, tasks, tools and technologies, the environment, and organizational factors (Figure 27-1). These components work together to create a “stress load” that challenges an individual’s biological, psychologic, and behavioral resources (Carayon and Smith, 2000). These five components should be considered equally when designing a product, process, or system to achieve effective, efficient, and safe results. This chapter presents those human factor components as they relate to the OR and discusses how balancing all five factors within a work system can improve patient safety.

BALANCE THEORY

Individual

The characteristics of an individual in the work system include everything the perioperative nurse “brings” to work, including individual characteristics such as past experience, abilities, physical and emotional health, motivation, and professional aspirations. Many of these characteristics are not static. Fatigue, for example, has been implicated in errors in disasters such as the Exxon Valdez oil spill, Chernobyl nuclear disaster, and Three Mile Island situation (Mitler et al, 1988). Adverse surgical outcomes have been linked to fatigue (Gaba and Howard, 2002), and, although little is known specifically about the impact of fatigue on the practice of OR nursing, it presents some unique challenges.

Fatigue

In addition to working a full-time schedule, perioperative nurses often need to take call. Balancing work and personal obligations becomes more difficult, which can force nurses to work without adequate sleep. Lack of sleep impairs one’s ability to deliver safe care. Research has shown that after 17 hours without sleep, performance is equivalent to having a blood alcohol level of 0.05% (Page et al, 2009); it further degrades to 0.10% after 24 hours without sleep (Rosekind et al, 1997). Recognizing fatigue as an important factor in the OR, the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) has issued a position statement based on an extensive review of the literature outlining recommendations for safe on-call practices (AOR, 2008).

Experience Level

• Humans have a limited short-term memory capacity, so use checklists to reduce reliance on memory.

• Sensory overload in the OR requires staff to be constantly alert to everything around them. Limiting the availability of choices, such as by using unit dose medication whenever possible, can decrease the likelihood of a medication error.

• Cognitive tunnel vision can occur related to stress in high-intensity situations. Using forcing functions whenever possible, such as automatic shut-off valves on warming devices, can mitigate this risk.

Task

According to the Balance Theory, the tasks of the work system affect and are impacted by the individual, technology, and the environment (Carayon and Smith, 2000). The tasks required in the OR must be considered to achieve a balanced work system, necessitating attention to concepts such as the appropriate use of skills, workload, and work pressures.

The ability to identify and prioritize the enormous number of individual tasks required of a perioperative nurse is a skill that evolves along the novice-to-expert continuum. Time pressures, combined with high-level multitasking, are routine. Nurses face significant competition for attention during routine and critical points in a surgical procedure (Christian et al, 2006). The workload in the OR varies and is affected by the need to retrieve additional resources, such as supplies and equipment, and the need to perform safety-related activities, such as “count” and handoff. The requirements of these tasks are physical and cognitive. Standardization and simplification should be the mantra for developing error reduction strategies for the task component of a balanced work system. As part of the “Safe Surgery Saves Lives” campaign, the World Health Organization (WHO) (2008) developed the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist, which can be used to remind the surgical team of key tasks to be performed in the preoperative, intraoperative, and immediate postoperative phases of care (World Alliance for Patient Safety, 2008).

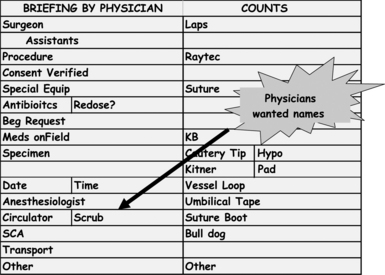

Situational awareness, a concept borrowed from high-reliability organizations (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2001), allows members of the team to have an accurate understanding of “what’s going on” and “what is likely to happen next.” It allows the entire team to be on the same page. Institutions across the country are identifying ways to increase situational awareness in their ORs. Memorial Health System in Colorado Springs, Colorado, identified briefings as the first step in creating situational awareness. The elements of briefing were determined by the Unit Practice Council and were designed into the current “count board,” which offers the appropriate visual cue when in the OR scrubbed and standing at the table (Figure 27-2). Electronic documentation of a physician-led briefing was later added to facilitate the collection of metrics for this process improvement (Figure 27-3). Likewise, during the design and construction of their OR platform, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York developed the concept of the “wall of knowledge” (Figure 27-4). One component of the wall of knowledge is the “OR dashboard,” which displays continuous real-time data to all members of the surgical team regarding patient information, the progress of the case, and team members.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree