Chapter 11 To Count or Not to Count

A Surgical Misadventure

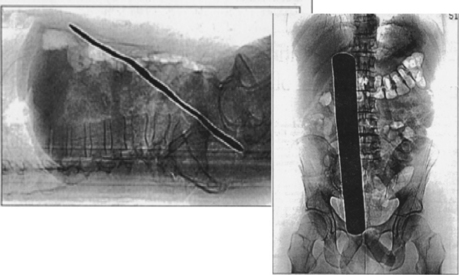

On August 1, 2007, in the Inpatient Prospective Payment System Fiscal Year 2008 Final Rule, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2008) identified eight hospital-acquired conditions that are (1) high cost or high volume or both, (2) result in the assignment of a case to a diagnosis-related group that has a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis, and (3) could reasonably have been prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines. The first item on that list is a foreign object retained after surgery. For discharges occurring on or after October 1, 2008, hospitals will not receive additional payment for cases in which one of the selected conditions was not present on admission. That is, the case will be paid as though the secondary diagnosis were not present. An unintended retained foreign body (RFB) has become one of the never events in an age in which both quality and efficiency are paramount and becoming more and more linked to pay for performance (Thomas and Caldis, 2007). This then begs the question as to whether or not the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses’ (AORN’s) “Recommended Practices for Sponge, Sharps, and Instrument Counts” can be considered an evidence-based guideline. Would the routine counting of surgical instruments have prevented leaving behind a 2- by 13-inch malleable retractor? How does one explain that error to the patient, the family, and the public when something this large and obvious is left behind (Figure 11-1)?

Figure 11-1 Retained malleable rectractor, 2001.

(From King CA: To count or not to count: a surgical misadventure. Perioperative Nurs Clin 3(4):395–400, 2008.)

NORMALIZATION OF DEVIANCE

What happened in this case that predisposed it to an RFB? Two major patient safety issues became apparent during an internal claims closed-case review. One was the normalization of deviance, whereby there was a drift from the norm to the point that the deviance became the norm (Groom, 2006; Marx, 2008). People cut corners and drifted from the norm (e.g., counting of instruments) because until then nothing bad had happened. It was not the policy, nor was there a procedure in place at this facility for the counting of instruments (Thomas and Caldis, 2007). There was a generalized perception that instruments had never been left in patients at this facility; therefore the counting of instruments was not necessary. James Reason writes, that “All errors involve some kind of deviation. In cases of slips, lapses, and fumbles, actions deviate from the current intention” (Reason, 2005).

RISK FACTORS

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating risk factors related to RFBs. Gawande et al (2003a), in an analysis of errors reported by surgeons at three teaching hospitals, found that one half to three quarters of adverse events are attributable to surgery and that more than 50% are preventable. The incidence of RFBs has been reported to be somewhere between 1 in 9000 and 1 in 19,000 surgical cases (i.e., 0.0001 to 0.00005), which may be translated to 1 or more a year within a large medical facility (Gawande et al, 2003b). Greenberg (2007) reported that a discrepancy may occur in about 1 out of 8 general surgery cases, with these discrepancies increasing the risk for an RFB. Given the risk and consequences related to RFBs and the fact that AORN’s “Recommended Practices” (2008) represent “… what is believed to be an optimal level of practice (i.e., care),” the perioperative nurse has a professional duty and an inherent ethical and legal obligation to prevent harm such as an RFB.

LEGAL STANDARD OF CARE

The law requires only that unintentional foreign bodies not be negligently left in patients. “The law does not prescribe how counts should be performed, who should perform them, or even that that they need to be performed” (AORN, 2008). It is the individual perioperative nurse’s professional responsibility to act as a prudent nurse would under the same or similar circumstances. It would behoove the prudent perioperative nurse to seek direction from AORN’s “Recommended Practices” (2008), which recommends that sponges, needles, instruments, and other items “… be counted on all procedures in which the possibility exists that [an item] could be retained.” The employer is responsible for the employee’s actions that are taken within the scope of his or her employment. Upon accepting employment, there is an implied agreement between the perioperative nurse and the employer that he or she will perform within the standard of care (i.e., standards of practice). The legal standard of care refers to what any prudent nurse with similar training, experience, or education would do in the same or similar situation. Failure to demonstrate this standard of care is considered negligence. The doctrine of res ipsa loquitur (the thing speaks for itself) applies to RFBs, rendering this sort of litigation almost indefensible (Aiken, 1998). In cases involving an RFB, the retained object presents as prima facie evidence of negligence. Before 1977 the surgeon may have been held ultimately responsible for an RFB under the captain-of-the-ship doctrine. However, in 1977 the Texas Supreme Court ruled in favor of the surgeon, Sparger v Worley Hospital, Inc., 547 SW2d 582 (Tex 1977), refusing to apply the captain-of-the-ship doctrine by finding that the incorrect sponge count was the responsibility of the nursing staff and therefore the hospital (Iyer, 2001). Such a breach in one’s duty to deliver the standard of care or the failure to act as a reasonable person would act in a similar situation falls into the category of an unintentional tort or negligence (Aiken, 1998). Although AORN is not a regulatory body and therefore AORN’s “Recommended Practices” are not enforceable under the law, an individual’s behavior is held up to that of the “Recommended Practices” because they are often cited as what a prudent nurse would do in the same or similar situation. Schroeter (2004) describes the perioperative nurse’s ethical obligation as it relates to practice standards by stating, “Nurses must be able to act to ensure that safe, competent, legal, and ethical care is provided to all patients.”

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Kaiser et al (1997) studied the frequency of occurrence of retained surgical sponges by examining RFB insurance claims over a 7-year period. Forty-eight percent (n = 40) of this sample involved retained surgical sponges. A falsely correct sponge count was documented in 76% of the abdominal cases in this study. In 1996 the costs were reported at $2,072,319 in total indemnity payments and $572,079 in defense costs. In 3 of the 40 cases the surgeon was found guilty of negligence by the court despite the nursing staffs’ admitted liability. In a retrospective study of 24 patients presenting with an RFB after abdominal surgery, Gonzalez-Ojeda et al (1999) reported that RFBs may occur at a rate of 1 in 1000 to 1500 open-abdominal procedures.

Risk Factors

Although there are upwards of 1300 published papers found when using the search term “retained foreign body, surgery” at the PubMed Web site, the first comprehensive study to identify risk factors for RFBs was undertaken between 1985 and 2001. It used a retrospective case-control methodology of reviewing the medical records associated with claims and incidence reports of RFBs. Gawande et al (2003b) concluded that the risk for an RFB significantly increases during emergency procedures, when there are unplanned changes in the procedure, and in patients with a significantly higher body mass index. In patients presenting with an RFB, it was less likely that a surgical count had been performed. Gawande et al recommended that using a counting process similar to AORN’s “Recommended Practices,” monitoring personnel’s compliance with the process, and using radiologic screening of patients at high risk for RFBs are measures that may be implemented to prevent an RFB. Based upon projections of Gawande et al, the ratio of the number of radiographs it would take to detect an RFB is about 300:1 and very dependent on the quality of the film and expertise of the person reading the film. Yet the cost-benefit ratio is about $50,000 paid out in claims versus about $100 for the cost to obtain a plain radiograph to detect an RFB. Given the risk-benefit ratio to the patient, performing a plain radiograph to detect or rule out an RFB would seem a far more prudent practice than to do nothing at all.

SENTINEL EVENT

What happened in the case depicted in Figure 11-1 that contributed to leaving behind a malleable retractor? The superseding causal effect was the normalization of deviance, a cultural-sociologic phenomenon whereby individuals or teams repeatedly accept lower standards of performance until the lower standard becomes the norm. There was a prevailing attitude of complacency about counting instruments because “nothing has happened so far.” We see this often in health care. Eventually the attitude that nothing has happened “yet” becomes the norm, and therein lies the danger (Groom, 2006). The facility in which this event occurred did not routinely count surgical instruments because “nothing has happened” and because the prevailing belief was that there were no data supporting the manual counting of instruments as a reliable method of prevention. “This again appears to substantiate the danger of not knowing what one does not know” (Rhodes, 2003). What was lacking was transparency and two-way communication between the risk management and claims departments and the management of the operating room (OR). What would become evident upon closer examination was that there was indeed a problem; the incidence of RFBs averaged about 1.8 per year at this facility.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree