INTRODUCTION

TESTICULAR TORSION

Young men (average age 16-17.5 years) complain of the sudden onset of pain in one testicle, followed by swelling of the affected testicle, reddening of the overlying scrotal skin, lower abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. An examination reveals a swollen, tender, retracted testicle that often lies in the horizontal plane (bell-clapper deformity). The spermatic cord is frequently swollen on the affected side. In delayed presentations, the entire hemiscrotum may be swollen, tender, and firm. The urine is usually clear with a normal urinalysis. In one-third of cases, there is a peripheral leukocytosis.

Obtain urologic consultation immediately and prepare to go to the operating room without delay. Doppler ultrasound or technetium scanning may be helpful if these procedures will not delay surgery. In the interim, detorsion may be attempted if the patient is seen within a few hours of onset: open the affected testicle like a book, that is, the right testicle turned counterclockwise when viewed from below and the left testicle turned clockwise. Pain relief is immediate. Decreased pain prompts additional turns (as many as three) to complete detorsion; increased pain prompts detorsion in the opposite direction. Do not delay operative intervention for ancillary studies since testicular infarction will occur within 6 to 12 hours after torsion.

The cremasteric reflex is almost always absent in testicular torsion.

Patients may report similar, less severe episodes that spontaneously resolved in the recent past.

Half of all torsions occur during sleep.

Abdominal or inguinal pain is sometimes present without pain to the scrotum.

The age of presentation has a bimodal pattern, since torsion is more prevalent during infancy and adolescence.

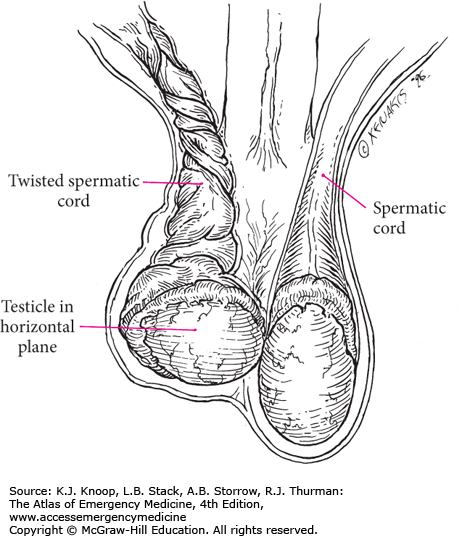

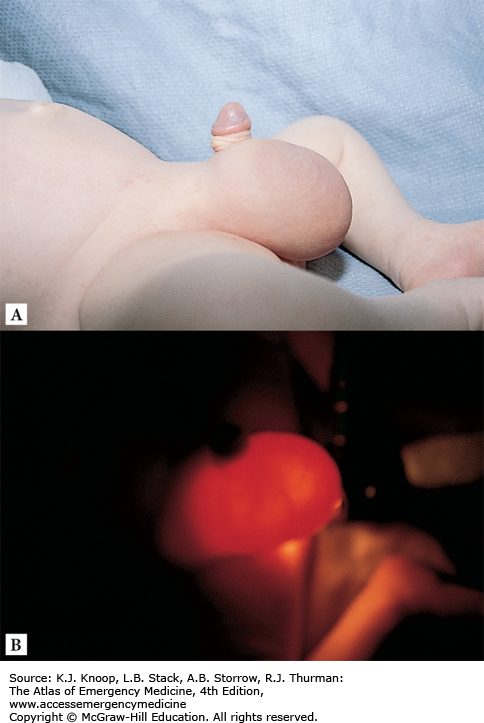

FIGURE 8.2

Bell-Clapper Deformity. Twisting of the spermatic cord causes the testicle to be elevated with a horizontal lie. Lack of fixation to the posterior scrotum predisposes the freely movable testicles to rotation and subsequent torsion. Asymptomatic patients with bell-clapper deformity are at risk for torsion.

TORSION OF A TESTICULAR OR EPIDIDYMAL APPENDIX

Vestigial remnants in the embryology of the scrotum are often found on the superior portions of the testicle or the epididymis. These appendages, which have no known function, are occasionally on a stalk that is subject to torsion. This most commonly occurs in boys up to 16 years of age but has been reported in adults. The patient complains of sudden pain around the superior pole of the testicle or epididymis as the appendix undergoes necrosis and inflammation. Early in the course, palpation of a firm, tender nodule in this area will confirm the diagnosis.

Obtain urologic consultation immediately. Differentiating from the more emergent testicular torsion is the key responsibility. Ancillary studies are generally not helpful in making this diagnosis unless it presents very early in its course. A urinalysis is generally normal. The characteristic physical signs of a small, tender, upper-pole nodule along with a color Doppler ultrasound showing good flow to the testicle may mitigate the need for emergent surgery. With later presentations or an equivocal ultrasound, the diagnosis may not be made with confidence before surgery. If surgery is not deemed necessary by the urologic consultant, analgesics and rest are all that is required. The appendix will involute and calcify in 1 to 2 weeks.

Stretching of the scrotal skin across the necrotic nodule will occasionally reveal a bluish discoloration of the nodule, called the “blue-dot sign.” This is pathognomonic for torsion of the appendix.

A reactive hydrocele may accompany appendiceal torsion. When the hydrocele is transilluminated, the blue-dot sign may be revealed.

ACUTE EPIDIDYMITIS

The onset of scrotal pain typically occurs over hours and is often referred to the ipsilateral inguinal canal or lower abdominal quadrant. Recent urinary tract instrumentation or urinary tract infection is a risk factor. Early in the course, a tender, indurated, edematous epididymis is palpated separately from the nontender testicle. Late presentations will have generalized scrotal swelling and tenderness, making examination and differentiation more difficult. The urinalysis reveals pyuria or bacteriuria half of the time and the peripheral white blood cell count is frequently elevated. Patients can present with fever and signs of sepsis.

Direct outpatient treatment of younger men (<35 years) at sexually transmitted organisms. Older men tend to have infections caused by organisms in common with urinary tract infection. Refer adolescents and children for urological evaluation to rule out congenital anomalies, which are common in nongonococcal infections in this age group. Consider admission and IV antibiotics for febrile patients.

Elevation of the affected hemiscrotum while supine may provide relief of symptoms (Prehn sign).

Evaluate older men for urinary retention, as this is a frequent cause of epididymitis.

Testicular tumors are most frequently misdiagnosed as epididymitis.

The absence of pyuria or bacteriuria does not exclude the diagnosis.

Referred pain to the lower quadrants can mimic appendicitis or diverticulitis.

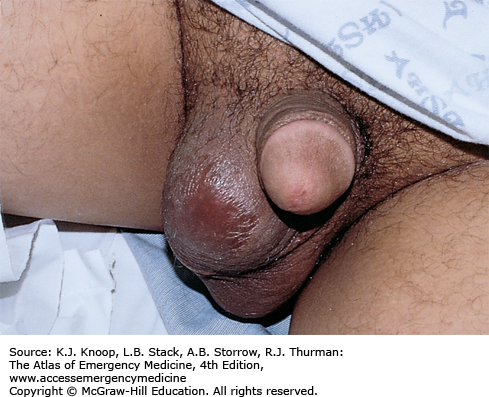

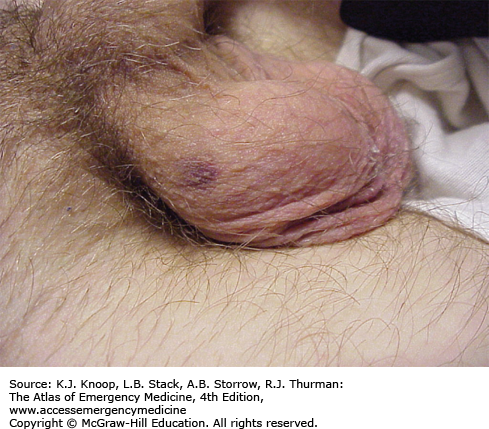

FIGURE 8.8

Acute Epididymitis. (A) Swelling of the right hemiscrotum and tenderness of the inferior posterior portion of the testicle. (Photo contributor: Emergency Medicine Department, Naval Medical Center Portsmouth.) (B) Diffuse and erythema swelling of the entire scrotum. (Photo contributor: Cyril Thomas, PAC.)

ORCHITIS

Orchitis has a variable onset and is mildly uncomfortable or severely painful. It is most frequently a complication of mumps infection and more rarely other viruses. Bacterial orchitis is rarer still and associated with concurrent epididymitis. Mumps orchitis occurs 4 to 7 days after parotid symptoms with testicular pain and swelling. It is unilateral 70% of the time with a contralateral infection developing later 30% of the time. The testicle is swollen and tender, sparing the epididymis. The overlying scrotal skin can be edematous and erythematous. Constitutional symptoms of malaise, headache, myalgias, and fever are common.

Supportive care with analgesics, hot or cold packs, and scrotal elevation is sufficient for mumps orchitis. Bacterial orchitis is treated the same as epididymitis.

Pain and swelling from mumps orchitis mimics testicular torsion mandating Doppler ultrasonography to differentiate.

An enlarged, tender epididymis or boggy, tender prostate supports bacterial orchitis.

Preceding or concurrent parotid swelling supports mumps orchitis.

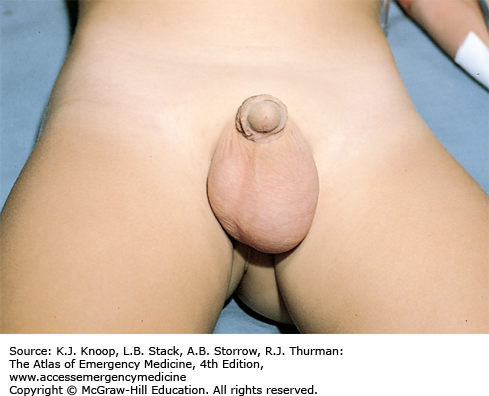

HYDROCELE

Most hydroceles occur in older patients and develop gradually without any significant symptoms. Hydrocele presents as a soft, pear-shaped, fluid-filled cystic mass anterior to the testicle and epididymis that will transilluminate. However, it can be tense and firm and will transilluminate poorly if the tunica vaginalis is thickened. Almost all hydroceles in children are communicating, resulting from the same mechanism that causes inguinal hernia. A persistent, narrow processus vaginalis acts like a one-way valve, thus permitting the accumulation of dependent peritoneal fluid in the scrotum. Acute symptomatic hydroceles are rarer and can occur in association with epididymitis, trauma, or tumor.

In an acute hydrocele, direct treatment at discovering a possible underlying cause. A positive urinalysis may point toward an infectious etiology. Transillumination helps demonstrate whether the mass is cystic or solid. Ultrasound can be very helpful in imaging the scrotal contents and delineating the composition of the mass. Acute hydroceles should not be considered benign and require referral to a urologist to rule out tumor or infection. Refer chronic accumulations to a urologist on a more routine basis for elective drainage.

Ten percent of testicular tumors have a reactive hydrocele as the presenting complaint.

An inguinal hernia with a loop of bowel in it may emit bowel sounds.

Hydroceles are almost never symptomatic.

Acute reactive hydroceles may be caused by infection, trauma, or torsion.

TESTICULAR TUMOR

In testicular tumor, a painless, firm testicular mass is palpated, with the patient often complaining of a “heaviness” of his testicle. If the patient presents early, the mass will be distinct from the testis, whereas later presentations will have generalized testicular or scrotal swelling. These lesions occasionally present with pain due to infarction of the tumor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree