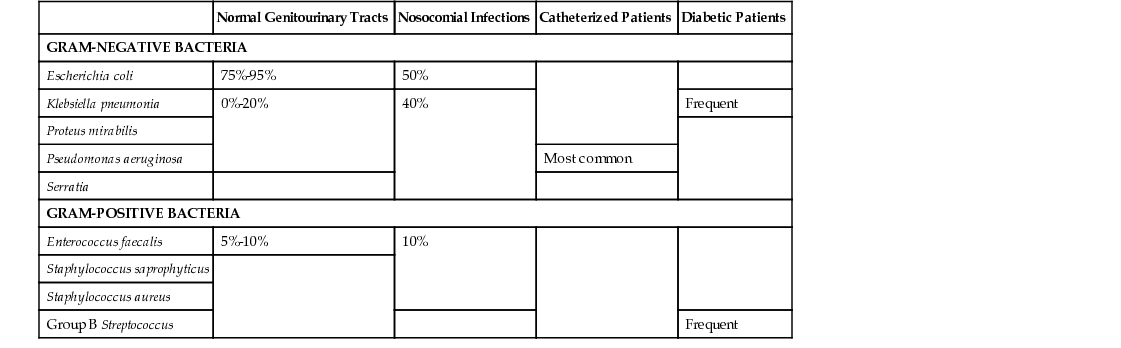

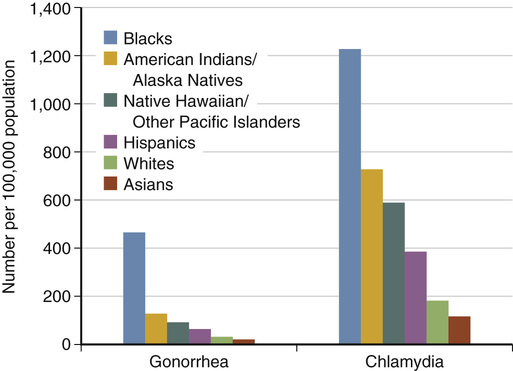

Joann D. Lepke Urinary tract infection (UTI) is a broad term used to describe acute or chronic infection and/or inflammation of the bladder (cystitis), urethra, prostate, ureter, or kidney (pyelonephritis) with microbial colonization of the urine.1 UTIs have six categories of classification: uncomplicated, complicated, isolated, unresolved, reinfection, and relapse.2 UTIs are considered complicated if they include the presence of pyuria, positive urine culture, fever, or structural or functional abnormality of the urinary tract or if they occur in the presence of urinary catheterization. All UTIs in males are considered complicated.3 Uncomplicated UTIs include those typically occurring in otherwise healthy, immunocompetent, nonpregnant women with no significant history of UTIs or structural abnormalities and are characterized by recent onset of mild to moderate symptoms. Infection of the urinary tract is one of the most common diagnoses seen in primary care, and the most frequent urologic disorder encountered.4 These infections are responsible for more than 7 million office visits yearly in the United States, with costs exceeding $1 billion per year.5 UTIs are a particular problem in certain patient groups, with young, sexually active women and elderly individuals being disproportionately affected.4 Fifty percent of women have reported having at least one UTI by age 32. There are 1000 to 4000 cases of UTI per 100,000 females annually, and fewer than 100 cases per 100,000 men.6 Most of these infections are sporadic, with about 25% being recurrent infections.1 Over 33% of infections in long-term care facilities are attributed to UTIs, and UTI is one of the most common diagnoses in older adults.7,8 The risk of having a UTI in childhood is 2% in boys and 8% in girls. Uncircumcised boys younger than 6 months are at a higher risk to have a UTI than circumcised boys in the same age group.9 Overall, 3% to 8% of girls and 1% to 2% of boys will have a UTI.4 UTIs are unusual in men younger than 50 years with normal urologic structures but become more common with age. Common reasons for UTIs in men include prostatitis, epididymitis, orchitis, pyelonephritis, cystitis, and urethritis. Risk factors associated with UTI in men include previous UTI; enlarged prostate; history of instrumentation, catheterization, or surgery of the urinary tract; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; comorbidities; immunosuppression; abnormalities or family history of abnormalities in the urinary tract; and anal intercourse.10 After the age of 65 years, the incidence of UTIs in men is about 10%, whereas the incidence is 20% in similarly aged women.11 Asymptomatic bacteriuria refers to a colony count of at least 100,000/mL in the absence of symptoms. It is estimated that 8% of women have asymptomatic bacteriuria.2 It is more common in women, increases in both sexes with advancing age, and is found in as many as 43% of older women and 21% of older men, especially those living in nursing homes. In addition to advancing age and nursing home residence, asymptomatic bacteriuria is also associated with pregnancy, history of indwelling catheterization, instrumentation, urinary incontinence, diabetes, multiple medical illnesses, obstructive uropathy, postmenopausal status, and impaired functional and mental status.12 Most UTIs in women are secondary to ascending infection from the periurethral or perianal area. Bacteria from the colon, vagina, or skin are the usual organisms causing the infection.13 Cystitis is more common in women than in men because of the short length of the urethra and the proximity of the urethral opening and vagina to the perianal area. Bacteria reach the bladder through the urethra and have the opportunity to ascend to the kidneys through the ureters.14 A relatively narrow spectrum of microorganisms cause the majority of UTIs. The most prominent pathogens are gram-negative organisms including Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. E. coli represents 75% to 95% of infections in the bladder and ureters in normal genitourinary tracts. Staphylococcus saprophyticus is a species of gram-positive bacteria responsible for about 5% to 10% of uncomplicated bacterial UTIs.10 Nosocomial infections are caused by E. coli about 50% of the time; 40% of occurrences are caused by Klebsiella, Proteus, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas, and Serratia aeruginosa; 10% are caused by Enterococcus faecalis, S. saprophyticus, and Staphylococcus aureus. Pseudomonas is responsible for most UTIs found in catheterized patients.10,13 See Table 153-1 for a tabular representation of the causes of UTI. Most UTIs in women are not associated with complicating conditions or serious problems. Common precipitants include sexual intercourse, use of spermicidal agents, impaired voiding, recent antibiotic use, and estrogen deficiency. UTIs frequently occur in individuals with diabetes, obesity, urinary tract calculi, sickle cell trait, and frequent or indwelling bladder catheterization.6 In men, the reservoirs of microorganisms are not in close proximity to the urethral opening as in women; anatomic abnormalities of the urinary tract are more likely associated with UTIs in men. Risk factors associated with UTI in men include lack of circumcision, anal intercourse, HIV infection, and prostatic hypertrophy.15 Urethritis is characterized by an inflammation (mechanical, chemical, viral, or bacterial) of the urethra. Nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) is most common, with Chlamydia being the most frequent causative organism. Other urethral pathogens include Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus, and, in women, Trichomonas vaginalis and Gardnerella vaginalis. Noninfectious causes include Stevens-Johnson syndrome, Wegener granulomatosis, use of spermicides, and ingestion of some acidic foods.12 Risk factors for urethritis include being a man aged 20 to 35, being a female of reproductive age, having multiple sexual partners, engaging in high-risk sexual behavior, and having a history of a sexually transmitted disease (STD).15 Children’s bladders hold a small quantity of urine compared with an adult. Constipation is a greater risk factor for UTI in children, because hard stool may further reduce the capacity of the bladder and/or restrict the flow of urine. Bacteria have a better opportunity to grow in these conditions.9 Risk factors for UTIs are listed in Boxes 153-1 and 153-2. UTIs can be subdivided into several distinct classifications: uncomplicated, complicated, isolated, unresolved, reinfection, and relapse. Different characteristics are associated with each of these categories. Uncomplicated UTIs are characterized by signs and symptoms of bladder irritation: increased frequency, urgency, dysuria, suprapubic pain, odorous urine, and occasionally hematuria. The term uncomplicated infection implies that this is a relatively uncommon occurrence in the affected individual who is also otherwise healthy, that there are a small number of responsible pathogens susceptible to first-line narrow-spectrum antimicrobial agents, and that there are no underlying urologic or gynecologic abnormalities. A more acute presentation, including high fever, chills, flank pain, costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness, nausea, and vomiting, is suggestive of complicated UTI (pyelonephritis or urosepsis). A sustained bladder infection increases the risk for a complicated infection. However, kidney infection may also manifest with only bladder irritation and the absence of any of the classic signs or symptoms. Pyuria in the presence of positive urine or blood culture is indicative of a complicated UTI. Risks associated with complicated UTI include presence of urinary catheter, residual urine of 100 mL or more after voiding, obstruction in the urinary tract, azotemia resulting from kidney disease, and urinary retention.3 UTI is considered isolated with the first occurrence or a repeat occurrence at least 6 months from the previous episode. About 25% to 40% of infections are considered isolated. Unresolved infections persist when prescribed medications are not effective because of drug resistance or the presence of more than one organism with different drug sensitivities.2 UTIs are considered recurrent if they occur at least three times in 1 year or twice in 6 months.4 There are two basic patterns of recurrence: relapse and reinfection. Relapse refers to infection caused by bacterial persistence—infection by the previously treated pathogen, which was not completely eradicated by the course of antimicrobial therapy. Reinfection refers to recurrence of infection by introduction of a new bacterial strain or regrowth of the same organism after complete eradication with treatment. Recurrent UTIs in women are usually are a result of reinfection rather than relapse, but it is difficult to determine reinfection versus relapse.16 Groups often bothered by recurrent infections are listed in Table 153-2.2 TABLE 153-2 Outpatient Oral Antibiotic Treatment Regimens for Acute Bacterial Urinary Tract Infection in Nonpregnant Adults In men, symptoms of urethritis are usually mild and gradual in onset and include dysuria and irritative symptoms, frequency, urethral discharge, and pruritus at the distal end of the penis. Women may experience vaginal discharge or bleeding from concomitant cervicitis and lower abdominal pain. Urinalysis often demonstrates pyuria and less commonly, hematuria. Urine cultures generally show a colony count of less than 100/mL in urethritis. Important history to elicit from the woman with complaints of UTI symptoms includes urinary frequency, nocturia, dysuria, pruritus, fever or chills, hematuria, vaginal discomfort or discharge, pelvic discomfort, back or flank pain, date of last menstrual period, any prior history of UTIs, cervicitis, or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Patients should be queried about medical history, specifically immunocompromising disease or drugs, and recent instrumentation. A recent study has shown that women with a history of UTI correctly diagnose themselves (as confirmed by urine culture) as having a UTI 61% to 90% of the time.17 Vaginal symptoms, external irritation on urination, and dyspareunia are helpful in sorting out vaginal causes from those referable to the urinary tract. Male patients should be asked about urethral discharge, penile lesions, history of UTIs or sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and prior treatment. It is important to ask all patients about sexual history and risk factors for gonorrhea or chlamydia, including new or symptomatic sex partners. The physical examination should include assessment of vital signs, signs and symptoms of acute illness, and dehydration. A careful abdominal examination including the assessment of CVA tenderness is an important aspect of the physical examination. A pelvic examination in females should be performed if there is any indication that infection is not solely associated with the urinary tract. The vulva, vagina, cervix, periurethral area, and perianal area should be assessed for discharge, excoriations, tenderness, and ulcerations. In male patients, the penis should be checked for discharge, lesions, ulcerations, and swelling. The prostate should be checked for tenderness, swelling, masses, or nodules. A rectal examination showing a tender prostate may be indicative of acute prostatitis, and a normal or enlarged prostate indicates chronic bacterial prostatitis. The presence of cloudy urine, dysuria, and nocturia in women has shown a positive predictive value of greater than 80% for presence of UTI.18 Approximately half of women with one UTI symptom actually have the infection.4 Malodorous urine is not found to be indicative of infection.18 The diagnosis of UTI is suggested by the history and physical examination findings and confirmed by examination of the urine. The urinalysis is the most important initial study, with a urine dipstick as a reasonable rapid diagnostic aid. A clean-voided specimen minimizes contamination from nearby sources. Leukocyte esterase reflects the presence of white blood cells (WBCs) in the urine, but not all UTIs are associated with WBCs in the urine. Evidence-based guidelines from the University of Michigan Quality Management Program report that the presence of pyuria has a sensitivity of 80% to 90% and a specificity of 50% in predicting UTI. The nitrite test is not as good at detecting UTI; not all bacteria produce nitrate reductase, and false-positive results may occur with intake of ascorbic acid.5 However, in a more recent study of older women, these dipstick findings only resulted in 57% with a positive urine culture.19 In addition to leukocyte esterase and urinary nitrite, the presence of blood on the dipstick is another variable that is useful in predicting the presence of a UTI. In a study on the sensitivity and specificity of dipstick variables, the presence of nitrites was most predictive, followed by leukocytes with blood.20 Urine may also be examined microscopically, which allows easier detection of red blood cells, WBCs, bacteria, and WBC casts. Correlation with subsequent culture is approximately 90%. This diagnostic is typically ordered by the provider and performed by a laboratory before culturing. Abnormalities of pH, protein, and blood are nonspecific with respect to UTIs. In the presence of symptoms but a negative dipstick result, direct demonstration by microscopy or culture should be done before the possibility of infection is excluded. Urine culture is the definitive test; specimens should be obtained from all patients who are pregnant, are febrile, are seriously ill, have a history of frequent UTIs, live in a community with high rates of antibiotic resistance, or have recently been hospitalized, or in whom empirical treatment has failed.21 Cultures should be obtained in young men because these infections are unusual and suggestive of underlying problems. The presence of multiple bacterial species identified by culture usually suggests contamination of the specimen, except in the case of catheterization or other special circumstances. Small numbers of certain pathogens, including Klebsiella organisms and E. coli, should be regarded as suspicious. Large numbers of skin flora, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, diphtheroids, and β-hemolytic streptococci, can usually be ignored. Anaerobic bacteria do not usually cause UTIs; their presence suggests communication from the bowel. Candida organisms usually suggest vaginal contamination. Sterile pyuria is defined as a negative urine culture despite a positive urinalysis (e.g., positive leukocyte esterase). This condition requires further investigation because the absence of pathogens on culture does not imply the absence of infection. Renal tuberculosis, systemic illness, vaginal contamination, and kidney stones can also cause leukocytosis in the absence of a positive culture. Some infectious organisms, such as those causing NGU, do not grow on standard laboratory media. Cultures specific for these organisms should be considered if the history and physical examination findings suggest a chlamydial or nongonococcal cause. However, many patients with urethral syndrome do not have a demonstrable infectious agent even when special culture media are used. Test of cure urine cultures should be obtained in men and whenever there is suspicion that an infection may not have been eradicated. Routine test of cure cultures are not indicated unless a persistent UTI is suspected. The recurrence of a UTI within 2 weeks is suggestive of a persistent UTI.22 Renal ultrasound is useful to diagnose structural abnormalities, calculi, masses, and hydronephrosis. Persistent UTIs require more extensive urologic evaluation with referral to a urologist. Indications for ultrasound evaluation of patients with UTIs include frequent recurrent UTIs in females or failure to eradicate infection despite appropriate therapy; acute pyelonephritis in males; recurrent pyelonephritis in females; and palpable bladder or renal mass. Ultrasound is recommended for children younger than 2 years with their first febrile UTI, patients of any age with recurrent febrile UTIs, patients with a family history of kidney or urologic problems, and children with high blood pressure or retarded growth.23 The differential diagnosis of an acute uncomplicated UTI includes urethritis, vaginal infections, STIs that may lead to cervicitis or PID, and other STIs that may mimic symptoms of UTI but are considered distinct from UTIs. The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of the history, presenting signs and symptoms, and findings on urinalysis and culture. In the case of a negative urine dipstick result in the presence of urinary symptoms, microscopic evaluation or culture should be performed before it is decided that a UTI is not present. The combination of cervical discharge, cervical motion tenderness, and adnexal tenderness suggests cervicitis or PID. Atrophic vaginitis should be considered in a postmenopausal woman not using topical estrogen therapy. Chlamydial and gonorrheal cultures should be obtained in sexually active individuals. Clinical syndromes in women that mimic UTIs include acute urethral syndrome (also referred to as symptomatic abacteriuria) and interstitial cystitis. Clinical presentation is characterized by bladder irritation, frequency, urgency, and dysuria. The urinalysis is often unimpressive, with few leukocytes, no bacteria, and occasionally hematuria. Urine cultures show no significant colony counts, and urethral cultures are often negative. Symptoms of interstitial cystitis also include suprapubic discomfort, especially with a full bladder, and symptoms are often relieved with voiding. No definitive therapy for interstitial cystitis has been developed. The differential diagnoses for chronic or recurrent UTIs include structural abnormalities (such as obstructive uropathy, congenital anomalies, urinary tract fistulas), neurologic dysfunction, renal calculi and renal masses, intrarenal and perirenal abscesses, bladder tuberculosis, and prostate enlargement in men. Indications for urology referral include presence of macroscopic hematuria, suspected malignancy, recurrent UTIs or infections that do not respond to standard antimicrobial therapy, urinary tract anomalies or obstructions, acute scrotum, and all forms of prostatitis. Hospitalization is recommended for pregnant women with pyelonephritis.24 1. Uncomplicated UTIs are typically managed on an outpatient basis with oral antibiotics. Recommended antimicrobials for treatment of UTI are shown in Table 153-2.25 3. UTI in pregnancy: see Table 153-3 for antimicrobial choices. TMP-SMX is no longer recommended for UTI in pregnancy because it is pregnancy risk factor D and may be associated with increased risk of congenital malformations.26 TABLE 153-3 Oral Antibiotic Treatment Options for Urinary Tract Infection During Pregnancy 4. UTIs in children are commonly treated with the antimicrobials. 6. The effectiveness of specific nonpharmacologic therapies, especially cranberry juice, is still unclear, although the consensus of the lay public is that cranberry juice is helpful in treating and preventing UTIs. A recent literature review (2013) found insufficient evidence to recommend the use of cranberry juice for management of UTI.27 7. Recurrent cystitis can be managed by one of several strategies: continuous prophylaxis, postcoital prophylaxis, or therapy initiated by the patient. Prophylaxis should not be initiated until the existing UTI has been eradicated, confirmed with negative culture 1 to 2 weeks after treatment. Recommended antibiotics include TMP-SMX, nitrofurantoin, cephalexin, trimethoprim, or a quinolone.28 The most common complication of UTI is pyelonephritis, a bacterial infection of the kidney resulting from ascending, untreated or inadequately treated lower UTI. Pyelonephritis can be treated effectively on an outpatient basis, and clinical response should occur within 48 to 72 hours of starting therapy. If no improvement is noted or if the patient’s condition worsens, aggressive investigation for complications of renal infection or urinary obstruction should be undertaken, which generally requires hospitalization. Acute pyelonephritis is the most common serious medical complication of pregnancy, and 1% to 2% of pregnant women are admitted for this condition despite perinatal screening and treatment for bacteriuria.29 Urosepsis is a potentially life-threatening systemic complication of UTI that requires hospitalization with high-dose parenteral antimicrobial therapy. Acute urinary infections may be associated with severe complications and even death, particularly in patients with underlying comorbidities such as diabetes and in those with indwelling urologic devices or chronic disease. Individuals with diabetes are also more likely to develop rare complications, such as emphysematous cystitis and pyelonephritis, abscess formation, and renal papillary necrosis, compared with those who do not have diabetes mellitus. Any patient who appears acutely ill or with signs and symptoms of obstruction or urosepsis requires immediate hospitalization. Specific signs and symptoms requiring consideration for hospitalization or referral include rigors, high fever, flank pain, nausea, and vomiting. Older adults and those with acute, severe symptoms are candidates for hospitalization and often require parenteral therapy. A history of diabetes mellitus, sickle cell anemia, nephrolithiasis, or excessive analgesic use increases the risk of renal papillary necrosis and subsequent obstruction and can be considered an indication for hospitalization. Asymptomatic UTIs are more prevalent in pregnant women. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening at the first prenatal visit or at 12 to 16 weeks’ gestation with urine culture. Prompt treatment of infection is indicated in these women to decrease the risk of acute pyelonephritis, premature delivery, and low birth weight.21 UTIs are the most common cause of bacterial infection in older adults but are often not accompanied by the classic signs and symptoms. Symptoms are often subtle and may include a vague change in mental status, decreased appetite, lethargy, and increased falls (sustained during efforts to get to the bathroom). UTIs are also the most common cause of sepsis, the second most common cause of bacteremia in the geriatric population, and an important cause of morbidity and mortality in nursing facilities.30 Nonpharmacologic measures have been demonstrated to prevent episodic or recurrent UTIs. Sexual intercourse and failure to void within 10 to 15 minutes after coitus are two factors most consistently associated with UTIs. In discussing the association between these two factors and UTIs with a patient, the provider must distinguish between UTIs and STIs. Drinking plenty of fluids (64 to 80 ounces daily), urinating frequently (at least every 4 hours), wiping from front to back, and using tampons during menstruation may also be helpful in preventing UTIs. Avoiding the following will help in the prevention of UTIs: using of sanitary napkins during menstruation, wiping more than once with the same tissue, extended soaking in a bathtub, wearing tight-fitting underwear made of nonbreathable fabric, and using spermicidal products. Women who have had previous UTIs should be encouraged to seek treatment as soon as symptoms are recognized.31 Women with recurrent UTIs should be educated about the possible benefits of antimicrobial suppression or postcoital prophylaxis, depending on the situation. Intravaginal estrogen cream may be helpful for postmenopausal women with recurrent UTIs. Patients should be informed that no reliable evidence is available showing that cranberry ingestion is associated with prevention of UTIs.32 The terms sexually transmitted infection and sexually transmitted disease are used interchangeably. They encompass more than 25 infectious organisms that are transmitted through sexual activity along with the dozens of clinical syndromes associated with these organisms. The most common STIs in the United States, from highest number of new occurrences to lowest, are human papillomavirus (HPV), chlamydia, trichomoniasis, gonorrhea, genital herpes, syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis B.33,34 HPV, trichomoniasis, HIV, and hepatitis B are discussed elsewhere in this book. STIs are spread by anal, oral, or vaginal sex with an infected individual. Symptoms are not always present, and knowing if sexual partners are infected can be challenging.35 Pregnant women infected with an STI may infect infants in utero or during birth; women may also infect infants through breastfeeding. There are approximately 20 million new cases of STIs annually in the United States, which cost the U.S. health care system $16 billion annually.34 The latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveillance report states that there has been an increase of 4.1% in gonorrhea and 0.7% in chlamydia cases reported in 2011 to 2012. Chlamydia is one of the most widespread STIs in the United States. Reported syphilis cases rose 11% in 2011 to 2012 after remaining stable in 2010 to 2011. The number of cases of congenital syphilis (transmitted from mother to infant) are at the lowest rate since 1988. The CDC’s surveillance report includes data on only those STIs (syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea) for which there is mandatory reporting, underestimating the true prevalence of STIs.36 STIs affect males and females of all racial, cultural, and socioeconomic groups, but wide disparities are present. The CDC’s data show much higher rates of reported STIs among certain racial and ethnic groups, with blacks being disproportionally affected by chlamydia, gonorrhea, and primary and secondary syphilis. Figure 153-1 shows a graphical representation of the racial distribution of gonorrhea and chlamydia. Many factors contribute to this disparity, including poverty, lack of access to health care, and a relatively high prevalence of STIs in the community.36

Urinary Tract Infections and Sexually Transmitted Infections

Urinary Tract Infections

Definition and Epidemiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical Presentation

Antimicrobial Agent

Dose (Uncomplicated Infection)

Dose (Complicated Infection)*

Nitrofurantoin monohydrate, macrocrystals

100 mg twice daily for 5 days

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX)

1 double-strength tab 160 mg TMP/800 mg SMX twice daily for 3 days (avoid if used within last 3 months, or >20% resistance)

1 double-strength tab, 160 mg TMP/800 mg SMX twice daily for 14 days

Fosfomycin tromethamine

3 g, single dose

Ciprofloxacin

250 mg twice daily for 3 days†

500 mg twice daily for 7 days

Levofloxacin

250 mg once daily for 3 days†

750 mg once daily for 5 days

Ofloxacin

200 mg twice daily for 3 days†

200 mg twice daily for 10 days

Physical Examination

Diagnostics

Differential Diagnosis

Management

![]() Specialist referral is indicated for complicated UTIs; consideration to hospitalize should be discussed.

Specialist referral is indicated for complicated UTIs; consideration to hospitalize should be discussed.

Antibiotic

Pregnancy Category

Dose

Amoxicillin

B

500 mg, twice daily for 7 days

Amoxicillin-clavulanate

B

500/125 mg twice daily for 7 days

Fosfomycin tromethamine

B

3 g in single dose

Cefuroxime

B

250 mg twice daily for 7 days

Cephalexin

B

500 mg twice daily for 7 days

Nitrofurantoin monohydrate/macrocrystals

B (avoid during first trimester)26

X (38-42 weeks’ gestation)

100 mg twice daily for 7 days

Complications

Indications for Referral or Hospitalization

Life Span Considerations

Patient and Family Education

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Definition and Epidemiology

Urinary Tract Infections and Sexually Transmitted Infections

Chapter 153