Section 1 – Introduction

Ultrasound (US) has become an integral modality in emergency care in the United States during the last two decades. Since the last update of these guidelines in 2008, US use has expanded throughout clinical medicine and established itself as a standard in the clinical evaluation of the emergency patient. There is a wide breadth of recognized emergency US applications offering advanced diagnostic and therapeutic capability benefit to patients across the globe. With its low capital, space, energy, and cost of training requirements, US can be brought to the bedside anywhere a clinician can go, directly or remotely. The use of US in emergency care has contributed to improvement in quality and value, specifically in regards to procedural safety, timeliness of care, diagnostic accuracy, and cost reduction. In a medical world full of technological options, US fulfills the concept of “staged imaging,” where the use of US first can answer important clinical questions accurately without the expense, time, or side effects of advanced imaging or invasive procedures.

Emergency physicians have taken the leadership role for the establishment and education of bedside, clinical, point-of-care US use by clinicians in the United States and around the world. Ultrasonography has spread throughout all levels of medical education, integrated into medical school curricula, through residency, to postgraduate education of physicians, and extended to other providers such as nursing, advanced practice professionals, and prehospital providers. US curricula in undergraduate medical education is growing exponentially due to the leadership and advocacy of emergency physicians. US in emergency medicine (EM) residency training has now been codified in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Next Accreditation System (NAS). Emergency US specialists have created the foundation of a subspecialty of ultrasonography that provides the expertise for establishing clinical practice, educating across the educational spectrum, and researching the wide range of applications of ultrasonography. Within healthcare institutions and healthcare systems, emergency physicians are now leading institutional clinical US programs that have used this guideline as a format for multidisciplinary programs.

US imaging and information systems have become more sophisticated and digital over the last decade allowing emergency US examinations to have versatility, mobility and integration. US hardware for emergency care has become more modular, smaller, and powerful, ranging from smartphone size to slim, cart-based systems dedicated to the emergency medicine market. US hardware has evolved to allow on-machine reporting, wireless connectivity and electronic medical record (EMR) and picture archiving and communication system (PACS) integration. A new software entity, US management systems, was created to provide administrative functionality and the integration of US images into electronic records. Emergency physician expertise was integral in the development of these hardware and software advances.

These guidelines reflect the evolution and changes in the evolving world of emergency medicine and the growth of US practice. Themes of universality of practice, educational innovation, core credentialing, quality improvement, and value highlight this new edition of the guidelines. The ultimate mission of providing excellent patient care will be enhanced by emergency physicians and other clinicians being empowered with the use of US.

Section 2- Scope of Practice

Emergency Ultrasound (EUS) is the medical use of US technology for the bedside evaluation of acute or critical medical conditions. It is utilized for diagnosis of any emergency condition, resuscitation of the acutely ill, critically ill or injured, guidance of procedures, monitoring of certain pathologic states and as an adjunct to therapy. EUS examinations are typically performed, interpreted, and integrated into care by emergency physicians or those under the supervision of emergency physicians in the setting of the emergency department (ED) or a non-ED emergency setting such as hospital unit, out-of-hospital, battlefield, space, urgent care, clinic, or remote or other settings. It may be performed as a single examination, repeated due to clinical need or deterioration, or used for monitoring of physiologic or pathologic changes.

Emergency US is synonymous with the terms clinical, bedside, point-of-care, focused, and physician performed, but is part of a larger field of clinical ultrasonography. In this document, EUS refers to US performed by emergency physicians or clinicians in the emergency setting, while clinical ultrasonography refers to a multidisciplinary field of US use by clinicians at the point-of-care. Table 1 summarizes relevant US definitions in EUS.

| Resuscitative | US use directly related to a resuscitation |

| Diagnostic | US utilized a diagnostic imaging capacity |

| Symptom or sign-based | US used in a clinical pathway based upon the patient’s symptoms or sign (eg, shortness of breath) |

| Therapeutic and Monitoring | US use in therapeutics or physiological monitoring |

| Procedural guidance | US used as an aid to guide a procedure |

| Consultative Ultrasound | A written or electronic request for an US examination & interpretation for which the patient is transported to a laboratory or imaging department outside of the clinical setting. |

| Emergency Ultrasound | Performed and interpreted by the provider as an emergency procedure and directly integrated into the care of the patient |

| Clinical Ultrasound | US used in the clinical setting, distinct from the physical examination, that adds anatomic, functional and physiologic information to the care of the acutely ill patient. |

| Educational Ultrasound | US performed in a non-clinical setting by medical students or other clinician trainees to enhance physical examination skills. Exams usually performed on cadavers or live models. |

Other medical specialties may wish to use this document if they perform EUS in the manner described above. However, guidelines which apply to US examinations or procedures performed by consultants, especially consultative imaging in US laboratories or departments, or in a different setting may not be applicable to emergency physicians.

Emergency US is an emergency medicine procedure, and should not be considered in conflict with exclusive “imaging” contracts that may be in place with consultative US practices. In addition, emergency US should be reimbursed as a separate billable procedure. (See Section 6- Value and Reimbursement )

EUS is a separate entity distinct from the physical examination that adds anatomic, functional, and physiologic information to the care of the acutely-ill patient. It provides clinically significant data not obtainable by inspection, palpation, auscultation, or other components of the physical examination. US used in this clinical context is also not equivalent to use in the training of medical students and other clinicians in training looking to improve their understanding of anatomic and physiologic relationships of organ systems.

EUS can be classified into the following functional clinical categories:

- 1.

Resuscitative : US use as directly related to an acute resuscitation

- 2.

Diagnostic : US utilized in an emergent diagnostic imaging capacity

- 3.

Symptom or sign-based : US used in a clinical pathway based upon the patient’s symptom or sign (eg, shortness of breath)

- 4.

Procedure guidance : US used as an aid to guide a procedure

- 5.

Therapeutic and Monitoring : US use in therapeutics or in physiological monitoring

Within these broad functional categories of use, 12 core emergency US applications have been identified as Trauma, Pregnancy, Cardiac /Hemodynamic assessment, Abdominal aorta, Airway/Thoracic, Biliary, Urinary Tract, Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT), Soft-tissue/Musculoskeletal (MSK), Ocular, Bowel, and Procedural Guidance. Evidence for these core applications may be found in Appendix 1 . The criteria for inclusion for core are widespread use, significant evidence base, uniqueness in diagnosis or decisionmaking, importance in primary emergency diagnosis and patient care, or technological advance.

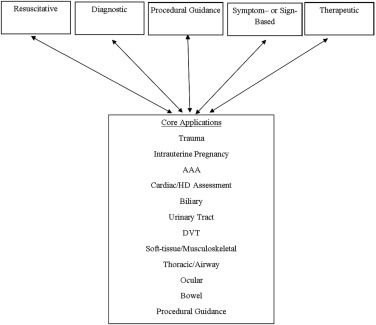

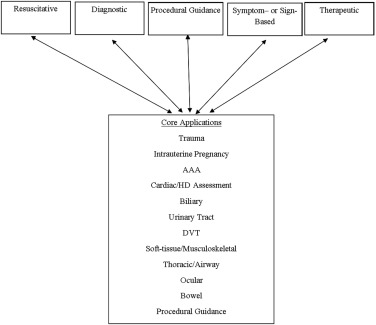

Alternatively, symptom and sign based US pathways, such as Shock or Dyspnea, may be considered an integrated application based on the skills required in the pathway. In such pathways, applications may be mixed and utilized in a format and order that maximizes medical decisionmaking, outcomes, efficiency and patient safety tailored to the setting, resources, and patient characteristics. See Figure 1 .

Emergency physicians should have basic education in US physics, instrumentation procedural guidance, and Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) as part of EM practice. It is not mandatory that every clinician performing emergency US examinations utilize or be expert in each core application, but it is understood that each core application is incorporated into common emergency US practice nationwide. The descriptions of these examinations may be found in the ACEP policy, Emergency Ultrasound Imaging Criteria Compendium. Many other US applications or advanced uses of these applications may be used by emergency physicians. Their non-inclusion as a core application does not diminish their importance in practice nor imply that emergency physicians are unable to use them in daily patient care.

Each EUS application represents a clinical bedside skill that can be of great advantage in a variety of emergency patient care settings. In classifying an emergency US a single application may appear in more than one category and clinical setting. For example a focused cardiac US may be utilized to identify a pericardial effusion in the diagnosis of an enlarged heart on chest x-ray. The focused cardiac US may be utilized in a cardiac resuscitation setting to differentiate true pulseless electrical activity from profound hypovolemia. The focused cardiac US can be used to monitor the heart during resuscitation in response to fluids or medications. If the patient is in cardiac tamponade, the cardiac US can also be used to guide the procedure of pericardiocentesis. In addition, the same focused cardiac study can be combined with one or more additional emergency US types, such as the focused abdominal, the focused aortic or the focused chest US, into a clinical algorithm and used to evaluate a presenting symptom complex. Examples of this would be the evaluation of patients with undifferentiated non-traumatic shock or the focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST), or extended FAST examination in the patient presenting with traumatic injury. See Figure 1 .

Ultrasound guided procedures provide safety to a wide variety of procedures from vascular access (eg, central venous access) to drainage procedures (eg, thoracentesis pericardiocentesis, paracentesis, arthrocentesis) to localization procedures like US guided nerve blocks. These procedures may provide additional benefits by increasing patient safety and treating pain without the side effects of systemic opiates.

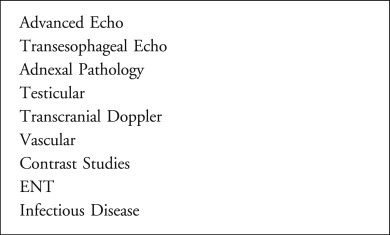

Other US applications are performed by emergency physicians, and may be integrated depending on the setting, training, and needs of that particular ED or EM group. Figure 2 lists other emergency US applications.

Other Settings or Populations

Pediatrics

US is a particularly advantageous diagnostic tool in the management of pediatric patients, in whom radiation exposure is a significant concern. EUS applications such as musculoskeletal evaluation for certain fractures (rib, forearm, skull), and lung for pneumonia may be more advantageous in children than in adults due to patient size and density. US can be associated with increased procedural success and patient safety, and decreased length of stay. While most US modalities in the pediatric arena are the same as in adult patients (the EFAST exam for trauma, procedural guidance), other modalities are unique to the pediatric population such as in suspected pyloric stenosis and intussusception, or in the child with hip pain or a limp). Mostly recently, EUS has been formally incorporated into Pediatric EM fellowship training.

Critical Care

EUS core applications are being integrated into cardiopulmonary and non-invasive hemodynamic monitoring into critical care scenarios. Dual-trained physicians in emergency medicine and critical care are leading the application, education, and research of US for critically ill patients, and have significant leadership in advancing US concepts in multidisciplinary critical care practice. Advanced cardiopulmonary US applications are being integrated into critical care practice.

Prehospital

There is increasing evidence that US has an increasing role in out-of-hospital emergency care. Challenges to the widespread implementation of out-of-hospital US include significant training and equipment requirements, and the need for careful physician oversight and quality assurance. Studies focusing on patient outcomes need to be conducted to further define the role of out-of-hospital US and to identify settings where the benefit to the patient justifies the investment of resources necessary to implement such a program.

International arena including field, remote, rural, global public health and disaster situations

US has become the primary initial imaging modality in disaster care. US can direct and optimize patient care in domestic and international natural disasters such as tsunami, hurricane, famine or man-made disasters such as battlefield or refugee camps. US provides effective advanced diagnostic technology in remote geographies such as rural areas, developing countries, or small villages which share the common characteristics of limited technology (ie, x-ray, CT, MRI), unreliable electrical supplies, and minimally trained health care providers. US use in outer space is unique as the main imaging modality for space exploration and missions. Ultrasound has also been used in remote settings such as international exploration, mountain base camps, and cruise ships. The increasing portability of US machines with increasing image resolution has expanded the use of emergent imaging in such settings. See ACEP linked resources at www.globalsono.org .

Military and Tactical

The military has embraced the utilization of US technology in austere battlefield environments. It is now routine for combat support hospitals as well as forward surgical teams to deploy with next generation portable ultrasonography equipment. Clinical ultrasonography is often used to inform decisions on mobilization of causalities to higher echelons of care and justify use of limited resources.

Within the last decade, emergency physicians at academic military medical centers have expanded ultrasonography training to clinical personnel who practice in close proximity to the point of injury, such as combat medics, special operations forces, and advanced practice professionals. The overarching goal of these training programs is to create a generation of competent clinical sonologists capable of practicing “good medicine in bad places.” The military is pursuing telemedicine-enabled US applications, automated US interpretation capabilities, and extension of clinical ultrasonography in additional areas of operation, such as critical care air evacuation platforms.

Section 2- Scope of Practice

Emergency Ultrasound (EUS) is the medical use of US technology for the bedside evaluation of acute or critical medical conditions. It is utilized for diagnosis of any emergency condition, resuscitation of the acutely ill, critically ill or injured, guidance of procedures, monitoring of certain pathologic states and as an adjunct to therapy. EUS examinations are typically performed, interpreted, and integrated into care by emergency physicians or those under the supervision of emergency physicians in the setting of the emergency department (ED) or a non-ED emergency setting such as hospital unit, out-of-hospital, battlefield, space, urgent care, clinic, or remote or other settings. It may be performed as a single examination, repeated due to clinical need or deterioration, or used for monitoring of physiologic or pathologic changes.

Emergency US is synonymous with the terms clinical, bedside, point-of-care, focused, and physician performed, but is part of a larger field of clinical ultrasonography. In this document, EUS refers to US performed by emergency physicians or clinicians in the emergency setting, while clinical ultrasonography refers to a multidisciplinary field of US use by clinicians at the point-of-care. Table 1 summarizes relevant US definitions in EUS.

| Resuscitative | US use directly related to a resuscitation |

| Diagnostic | US utilized a diagnostic imaging capacity |

| Symptom or sign-based | US used in a clinical pathway based upon the patient’s symptoms or sign (eg, shortness of breath) |

| Therapeutic and Monitoring | US use in therapeutics or physiological monitoring |

| Procedural guidance | US used as an aid to guide a procedure |

| Consultative Ultrasound | A written or electronic request for an US examination & interpretation for which the patient is transported to a laboratory or imaging department outside of the clinical setting. |

| Emergency Ultrasound | Performed and interpreted by the provider as an emergency procedure and directly integrated into the care of the patient |

| Clinical Ultrasound | US used in the clinical setting, distinct from the physical examination, that adds anatomic, functional and physiologic information to the care of the acutely ill patient. |

| Educational Ultrasound | US performed in a non-clinical setting by medical students or other clinician trainees to enhance physical examination skills. Exams usually performed on cadavers or live models. |

Other medical specialties may wish to use this document if they perform EUS in the manner described above. However, guidelines which apply to US examinations or procedures performed by consultants, especially consultative imaging in US laboratories or departments, or in a different setting may not be applicable to emergency physicians.

Emergency US is an emergency medicine procedure, and should not be considered in conflict with exclusive “imaging” contracts that may be in place with consultative US practices. In addition, emergency US should be reimbursed as a separate billable procedure. (See Section 6- Value and Reimbursement )

EUS is a separate entity distinct from the physical examination that adds anatomic, functional, and physiologic information to the care of the acutely-ill patient. It provides clinically significant data not obtainable by inspection, palpation, auscultation, or other components of the physical examination. US used in this clinical context is also not equivalent to use in the training of medical students and other clinicians in training looking to improve their understanding of anatomic and physiologic relationships of organ systems.

EUS can be classified into the following functional clinical categories:

- 1.

Resuscitative : US use as directly related to an acute resuscitation

- 2.

Diagnostic : US utilized in an emergent diagnostic imaging capacity

- 3.

Symptom or sign-based : US used in a clinical pathway based upon the patient’s symptom or sign (eg, shortness of breath)

- 4.

Procedure guidance : US used as an aid to guide a procedure

- 5.

Therapeutic and Monitoring : US use in therapeutics or in physiological monitoring

Within these broad functional categories of use, 12 core emergency US applications have been identified as Trauma, Pregnancy, Cardiac /Hemodynamic assessment, Abdominal aorta, Airway/Thoracic, Biliary, Urinary Tract, Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT), Soft-tissue/Musculoskeletal (MSK), Ocular, Bowel, and Procedural Guidance. Evidence for these core applications may be found in Appendix 1 . The criteria for inclusion for core are widespread use, significant evidence base, uniqueness in diagnosis or decisionmaking, importance in primary emergency diagnosis and patient care, or technological advance.

Alternatively, symptom and sign based US pathways, such as Shock or Dyspnea, may be considered an integrated application based on the skills required in the pathway. In such pathways, applications may be mixed and utilized in a format and order that maximizes medical decisionmaking, outcomes, efficiency and patient safety tailored to the setting, resources, and patient characteristics. See Figure 1 .

Emergency physicians should have basic education in US physics, instrumentation procedural guidance, and Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) as part of EM practice. It is not mandatory that every clinician performing emergency US examinations utilize or be expert in each core application, but it is understood that each core application is incorporated into common emergency US practice nationwide. The descriptions of these examinations may be found in the ACEP policy, Emergency Ultrasound Imaging Criteria Compendium. Many other US applications or advanced uses of these applications may be used by emergency physicians. Their non-inclusion as a core application does not diminish their importance in practice nor imply that emergency physicians are unable to use them in daily patient care.

Each EUS application represents a clinical bedside skill that can be of great advantage in a variety of emergency patient care settings. In classifying an emergency US a single application may appear in more than one category and clinical setting. For example a focused cardiac US may be utilized to identify a pericardial effusion in the diagnosis of an enlarged heart on chest x-ray. The focused cardiac US may be utilized in a cardiac resuscitation setting to differentiate true pulseless electrical activity from profound hypovolemia. The focused cardiac US can be used to monitor the heart during resuscitation in response to fluids or medications. If the patient is in cardiac tamponade, the cardiac US can also be used to guide the procedure of pericardiocentesis. In addition, the same focused cardiac study can be combined with one or more additional emergency US types, such as the focused abdominal, the focused aortic or the focused chest US, into a clinical algorithm and used to evaluate a presenting symptom complex. Examples of this would be the evaluation of patients with undifferentiated non-traumatic shock or the focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST), or extended FAST examination in the patient presenting with traumatic injury. See Figure 1 .

Ultrasound guided procedures provide safety to a wide variety of procedures from vascular access (eg, central venous access) to drainage procedures (eg, thoracentesis pericardiocentesis, paracentesis, arthrocentesis) to localization procedures like US guided nerve blocks. These procedures may provide additional benefits by increasing patient safety and treating pain without the side effects of systemic opiates.

Other US applications are performed by emergency physicians, and may be integrated depending on the setting, training, and needs of that particular ED or EM group. Figure 2 lists other emergency US applications.

Other Settings or Populations

Pediatrics

US is a particularly advantageous diagnostic tool in the management of pediatric patients, in whom radiation exposure is a significant concern. EUS applications such as musculoskeletal evaluation for certain fractures (rib, forearm, skull), and lung for pneumonia may be more advantageous in children than in adults due to patient size and density. US can be associated with increased procedural success and patient safety, and decreased length of stay. While most US modalities in the pediatric arena are the same as in adult patients (the EFAST exam for trauma, procedural guidance), other modalities are unique to the pediatric population such as in suspected pyloric stenosis and intussusception, or in the child with hip pain or a limp). Mostly recently, EUS has been formally incorporated into Pediatric EM fellowship training.

Critical Care

EUS core applications are being integrated into cardiopulmonary and non-invasive hemodynamic monitoring into critical care scenarios. Dual-trained physicians in emergency medicine and critical care are leading the application, education, and research of US for critically ill patients, and have significant leadership in advancing US concepts in multidisciplinary critical care practice. Advanced cardiopulmonary US applications are being integrated into critical care practice.

Prehospital

There is increasing evidence that US has an increasing role in out-of-hospital emergency care. Challenges to the widespread implementation of out-of-hospital US include significant training and equipment requirements, and the need for careful physician oversight and quality assurance. Studies focusing on patient outcomes need to be conducted to further define the role of out-of-hospital US and to identify settings where the benefit to the patient justifies the investment of resources necessary to implement such a program.

International arena including field, remote, rural, global public health and disaster situations

US has become the primary initial imaging modality in disaster care. US can direct and optimize patient care in domestic and international natural disasters such as tsunami, hurricane, famine or man-made disasters such as battlefield or refugee camps. US provides effective advanced diagnostic technology in remote geographies such as rural areas, developing countries, or small villages which share the common characteristics of limited technology (ie, x-ray, CT, MRI), unreliable electrical supplies, and minimally trained health care providers. US use in outer space is unique as the main imaging modality for space exploration and missions. Ultrasound has also been used in remote settings such as international exploration, mountain base camps, and cruise ships. The increasing portability of US machines with increasing image resolution has expanded the use of emergent imaging in such settings. See ACEP linked resources at www.globalsono.org .

Military and Tactical

The military has embraced the utilization of US technology in austere battlefield environments. It is now routine for combat support hospitals as well as forward surgical teams to deploy with next generation portable ultrasonography equipment. Clinical ultrasonography is often used to inform decisions on mobilization of causalities to higher echelons of care and justify use of limited resources.

Within the last decade, emergency physicians at academic military medical centers have expanded ultrasonography training to clinical personnel who practice in close proximity to the point of injury, such as combat medics, special operations forces, and advanced practice professionals. The overarching goal of these training programs is to create a generation of competent clinical sonologists capable of practicing “good medicine in bad places.” The military is pursuing telemedicine-enabled US applications, automated US interpretation capabilities, and extension of clinical ultrasonography in additional areas of operation, such as critical care air evacuation platforms.

Section 3 – Training and Proficiency

There is an evolving spectrum of training in clinical US from undergraduate medical education through post-graduate training, where skills are introduced, applications are learned, core concepts are reinforced and new applications and ideas evolve in the life-long practice of US in emergency medicine.

Competency and Curriculum Recommendations

Competency in EUS requires the progressive development and application of increasingly sophisticated knowledge and psychomotor skills for an expanding number of EUS applications. This development parallels the performance of any EUS exam.

The ACEP definition of US competency includes the following components. First, the clinician needs to recognize the indications and contraindications for the EUS exam. Next, the clinician must be able to acquire adequate images. This begins with an understanding of basic US physics, translated into the skills needed to operate the US system correctly (knobology), while performing exam protocols on patients presenting with different conditions and body habitus. Simultaneous with image acquisition, the clinician needs to interpret the imaging by distinguishing between normal anatomy, common variants, as well as a range of pathology from obvious to subtle. Finally, the clinician must be able to integrate EUS exam findings into individual patient care plans and management. Ultimately, effective integration includes knowledge of each particular exam accuracy, as well as proper documentation, quality assurance, and EUS reimbursement. See ACEP linked resources at http://www.acep.org/sonoguide .

An EUS curriculum requires considerable faculty expertise, dedicated faculty time and resources, and departmental support. These updated guidelines continue to provide the learning objectives (See Appendix 2 ), educational methods, and assessment measures for any EUS residency or practice-based curriculum. As part of today’s effort to reinvent medical education, all educators are now faced with the challenge of creating curricula that provide for individualized learning yet result in the standardized outcomes such as those outlined in current residency milestones.

Innovative Educational Methods and Assessment Measures

As a supplement to traditional EUS education already described in previous guidelines, recent online and technological innovation is providing additional individualized educational methods and standardized assessment measures to meet this challenge. Free open access medical (FOAM) education podcasts and narrated lectures provide the opportunity to create the flipped EUS classroom. For the trainee, asynchronous learning provides the opportunity to repeatedly review required knowledge on demand and at their own pace. For educators, less time may be spent providing recurring EUS didactics, and more time dedicated to higher level tasks such as teaching psychomotor skills and integration of exam findings into patient and ED management. Both EUS faculty and trainees together may identify potential FOAM resources. However, EUS faculty must now take the new role of FOAM curator. New online resources must be carefully reviewed to ensure that each effectively teaches the objectives in these guidelines before being introduced into an EUS curriculum.

Similar to knowledge learning, there are new educational methods to teach the required psychomotor skills of EUS. The primary educational method continues to be small group hands-on training in the ED with EUS faculty, followed by supervised examination performance with timely quality assurance review. Simulation is currently playing an increasingly important role as both an EUS educational method and assessment measure. Numerous investigators have demonstrated that simulation results in equivalent image acquisition, interpretation, and operator confidence in comparison to traditional hands-on training. US simulators provide the opportunity for deliberate practice of a new skill in a safe environment prior to actual clinical performance. The use of simulation for deliberate practice improves the success rate of invasive procedures and reduces patient complications. Additionally, simulation has the potential to expose trainees to a wider spectrum of pathology and common variants than typically encountered during an EUS rotation. Blended learning created by the flipped classroom, live instructor training, and simulation provide the opportunity for self-directed learning, deliberate practice and mastery learning.

Simulation also provides a valid assessment measure of each component of EUS competency. Appropriately designed cases assess a trainee’s ability to recognize indications, demonstrate image acquisition and interpretation, as well as apply EUS findings to patient and ED management. These proven benefits and the reduction in direct faculty time justify the cost of a high fidelity US simulator. Furthermore, costs may be shared across departments.

Documenting Experience and Demonstrating Proficiency

Traditional number benchmarks for procedural training in medical education provide a convenient method for documenting the performance of a reasonable number of exams needed for a trainee to develop competency. However, learning curves vary by trainee and application. Individuals learn required knowledge and psychomotor skills at their own pace. Supervision, opportunities to practice different applications and encounter pathology also differ across departments.

Therefore, in addition to set number benchmarks individualized assessment methods need to be utilized. Recommended methods include the following: real time supervision during clinical EUS, weekly QA teaching sessions and image review, ongoing QA exam feedback, standardized knowledge assessments, small group Observed Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs), one-on-one standardized direct observation tools (SDOTs), simulation assessments and other focused educational tools. Ideally these assessment measures are completed both at the beginning and the end of a training period. Initial assessment measures identify each trainee’s unique needs, providing the opportunity to modify a local curriculum as needed to create more individualized learning plans. Final assessment measures demonstrate current trainee competency and future learning needs, as well as identify opportunities for improvement in local EUS education.

Trainees should complete a benchmark of 25-50 quality-reviewed exams in a particular application

It is acknowledged that the training curve may level out below or above this recommended threshold, and that learning is a lifelong process with improvements beyond initial training. Previously learned psychomotor skills are often applicable to new applications. For example, experience with FAST provides a springboard to learning resuscitation, genitourinary, and transabdominal pelvic EUS.

Overall EUS trainees should complete a benchmark of 150-300 total EUS exams depending on the number of applications being utilized

For example, an academic department regularly performing greater than six applications may require residents to complete more than 150 exams, while a community ED with practicing physicians just beginning to incorporate EUS with FAST and vascular access should require less.

If different modalities such as endovaginal technique are being used for an application, the minimum may need to include a substantial experience in that technique. We would recommend a minimum of 10 examinations in the other technique (eg, endocavitary for early pregnancy) with the assumption that educational goals of anatomic, pathophysiology, and abnormal states are identified with all techniques taught.

Procedural US applications require fewer exams given prior knowledge, psychomotor skills, and clinical experience with traditional blind technique. Trainees should complete five quality reviewed US-guided procedure examinations or a learning module on an US-guided procedures task trainer.

Training exams need to include patients with different conditions and body types. Exams may be completed in different settings including clinical and educational patients in the ED, live models at EUS courses, utilizing US simulators, and in other clinical environments. Abnormal or positive scans should be included in a significant number of training exams used to meet credentialing requirements. Image review or simulation may be utilized for training examinations in addition to patient encounters when adequate pathology is not available for the specific application. In-person supervision is optimal during introductory education but is not required for residency or credentialing examinations after initial didactic training.

During benchmark completion, all EUS exams should be quality reviewed for technique and accuracy by EUS faculty. Alternatively, an EUS training portfolio of exam images and results may be compared to other diagnostic studies and clinical outcomes in departments where EUS faculty are not yet available. After initial training, continued quality assurance of EUS exams is recommended for a proportion (5-10%) of ongoing exams to document continued competency.

Recently, several secure online quality assurance workflow systems have become commercially available (See Section 5- Quality and US Management ). Current systems greatly enhance trainee feedback by providing for more timely review of still images and video loops, customized application and feedback forms, typed and voice feedback, as well as storage and export of data within a relational database.

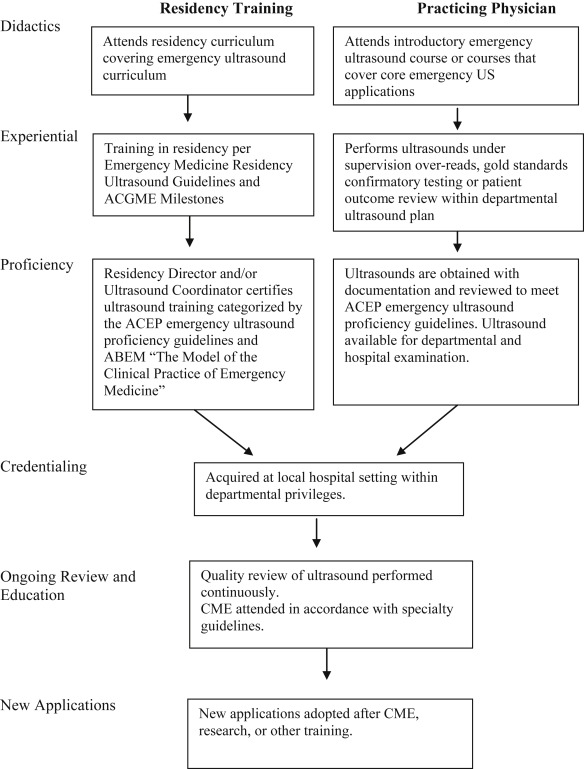

Training Pathways

There are two recommended pathways for clinicians to become proficient in EUS. See Figure 3 . The majority of emergency physicians today receive EUS training as part of an ACGME-approved EM residency. A second practice-based pathway is provided for practicing EM physicians and other EM clinicians who did not receive EUS training through completion of an EM residency program.

These updated EUS guidelines continue to provide the learning objectives, educational methods and assessment measures for either pathway. Learning objectives for each application are described in Appendix 2 .

Residency-Based Pathway

EUS has been considered a fundamental component of emergency medicine training for over two decades. The ACGME mandates procedural competency in EUS for all EM residents as it is a “skill integral to the practice of Emergency Medicine” as defined by the 2013 Model of the Clinical Practice of EM. The ACGME and the American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) recently defined twenty-three sub competency milestones for emergency medicine residency training. Patient Care Milestone twelve (12) describes the sequential learning process for EUS and should be considered a guideline in addition to other assessment methods mentioned in this guideline. Appendix 3 provides recommendations for EM residency EUS education.

Upon completion of residency training, emergency medicine residents should be provided with a standardized EM Resident EUS credentialing letter. For the EUS faculty, ED Director or Chairperson at the graduate’s new institution, this letter provides a detailed description of the EUS training curriculum completed, including the number of quality reviewed training exams completed by application and overall, and performance on SDOTs and simulation assessments.

Practice Based Pathway

For practicing emergency medicine (EM) attendings who completed residency without specific EUS training, a comprehensive course, series of short courses, or preceptorship is recommended. Shorter courses covering single or a combination of applications may provide initial or supplementary training. As part of pre-course preparation, EUS faculty must consider the unique learning needs of the participating trainees. The course curriculum should include trainee-appropriate learning objectives, educational methods and assessment measures as outlined by these guidelines. If not completed previously, then introductory training on US physics and knobology is required prior to training in individual applications. Pre-course and post-course online learning may be utilized to reduce the course time spent on traditional didactics and facilitate later review. Small group hands-on instruction with EUS faculty on models, simulators, and task trainers provides experience in image acquisition, interpretation, and integration of EUS exam findings into patient care. See Appendix 4 .

Preceptorships typically lasting 1-2 weeks at an institution with an active EUS education program have also been utilized successfully to train practicing physicians. Each preceptorship needs to begin with a discussion of the trainees’ unique educational needs, hospital credentialing goals as well as financial support for faculty teaching time. Then the practicing physician participates in an appropriately tailored curriculum typically in parallel with ongoing student, resident, fellow and other educational programming.

Similar to an EM Resident EUS credentialing letter, course and preceptorship certificates should include a description of the specific topics and applications reviewed, total number of training exams completed with expert supervision, performance on other course assessment measures such as SDOTs or simulation cases, as well as the number of CME hours earned. These certificates are then given to local EUS faculty or ED Director/Chairperson to document training.

Advanced Practice Providers, Nursing, Paramedics, and other EM clinicians

In many practice environments, EUS faculty often provide clinical US training to other to non-physician staff including Advanced Practice Professionals, Nurses, Paramedics, Military Medics and Disaster Response Team members. The recommendations in these guidelines should be utilized by EUS faculty when providing such training programs. Pre-course preparation needs to include discussions with staff leadership to define role-specific learning needs and applications to be utilized. Introductory US physics, knobology, and relevant anatomy and pathophysiology are required prior to training in targeted applications.

For Advanced Practice Providers and other clinicians practicing in rural and austere environments where direct EUS trained EM physician oversight is not available, EUS training needs to adhere to the recommendations in these guidelines. Specifically, comprehensive didactics and skills training, as well as minimum benchmarks need to be completed prior to independent EUS utilization. Beyond this initial training, EUS faculty are needed to provide ongoing quality assurance review. Telemedicine may provide the opportunity for real time patient assessment, assistance with image acquisition, and immediate review of patient images.

Ongoing Education

As with all aspects of emergency medicine, ongoing education is required regardless of training pathway. The amount of education needed depends on the number of applications being performed, frequency of utilization, the local practice of the individual clinician and other developments in EUS and EM. Individual EUS credentialed physicians should continue their education with a focus on US activities as part of their overall educational activities. Educational sessions that integrate US into the practice of EM are encouraged, and do not have to be didactic in nature, but may be participatory or online. Recommended EUS educational activities include conference attendance, online educational activities, preceptorships, teaching, research, hands-on training, program administration, quality assurance, image review, in-service examinations, textbook and journal readings, as well as morbidity and mortality conferences inclusive of US cases. US quality improvement is an example of an activity that may be used for completion of the required ABEM Assessment of Practice Performance activities.

Fellowship Training

Fellowships provide the advanced training needed to create future leaders in evolving areas of medicine such as clinical US. This advanced training produces experts in clinical US and is not required for the routine utilization of EUS.

An EUS fellowship provides a unique, focused, and mentored opportunity to develop and apply a deeper comprehension of advanced principles, techniques, applications, and interpretative findings. Knowledge and skills are continually reinforced as the fellow learns to effectively educate new trainees in EUS, as well as clinicians in other specialties, and practice environments. A methodical review of landmark and current literature, as well as participation in ongoing research, creates the ability to critically appraise and ultimately generate the evidence needed for continued improvements in patient care through clinical US. Furthermore, fellowship provides practical experience in EUS program management including quality assurance review, medical legal documentation, image archiving, reimbursement, equipment maintenance, and other administrative duties of an EUS program director.

Recommendations for fellowship content, site qualifications, criteria for fellowship directors, and minimum graduation criteria for fellows have been published by national EUS leadership and ACEP Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship Guidelines. Each fellowship program’s structure and curriculum will vary slightly based on local institution and department resources. At all fellowship programs, mentorship and networking are fundamental to a fellow’s and program’s ultimate success. Both require significant EUS faculty time for regular individual instruction as well as participation in the clinical US community locally and nationally. Hence, institution and department leadership support is essential to ensuring an appropriate number of EUS faculty, each provided with adequate non-clinical time.

For the department, a fellowship speeds the development of an EUS program. Fellowships improve EM resident training resulting in increased performance of EUS examinations. Furthermore, a fellowship training program may have a significant positive impact on overall EUS utilization, timely quality assurance review, faculty credentialing, billing revenue, and compliance with documentation. For an institution, an EUS fellowship provides a valuable resource for other specialties just beginning clinical US programs. Collaborating with EUS faculty and fellows, clinicians from other departments are often able to more rapidly educate staff and create effective clinical US programs.

US in Undergraduate Medical Education

Emergency Medicine has again taken a lead role in efforts to improve Undergraduate Medical Education (UME) through the early integration of clinical US. During the preclinical years, US has been demonstrated to be an effective educational method to reinforce student understanding of anatomy, physical examination skills, pathology and bedside diagnostic skills. During the clinical years, students are then better able to utilize US for clinical diagnosis and on specific rotations. US exposure in UME can provide a solid knowledge base for individuals to build upon and later utilize as US is integrated into their clinical training.

Integrating US into UME

Integration of US into pre-clinical UME often begins with medical student and faculty interest. By working closely with a medical school’s curriculum committee, US may then be incorporated as a novel educational method to enhance learning within existing preclinical courses. Although dedicated US specific curriculum time is not often available in UME, considerable clinical US faculty time and expertise is still required for effective integration of US into existing medical school courses. Widespread clinical US utilization by different specialties within a medical school’s teaching hospitals, and education within Graduate Medical Education programs, provides initial faculty expertise, teaching space, and US equipment. Ongoing education then requires local departmental and medical school leadership support, as well as continued organized collaboration between faculty from participating specialties.

Innovative educational methods again provide the opportunity for clinical US faculty to focus on small group hands-on instruction as described in the innovative education section.

Many academic departments that currently offer clinical rotations within Emergency Medicine already include an introduction to EUS as a workshop, or a set number of EUS shifts. Dedicated EUS elective rotations provide an additional opportunity for medical students interested in Emergency Medicine and other specialties utilizing clinical US to participate in an EUS rotation adapted to their level of training and unique career interests. See Appendix 5 for recommendations for EUS and Clinical US medical school rotations.

US in UME continuing into Clinical US in GME

UME US experience should prepare new physicians to more rapidly utilize clinical US to improve patient care during graduate medical education (GME) training. Medical students today therefore should graduate with a basic understanding of US physics, machine operation, and common exam protocols such as US guided vascular access. Medical students matriculating from a school with an integrated US curriculum, as well as those completing an elective clinical US rotation, should be provided with a supporting letter similar in regards to didactics, hands-on training, and performed examinations. Although all trainees need to complete the EUS residency milestones, trainees with basic proficiency in clinical US from UME training may progress more rapidly and ultimately achieve higher levels of EUS expertise during GME. Additionally, these residents may provide considerable EUS program support as peer-to-peer instructors, residency college leaders, investigators and potentially future fellows.

Section 4 – Credentialing and Privileging

Implementing a transparent, high quality, verifiable and efficient credentialing system is an integral component of an emergency US program. An emergency US director, along with the department leadership, should oversee policies and guidelines pertaining to emergency US. The department should follow the specialty- specific guidelines set forth within this document for their credentialing and privileging process.

Pertaining to clinician performed US, the American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates in 1999 passed a resolution (AMA HR. 802) recommending hospitals’ credentialing committees follow specialty-specific guidelines for hospital credentialing decisions related to US use by clinicians. This resolution affirms that US imaging is within the scope of practice of appropriately trained physician specialists and provides clear support for hospital credentialing committees to grant emergency US (EUS) privileging based on the specialty-specific guidelines contained within this document without the need to seek approval from other departments. Furthermore, HR 802 states that opposition that is clearly based on financial motivation meets criteria to file an ethical complaint to the AMA.

The provision of clinical privileges in EM is governed by the rules and regulations of the department and institution for which privileges are sought. The EM Chairperson or Medical Director or his/her designate (eg, emergency US director) is responsible for the assessment of clinical US privileges of emergency physicians. When a physician applies for appointment or reappointment to the medical staff and for clinical privileges, including renewal, addition, or rescission of privileges, the reappraisal process must include assessment of current competence. The EM leadership will, with the input of department members, determine the means by which each emergency physician will maintain competence and skills and the mechanism by which each physician is monitored.

EM departments should list emergency US within their core emergency medicine privileges as a single separate privilege for “Emergency US” or US applications can be bundled into an “US core” and added directly to the core privileges. EM should take responsibility to designate which core applications it will use, and then track its emergency physicians in each of those core applications. To help integrate physicians of different levels of sonographic competency (graduating residents, practicing physicians, fellows and others), it is recommended that the department of emergency medicine create a credentialing system that gathers data on individual physicians, which is then communicated in an organized fashion at predetermined thresholds with the institution-wide credentialing committee. This system focuses supervision and approval at the department level where education, training, and practice performance is centered prior to institutional final review. As new core applications are adopted, they should be granted by an internal credentialing system within the department of emergency medicine.

Eligible providers to be considered for privileging in emergency ultrasonography include emergency physicians or other providers who complete the necessary training as specified in this document via residency training or practice based training (see Section 3 – Training and Proficiency ). After completing either pathway, these skills should be considered a core privilege with no requirement except consistent utilization. At institutions that have not made EUS a core privilege, submission of 5-10% of the initial requirement for any EUS application is sufficient to demonstrate continued proficiency.

Sonographer certification or emergency US certification by external entities is not an expected, obligatory or encouraged requirement for emergency US credentialing. Physicians with advanced US training or responsibilities may be acknowledged with a separate hospital credential if desired.

Regarding recredentialing or credentialing at a new health institution or system, ACEP recommends that once initial training in residency or by practice pathway is completed, credentialing committees recognize that training as a core privilege, and ask for proof of recent updates or a short period of supervision prior to granting full privileges.

In addition to meeting the requirements for ongoing clinical practice set forth in this document, physicians should also be assessed for competence through the CQI program at their institution. (See Section 5-Quality and US Management ) The Joint Commission (TJC) in 2008 implemented a new standard mandating detailed evaluation of practitioners’ professional performance as part of the process of granting and maintaining practice privileges within a healthcare organization. This standard includes processes including the Ongoing Professional Practice Evaluation (OPPE) and the Focused Professional Practice Evaluation (FPPE). Specific to FPPE and US credentialing, for infrequently performed US examinations, FPPE monitoring can be performed on a pre-determined number of examinations (ie, review of the diagnoses made on the first 10 or 20 of a particular US examination). The FPPE process should: 1. Be clearly defined and documented with specific criteria and a monitoring plan; 2. Be of fixed duration; and 3. Have predetermined measures or conditions for acceptable performance. OPPE can incorporate EUS quality improvement processes. US directors should follow these guidelines when setting up their credentialing and privileging processes.

Section 5 – Quality and US Management

In order to ensure quality, facilitate education, and satisfy credentialing pathways, a plan for an emergency US quality assurance (QA) and improvement program should be in place. This plan should be integrated into the overall ED operations.

The facets of such a program are listed below. Programs should strive for meeting these criteria, and may seek accreditation through the Clinical Ultrasound Accreditation Program (CUAP).

Emergency US Director

The emergency US director is a board-eligible or certified emergency physician who has been given administrative oversight over the emergency US program from the EM Chairperson, director or group. This may be a single or group of physicians, depending on size, locations, and coverage of the group.

Specific responsibilities of an US director and associates may include:

- –

Developing and ensuring compliance to overall program goals: educational, clinical, financial, and academic.

- –

Selecting appropriate US machines for clinical care setting and developing and monitoring maintenance care plan to ensure quality and cleanliness

- –

Designing and managing an appropriate credentialing and privileging program for physicians, residents, or advanced practice providers (APP) or other type of providers within the group and/or academic facility.

- –

Designing and implementing in-house and/or out-sourced educational programs for all providers involved in the credentialing program.

- –

Monitoring and documenting individual physician privileges, educational experiences, and US scans,

- –

Developing, maintaining, and improving an adequate QA process in which physician scans are reviewed for quality in a timely manner and from which feedback is generated.

The emergency US director must be credentialed as an emergency physician and maintain privileges for emergency US applications. If less than two years in the position of US director, it is recommended that the director have either: 1) graduated from an emergency US fellowship, 2) participated in an emergency US management course, or 3) completed an emergency US preceptorship or mini-fellowship. If part of a multihospital group, there must be consideration of local US directors with support from overall system US director. Institutional and departmental support should be provided for the administrative components listed above.

Supervision of US Training and Examinations

Ultrasound programs in clinical specialties have a continuing and exponential educational component encompassing traditionally graduate and post-graduate medical training, but now undergraduate, APP, prehospital, remote, and other trainees are seeking training. Policies regarding the supervision and responsibility of these US examinations should be clear. (See Sections 2, 3 , and 4 )

US Documentation

Emergency US is different from consultative US in other specialties as the emergency physician not only performs but also interprets the US examination. In a typical hospital ED practice, US findings are immediately interpreted, and should be communicated to other physicians and services by written reports in the ED medical record. Emergency US documentation reflects the nature of the exam, which is focused, goal-directed, and performed at the bedside contemporaneously with clinical care. This documentation may be preliminary and brief in a manner reflecting the presence or absence of the relevant findings. Documentation as dictated by regulatory and payor entities may require more extensive reporting including indication, technique, findings, and impression. Although EMRs are quickly becoming the norm, documentation may be handwritten, transcribed, templated, or computerized. Regardless of the documentation system, US reports should be available to providers to ensure timely availability of interpretations for consultant and health care team review. Ideally, EMR systems should utilize effective documentation tools to make reporting efficient and accurate.

During out-of-hospital, remote, disaster, and other scenarios, US findings may be communicated by other methods within the setting constraints. Incidental findings should be communicated to the patient or follow-up provider. Discharge instructions should reflect any specific issues regarding US findings in the context of the ED diagnosis. Hard copy (paper, film, video) or digital US images are typically saved within the ED or hospital archival systems. Digital archival with corresponding documentation is optimal and recommended. Finally, documentation of emergency US procedures should result in appropriate reimbursement for services provided. (See Section 6 – Value and Reimbursement )

Quality Improvement Process

Quality improvement (QI) systems are an essential part of any US program. The objective of the QI process is to evaluate the images for technical competence, the interpretations for clinical accuracy, and to provide feedback to improve physician performance.

Parameters to be evaluated might include image resolution, anatomic definition, and other image quality acquisition aspects such as gain, depth, orientation, and focus. In addition, the QI system should compare the impression from the emergency US interpretation to patient outcome measures such as consultative US, other imaging modalities, surgical procedures, or patient clinical outcome.

The QI system design should strive to provide timely feedback to physicians. Balancing quality of review with provision of timely feedback is a key part of QA process design. Any system design should have a data storage component that enables data and image recall.

A process for patient callback should be in place and may be incorporated into the ED’s process for calling patients back. Callbacks should occur when the initial image interpretation, upon QA review, may have been questionable, inappropriate and of clinical significance. In all cases, the imaging physician is informed of the callback and appropriate counseling/training is provided.

Due to the necessities of credentialing, it is prudent to expect that all images obtained prior to a provider attaining levels sufficient for credentialing should be reviewed.

Once providers are credentialed, programs should strive to sample a significant number of images from each provider that ensures continued competency. Due to the varieties of practice settings, the percentage of scans undergoing quality assurance should be determined by the US director and should strive to protect patient safety and maintain competency. While this number can vary, a goal of 10% may be reasonable, adjusted for the experience of the providers and newness of the US application in that department.

The general data flow in the QA system is as follows:

- 1.

Images obtained by the imaging provider should be archived, ideally on a digital system. These images may be still images or video clips, and should be representative of the US findings.

- 2.

Clinical indications and US interpretations are documented on an electronic or paper record by the imaging provider.

- 3.

These images and data are then reviewed by the US director or his/her designee.

- 4.

Reviewers evaluate images for accuracy and technical quality and submit the reviews back to the imaging provider.

- 5.

Emergency US studies are archived and available for future review should they be needed.

QA systems currently in place range from thermal images and log books to complete digital solutions. Finding the system that works best for each institution will depend on multiple factors, such as machine type, administrative and financial support, and physician compliance. Current digital management systems offer significant advantages to QA workflow and are recommended.

US QA may also contribute to the ED’s local and national QI processes. US QA activities may be included in professional practice evaluation, practice performance, and other quality improvement activities. Measures such as performance of a FAST exam in high acuity trauma, detection of pregnancy location, use of US for internal jugular vein central line cannulation may be the initial logical elements to an overall quality plan. In addition, US QA databases may contribute to a registry regarding patient care and clinical outcomes.

US programs that include multiple educational levels and various types of providers should implement processes to integrate QA into the education process as well as the departmental or institutional quality framework. Technology allowing remote guidance and review may be integrated into the US QA system.

US Machines, Safety, and Maintenance

Dedicated US machines located in the ED for use at all times by emergency physicians are essential. Machines should be chosen to handle the rigors of the multi-user, multi-location practice environment of the ED. Other issues that should be addressed regarding emergency US equipment include: regular in-service of personnel using the equipment and appropriate transducer care, stocking and storage of supplies, adequate cleaning of external and internal transducers with respect to infection control, maintenance of US machines by clinical engineering or a designated maintenance team, and efficient communication of equipment issues. Ultrasound providers should follow common.

ED US safety practices including ALARA, probe decontamination, and machine maintenance.

Risk Management

US can be an excellent risk reduction tool through 1) increasing diagnostic certainty, 2) shortening time to definitive therapy, and 3) decreasing complications from procedures that carry an inherent risk for complications. An important step to managing risk is ensuring that physicians are properly trained and credentialed according to national guidelines such as those set by ACEP. Proper quality assurance and improvement programs should be in place to identify and correct substandard practice. The greatest risk in regards to emergency US is lack of its use in appropriate cases.

The standard of care for emergency US is the performance and interpretation of US by a credentialed emergency physician within the limits of the clinical scenario. Physicians performing US imaging in other specialties or in different settings have different goals, and documentation requirements, and consequently should not be compared to emergency US. As emergency US is a standard emergency medicine procedure, it is included in any definition of the practice of emergency medicine with regards to insurance and risk management.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree