INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

During 2002–2005, 15,600 people under 20 years of age were newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes annually in the United States.1 Classification of diabetes (American Diabetes Association) is shown in Table 223-1.2,3

|

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Type 1 diabetes is characterized by almost no circulating insulin and the failure of β-cells to respond to insulinogenic stimuli. This accounts for only 5% to 10% of all cases of diabetes and is mostly diagnosed in children and young adults, with peaks before school age and at puberty. Immune-mediated destruction of β-cells causes 90% of these cases, and the remainder have no known cause. Spontaneous ketoacidosis almost always develops in untreated cases, and insulin is required for survival. It is often not possible to clearly classify patients as type 1 or type 2 in the ED.3

Chapter 224, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, discusses type 2 diabetes mellitus in detail. Hyperglycemia is present in all types of diabetes mellitus and is the main factor responsible for complications. Therefore, maintaining euglycemic control is the cornerstone of management.

DIAGNOSIS

The American Diabetes Association criteria for diagnosis are listed in Table 223-2.2,3 Any one of these can be used to make the diagnosis. Patients with a fasting plasma glucose of 100 milligrams/dL to 125 milligrams/dL (5.6-7.0 mmol/L), a hemoglobin A1C of 5.7% to 6.4%, or a 2-hour plasma glucose of 140 to 199 milligrams/dL (7.8-11.0 mmol/L) as part of an oral glucose tolerance test are classified as having prediabetes.2

| A1C ≥6.5%* | The test should be performed in a laboratory using a method that is NGSP certified and standardized to the DCCT assay. |

Or Fasting plasma glucose ≥126 milligrams/dL (7.0 mmol/L)* | Fasting is defined as no caloric intake for at least 8 h. |

Or Casual plasma glucose ≥200 milligrams/dL (11.1 mmol/L) and symptoms of hyperglycemia | Classic symptoms of hyperglycemia include polyuria, polydipsia, and unexplained weight loss. |

Or 2-h plasma glucose ≥200 milligrams/dL (11.1 mmol/L) during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)* | OGTT must be performed as described by the World Health Organization. |

Glycated hemoglobin represents the average blood glucose level over the period of red blood cell half-life. The glycated hemoglobin assay may not be accurate for diagnosis of diabetes in patients with increased red blood cell turnover such as thalassemia, anemia, chronic kidney or liver disease, pregnancy, or in patients who have had heavy bleeding or received a transfusion within the preceding 3 months.2

In the ED, it is common to encounter isolated elevations of blood glucose with no established relationship to a meal (“casual plasma glucose,” as defined by the American Diabetes Association). Ask about symptoms of hyperglycemia and refer to a primary care physician.

TREATMENT

Type 1 diabetes is characterized by an absolute insulin deficiency, so some form of insulin is required for survival. In addition to insulin, patients with type 1 diabetes may also be treated with prandial injections of pramlintide, a synthetic form of the β-cell–produced hormone amylin, which aids in suppressing glucagon secretion.4 Patients with type 1 diabetes may also benefit from β-cell transplantation, pancreas transplantation, or combined kidney/pancreas transplantation. Other noninsulin agents are useful in type 2 diabetes and are discussed separately in chapter 224.

Currently, all insulin sold in the United States is of human type and manufactured using recombinant DNA technology (bovine or porcine insulin can still be obtained via special permission from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration). Modern insulin is highly pure and stable, and vials in use can be kept up to 30 days at room temperature. All types of insulin are standardized to a concentration of 100 units/mL (“U100”). When extremely high doses of insulin are required, a concentration of 500 units/mL (“U500”) of regular insulin can also be used in consultation with an endocrinologist.

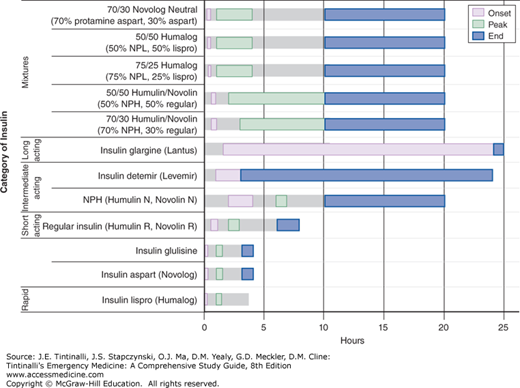

Although unmodified “regular” insulin was the first type of insulin used, many new insulin analogues have now become available (Table 223-3, Figure 223-1).5,6 There can be considerable variability in the onset and duration of action depending on the dose (e.g., regular insulin has a longer duration of action with larger doses), site of injection, degree of exercise, and presence of circulating anti-insulin antibodies. Use of insulin analogues and highly pure insulin preparations has reduced the emergence of anti-insulin antibodies.

| Category of Insulin or Analogue | Name | Pharmacokinetics | Unique Properties | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset (hour) | Peak (hour) | End (hour) | |||

| Rapid acting | Insulin lispro (Humalog®) Insulin aspart (NovoLog®) Insulin glulisine (Apidra®) | 0.1–0.25 0.1–0.25 0.1–0.25 | 1.0–1.5 1–2 1.0–1.5 | 4 4–6 3–4 | Fixed duration of action, regardless of dose Useful in patients allergic to insulin and other analogues13,14,15 More stable than other rapid-acting insulins Antiapoptotic; may counteract β-cell destruction16 |

| Short acting | Regular insulin (Humulin R®, Novolin R®) | 0.25–1.0 | 2–4 | 6–8 | — |

| Intermediate acting | NPH (Humulin N®, Novolin N®) Insulin detemir (Levemir®) | 2–4 1–3 | 6–7 9–? | 10–20 6–24 | Inexpensive Action is relatively constant with gentle peak |

| Long acting | Insulin glargine (Lantus®) | 1.5 | No peak | 24+ | Cannot be mixed with other insulins in same syringe |

| Mixtures | 70/30 Humulin®/Novolin® (70% NPH, 30% regular) 50/50 Humulin®/Novolin® (50% NPH, 50% regular) 75/25 Humalog® (75% NPL, 25% lispro) 50/50 Humalog® (50% NPL, 50% lispro) 70/30 NovoLog Neutral® (70% protamine aspart, 30% aspart) | 0.5–1.0 0.5–1.0 0.2–0.5 0.2–0.5 0.2–0.5 | 3–12 2–12 1–4 1–4 1–4 | 10–20 10–20 10–20 10–20 10–20 | — — — — — |

A physiologic regime of insulin generally starts with half of the daily requirement given as basal insulin (once-daily long-acting, or twice-daily intermediate-acting insulin) and a prandial dose of rapid-acting insulin administered 5 to 30 minutes before a meal.5 Prandial dosing is most often based on the amount of carbohydrate that is about to be consumed, for example, 1 unit of insulin for each 15 grams of carbohydrate; this is known as “carb counting.” Alternatively, some patients may be on a simplified, fixed amount of insulin for each meal.

Insulin can be given as intermittent dosing, IV infusion, or continuous subcutaneous infusion using an insulin pump.

Intermittent insulin doses are given with a syringe or pen. The syringe method is the least expensive, but requires care and precision to give the correct dose. Pens provide more accurate dosing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree