TRIAGE

DEBRA A. POTTS, MSN, RN, CPEN, CEN AND MARY KATE FUNARI, MSN, RN, CPEN

INTRODUCTION

Children are cared for in all emergency departments (EDs) from general EDs that see primarily adult patients to those general EDs with a separate pediatric section to pediatric EDs that exist within a pediatric institution. In the last two decades there has been a considerable increase in ED visits in the United States, a fourth of these visits by children. In 2010, there were 25.5-million ED visits for children less than 18 years of age. As the health burden on emergency services continues to rise it is critical to have a reliable method of triaging children presenting for services.

HISTORY OF TRIAGE

The term “triage” derived from the French word “trier,” to sort, was first used back in the 18th century to document the severity of injury in warfare. Battlefield triage eventually made its way into the American medical system and in 1964 Wasserman et al. published the first use of civilian triage in EDs. Subsequently many institutions, federal agencies, and emergency medical systems have continued to study and refine triage systems in the United States.

CURRENT TRIAGE SYSTEMS

Pediatric triage requires rapid assessment of those presenting to the ED including determination of severity of illness or injury, assignment of acuity level, and anticipation of appropriate emergency care resources needed. With limited resources available, the goal of the triage process is “right patient, right provider, right care, right time,” which demands a standardized approach. The American College of Emergency Physicians and the Emergency Nurses Association have recommended that EDs use a reliable and valid five-level triage system for prioritizing the care of children presenting to the ED. In 2010, the ACEP and ENA based on expert consensus of currently available evidence supported the adoption of a reliable, valid five-level triage system such as the Emergency Severity Index (ESI). Following the release of this position statement, the number of EDs using the five-level ESI triage system increased significantly.

Comprehensive triage has been the dominant model for assigning triage acuity in US EDs. Triage acuity systems have been based on the nurse’s assessment of vital signs and physical examination along with subjective information including past medical history, medications, allergies, and history of the presenting complaint. These systems require the nurse to assign an acuity level by determining how acutely ill the patient is and how long they can wait to be seen by a provider.

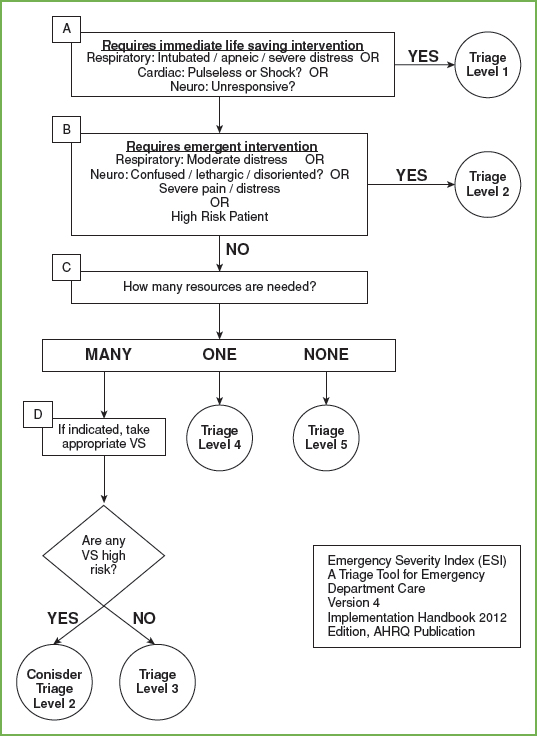

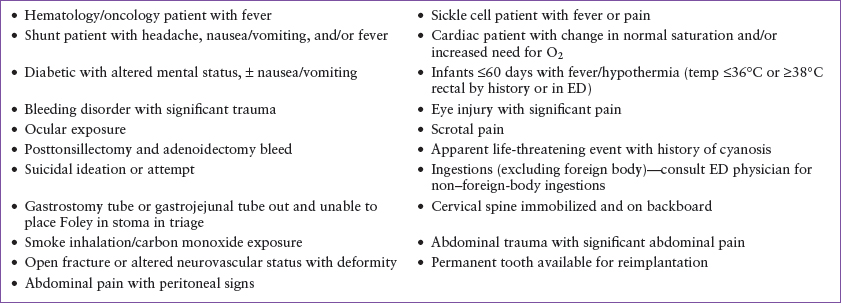

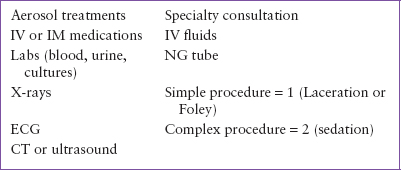

The ESI is a five-level triage system developed by a group of emergency physicians and nurses in the late 1990s. The ESI is distinctive in its method of triage as it integrates both acuity and resource utilization. This system relies on nursing judgment for the more acutely ill patients (ESI levels 1 and 2), while asking nurses to assign lesser acuities (ESI levels 3 to 5) to the less acutely ill by predicting the number of resources such as diagnostic tests and procedures each patient will need in determining disposition. Triage nurses follow an algorithm for determining acuity (Fig. 73.1). The nurse answers specific questions for determining the more acutely ill at points A and B. Point B takes into consideration special high-risk conditions in pediatrics (Table 73.1). If the child is determined to be less acute, direction is given to what constitutes a resource and nurses are only required to estimate up to two resources (Table 73.2). Multiple studies of general ED populations have validated the ESI triage system with good interrater reliability and the ability to estimate ED resources when triage was performed by experienced and trained ED nurses.

The ESI has continually been validated and improved upon through research. ESI version 4 (2012 edition) was born out of the Pediatric ESI Research Consortium’s large, multicenter study on pediatric triage and a comprehensive review of pediatric emergency courses and textbooks. Improvements to ESI included a designated chapter on pediatric triage and more pediatric triage case scenarios for educational use.

In 2009 the American Hospital Association reported that 57% of US hospitals were using the ESI triage system. Standardization of triage systems across the United States will allow for increased sharing of ED data and setting performance metrics for care. Establishing a standard for triage acuity assessment will further facilitate benchmarking, public health surveillance, and research.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics reports national level data on ED visits. The report categorizes patients in five levels on how urgently they need to be seen by a provider and includes immediate (immediately), emergent (1 to 14 minutes), urgent (15 to 60 minutes), semi-urgent (1 to 2 hours), nonurgent (2 to 24 hours). While there is no research to support this classification it allows for sharing of national level data on acuity mix when patients present to the ED.

PEDIATRIC TRIAGE CONSIDERATIONS

The triage nurse needs a solid foundation of knowledge related to specific anatomic and physiologic issues that may put a child at risk, as well as age-dependent “red flags” that must be considered during triage. The nurse should also be comfortable interacting with children of all ages. The following are key points when assessing a child:

FIGURE 73.1 ESI triage algorithm.

TABLE 73.1

HIGH-RISK PATIENTS

TABLE 73.2

TRIAGE RESOURCES

1. Children have a larger body surface area than adults. This places them at risk for both heat and fluid loss.

2. Neonates have poor thermoregulation. They should not be undressed for any extended length of time as this cold stress causes increased metabolic demands resulting in potential physiologic decompensation.

3. Critically ill neonates/children can present with subtle signs such as hypothermia, poor feeding, and irritability.

4. Cardiac output is heart rate dependent in neonates and young children. Bradycardia or severe tachycardia can be very dangerous. Hypotension is a late finding.

5. Weight in kilograms is important in order to safely administer medications to children. Estimation of weights in critically ill children should be done with validated tools and estimated guesses by providers and caregivers are discouraged.

6. Children are portable. The most critically ill child may arrive being carried into your ED, you must be ready.

7. Caregivers’ perception of illness is key. Providers must listen as caregivers know their children best and can explain when behavior is abnormal.

8. Triage nurses must be aware of risk factors for abuse. Anything that stresses a family puts children at risk such as lower socioeconomic levels, history of substance abuse, history of mental illness, and single caregiver households. Young children as well as children with chronic illness or disabilities are at increased risk. The nurse’s knowledge of child development is very important when assessing injuries. The nurse needs to assess if the injuries can be explained knowing the current developmental level of the child.

Triage Process

As previously described, triage is fundamental in determining the severity of illness and immediate needs of a patient who presents to the ED. The pediatric triage process consists of a rapid initial assessment, primary survey, secondary survey, and triage decision. Ideally, triage should take no more than 3 to 5 minutes. Documentation of triage findings and interventions as well as reassessment of patients in the waiting room is also included in triage workflow. Care of pediatric patients requires a core understanding of developmental stages and their associated risk factors, injury and illness patterns, and physiologic compensatory mechanisms. As such, the triage process should be completed only by ED nurses experienced in pediatric patients who demonstrate sound assessment, clinical judgment, and decision-making skills. Should the triage provider’s assessment indicate the need for immediate lifesaving intervention, the triage process should end and the patient moved to a treatment area for care and further assessment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree