Chapter 7 Triage

The National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, Emergency Department Summary, estimated that 123.8 million visits were made to U.S. emergency departments in 2008.1

Environment

In today’s busy ED, the triage function has become even more critical. The number of persons seeking medical care in EDs grew by 32% between 1996 and 2006.2 This number is expected to continue to grow in light of the aging population, the number of uninsured patients, and issues surrounding access to primary care. In fact, in 2005, 20% of the United States population had made one or more visits to an ED within the past year.2 In 2002 The Joint Commission3 released a sentinel event alert that identified EDs as the location for more than half of all reported sentinel events involving patient death or permanent disability because of delays in treatment. In nearly one third of these occurrences, overcrowding was deemed to be a contributing factor. Given this environment, an effective triage process is crucial to the smooth functioning of an ED.

Triage Systems

Comprehensive

Comprehensive triage is the most advanced system and is the process currently recommended by the Emergency Nurses Association’s (ENA) Standards of Emergency Nursing Practice, which defines the practice as follows: “The [emergency nurse] triages each patient and determines the priority of care based on physical, developmental, and psychosocial needs as well as factors influencing access to health care and patient flow through the emergency care system.”4 The backbone of this approach is the experienced emergency nurse who has completed a competency-based triage orientation process. Advantages of comprehensive triage are highlighted in Table 7-1.

TABLE 7-1 ADVANTAGES OF COMPREHENSIVE TRIAGE

Two-Tiered Triage Systems

• A patient with a serious complaint is immediately identified.

• The first triage nurse will know every patient in the waiting room and can keep an eye on them.

• The first triage nurse can answer any questions, address changes in patient status, and perform reassessments as appropriate.

• The detailed assessment performed by the second triage nurse builds on the rapid initial assessment. If the patient omitted vital information, the triage decision can always be changed.

Triage Severity Rating Systems

Studies have demonstrated poor inter-rater (between different raters) and intra-rater (the same rater on another occasion) reliability with three-level triage severity rating systems.5–7 This is largely because there are no universal definitions for each level. Table 7-2 defines two-, three-, and four-level triage systems and the definitions for each triage level.

TABLE 7-2 OVERVIEW OF TWO-, THREE-, AND FOUR-LEVEL TRIAGE ACUITY RATING SYSTEMS

Five-Level Triage

ACEP and ENA believe that quality of patient care would benefit from implementing a standardized ED triage scale and acuity categorization process. Based on expert consensus of currently available evidence, ACEP and ENA support the adoption of a reliable, valid 5-level triage scale.8

In 2004 the Joint Five-Level Triage Task Force identified the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) or the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) as good options based on a review of the published evidence on five-level triage systems.9

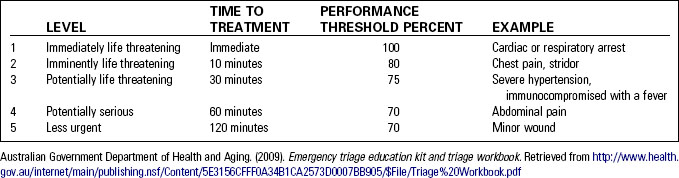

The Australasian Triage Scale

The Australian emergency medical community adopted the Australasian Triage Scale in 1993, and it remains in use in every ED in Australia (Table 7-3). Based on research and expert consensus, each category lists clinical descriptors or conditions that correspond to a specific severity level. Objective time frames for physician evaluation are set for each classification. This “time to treatment” is the maximum interval a patient should expect to wait for further assessment and medical intervention. The clock starts when a patient first presents to the ED. The triage nurse selects an Australasian Triage Scale category based on his or her response to the statement: “This patient should wait for medical assessment and treatment no longer than . . .”10 Vital signs are obtained only if they will assist in making the triage severity decision. Performance thresholds are set for each level and indicate what percent of the time the ED must comply with time-to-treatment goals. Research has shown the Australasian Triage Scale to be valid and reliable.11,12 In addition to assigning individual patient severity of condition, this scale has been used to examine case mix and to relate triage levels directly to common outcome measures such as ED length of stay, intensive care unit admission, and resource consumption. Educational materials are available online.13

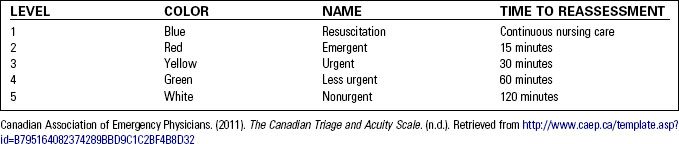

The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale

A group of Canadian emergency physicians developed the five-level CTAS based on the Australasian system14 (Table 7-4). Working with the National Emergency Nurses Affiliation, the tool was adopted as the countrywide standard and has become part of the ED data regularly reported to the Canadian government. The CTAS continues to be updated based on the consensus of the National Working Group, research, and EDs’ experience working with the scale.15 In 2003 the Canadian Emergency Department Information Systems (CEDIS) published a standardized presenting complaint list.16 The CTAS adult and pediatric guidelines have incorporated the CEDIS complaint list as well as the concept of first-order and second-order modifiers.16 The patient’s chief complaint is determined by the triage nurse. This automatically generates a complaint-specific minimum CTAS level, but this level can be altered by the use of objective first- and second-order modifiers. Based on the chief complaint the triage nurse then evaluates first-order modifiers, which are defined as modifiers that are broadly applicable to many different chief complaints. First-order modifiers include vital signs, level of consciousness, pain level, and mechanism of injury. Then second-order modifiers specific to the chief complaint are assessed. The CTAS level assigned is based on the highest level identified by any of the modifiers. Studies have indicated that the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale is valid and reliable.17,18 Standardized educational materials are available online.13

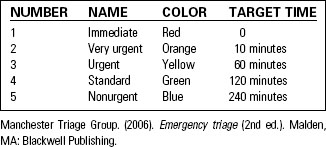

The Manchester Triage Scale

The Manchester triage scale was developed in England by a group of emergency nurses and physicians who created a detailed, flowchart-based system. Each triage level is given a name, number, and color code that identifies the target time frame for a patient to see a treating clinician19 (Table 7-5). Based on the presenting complaint, the triage nurse chooses from 52 different flowcharts. To arrive at a triage level decision, the nurse follows the flowchart, asking about signs and symptoms (or discriminators). A positive answer to a discriminator determines the severity rating. Documentation consists of simply identifying the presentational flowchart used, which discriminator defined the triage score, and the associated triage level. The Manchester triage scale is used throughout the United Kingdom and updated training materials have been published.18

The Emergency Severity Index

Two American emergency physicians working with a team of emergency physicians and nurses created the Emergency Severity Index (ESI).20 This research-based, five-level scale categorizes patients by severity and expected resource needs (Fig. 7-1). Severity is defined as the stability of vital functions and the potential for life, limb, or organ threat. Resource consumption, a component unique to the ESI, is defined as the number of different resources a patient is expected to consume to reach a disposition. The experienced emergency nurse is capable of estimating resource consumption based on previous, similar patient encounters.

Like other five-level systems, research has demonstrated that the ESI is valid and reliable.20–24 The system itself consists of an easy-to-use algorithm designed to rapidly sort patients into one of five mutually exclusive categories. Educational materials include an online course, a training DVD, and a handbook.25,26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree