Triage

Julio R. Lairet

John G. McManus Jr.

OBJECTIVES

After reading this section, the reader will be able to:

Describe the history of triage.

Discuss the importance of using certain physiologic criteria to determine triage categories.

Provide several examples of current triage systems.

Discuss triage principles that are unique to the tactical environment.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Triage as we know it today has evolved from our many experiences throughout the years. Its origin is from the French word trier, which means to sort. During the Napoleonic era, Larrey was the first to establish a system in which soldiers requiring immediate care were attended to initially regardless of rank (1). He was also the first to initiate care of casualties while they were still on the battlefield prior to evacuating them to field hospitals (1).

World War I brought an important advancement in how casualties were managed. For the first time, patients were triaged at central casualty collection points after which they would be moved to receiving facilities. During World War II, a tiered approach to triage was implemented; casualties were treated in the field by medics after which they were directed to higher echelons of care. The implementation of this philosophy was responsible for saving more lives than any other advancement to date (1).

During the last two decades, the question of how we perform triage has re-emerged and taken its place on center stage. This new interest in triage has introduced many new systems designed to sort through patients in an attempt to identify which casualties need medical attention first.

TRIAGE PHILOSOPHY

Triage is defined as a process for sorting injured people into groups based on their need for or likely benefit from immediate medical treatment. It is an ongoing, “dynamic” method by which management of casualties is prioritized for treatment and evacuation. This is by definition a resource-constrained environment. The performance of accurate triage provides tactical emergency medical support (TEMS) with the best opportunity to do the greatest good for the greatest number of casualties. Triage of casualties merely establishes order of treatment, not which treatment is provided. However, during triage, TEMS providers should concentrate on performing necessary lifesaving interventions (LSIs), which could result in a new triage category of that patient. The provider must move quickly to the next patient and not spend large amounts of time with any one patient. LSIs during triage usually include:

▪ Opening the airway through positioning (no advanced airway devices should be used)

▪ Controlling major bleeding through the use of tourniquets or direct pressure provided by other patients or other devices

▪ Relieving a tension pneumothorax with needle decompression

In most situations, the number of victims during a tactical environment will not equal those of a mass casualty incident (MCI) or a disaster. Although resources may be limited, it is important to understand and be prepared to implement the principles of MCI and disaster triage if needed.

MCI triage is carried out across the United States on a regular basis by prehospital providers. During an MCI, the emergency care system becomes stressed, but is not overwhelmed. An MCI cannot be defined by an actual number of casualties, because the rate limiting step will be the capacity of the system and not the number of victims. In

some systems, due to their limited resources, four victims could constitute an MCI, whereas in other systems it could take as many as 10 to 15 victims before the system became stressed. During an MCI, additional personnel can be quickly mobilized to support the operation and, therefore, maintain the appropriate number of resources for the number of casualties. The priority of MCI triage is to identify and care for the sickest casualties first.

some systems, due to their limited resources, four victims could constitute an MCI, whereas in other systems it could take as many as 10 to 15 victims before the system became stressed. During an MCI, additional personnel can be quickly mobilized to support the operation and, therefore, maintain the appropriate number of resources for the number of casualties. The priority of MCI triage is to identify and care for the sickest casualties first.

During a disaster, the system becomes overwhelmed and the available personnel cannot support the number of victims. Because of the limited resources, a divergence occurs in the philosophy of triage. The priority is redirected from caring for the sickest victims to doing the most good for the greater number of patients. This is a difficult transition for most health care providers, because it is human nature to attempt to care for the sickest casualties. The initial objective of triage during a disaster is to identify the victims whose injuries can wait for care without risk (green or minimal) and establish which victims will most likely not survive even if care is rendered (black or expectant). After these two groups are identified, resources can be allocated to sort and care for the remaining casualties who will include those with serious (yellow or delayed) and critical (red or immediate) injuries.

When discussing triage, it is important to address two terms which are integral to performing triage: undertriage and overtriage. Undertriage refers to triage sensitivity in the identification of patients needing LSIs. The goal is to minimize the rate of undertriage, because a high rate will directly impact the mortality and morbidity of those casualties that are triaged to a lower category erroneously. Because it is impossible to achieve a 0% of undertriage, acceptable rates have been established as 5% or less (2).

Overtriage refers to the misclassification of a casualty into a higher category than they actually are. High rates of overtriage can also be problematic, because the system could be overwhelmed by casualties resulting in an increase in morbidity and mortality of critically injured patients (3). Rates of overtriage of up to 50% have been deemed acceptable in an effort to minimize the rates of undertriage (4).

TRIAGE SYSTEMS

Currently, there are several triage tools which are used in the prehospital setting to sort through casualties in MCIs and disasters. The most widely used system is simple triage and rapid treatment (START). This system was developed in 1983 by the Newport Beach Fire Department and Hoag Hospital in California; in 1994, the system was revised (5, 6). The goal of START triage is to identify injuries that could lead to death within 1 hour. This system focuses on respiratory status, perfusion, and the mental status of the casualty. It is important to understand the limitations of the START system as it was designed for conventional trauma and has recently been criticized as ineffective when used at the World Trade Center site on 9/11/01 (7).

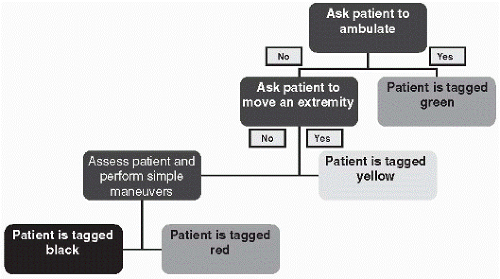

In recent years, move, assess, sort, and send (MASS) triage has emerged as an alternative system for sorting casualties in the pre-hospital environment. This system was introduced by Drs. Coule and Schwartz as part of the National Disaster Life Support Programs (NDLS) (8). It utilizes a rapid grouping system based on the ability to walk and follow commands and assigning the standardized military triage categories based on clinician judgment as its foundation (immediate, delayed, minimal, expectant) (8). It is also a very user-friendly system, which will allow for rapid triage of multiple patients during a MCI or disaster with minimal training of law enforcement and first responders (Fig. 13.1).

The first phase of MASS triage is the “move” phase. All patients who are ambulatory are asked to relocate to a pre-determined location where they will be classified as minimal until they are individually assessed (8). The remaining

patients are asked to follow a simple command, such as moving an arm or a leg. To follow this command, the victims must have sufficient perfusion of the brain to remain conscious, they are initially classified as delayed (8). The remaining group of patients includes both the immediate and expectant group (8).

patients are asked to follow a simple command, such as moving an arm or a leg. To follow this command, the victims must have sufficient perfusion of the brain to remain conscious, they are initially classified as delayed (8). The remaining group of patients includes both the immediate and expectant group (8).

The second step of MASS triage is the “assess” phase; during this phase, the victims that are not moving are evaluated and immediate LSIs are administered (8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree