Military Tactical Operations

Andre M. Pennardt

OBJECTIVES

After reading this section, the reader will be able to:

Describe tactical movement techniques for small and large elements.

Discuss the differences between civilian and military tactical movements.

Describe movement techniques while “under fire.”

Discuss offensive and defensive postures.

TACTICAL MOVEMENT

Compared to civilian tactical team movement, military tactical movement may frequently involve greater distances, greater variation in the type of terrain traveled, and larger numbers of personnel. In addition, whereas civilian tactical movements typically are conducted in proximity to a known hostile force, military tactical movements may include travel in areas where enemy contact is not expected. Fire teams and squads are rough military equivalents for small civilian tactical teams; platoons and companies are progressively larger groups. Combat casualty care is generally provided by medics at platoon and company levels, whereas self- or buddy aid, combat lifesavers, or other first responders are the means of initial treatment at team and squad levels. Casualties are transported from small elements to collection points established by larger units (e.g., platoon or company) when mission requirements permit to facilitate casualty stabilization and monitoring by medics and preparation for evacuation. Compared to civilian operations, the time to definitive treatment and evacuation during military operations is usually longer due to the latter’s focus on mission completion as the highest priority and greater distances involved.

In order to achieve protection from hostile fire when moving, routes are selected that place cover between soldiers and the areas where the enemy is known or suspected to be. The use of terrain features, such as ravines, gullies, hills, wooded areas, and walls, reduces the risk of the enemy seeing the troops and directing effective fire against them. Open areas and hilltops or ridges, which may silhouette soldiers against the sky, must be avoided whenever possible. During movement soldiers must be able to see their fire team leader. The squad leader must be able to see his fire team leaders. The platoon leader should be able to see his lead fire team leader.

INDIVIDUAL MOVEMENT UNDER FIRE

Individual soldiers typically use one of three movement techniques when receiving enemy fire or while under enemy observation: the low crawl, the high crawl, and the rush. The low crawl provides the lowest silhouette and is used to cross terrain where the concealment is very low and enemy fire or observation prevents the soldier from getting up. It is the slowest of the three individual movement techniques. The body is kept flat against the ground during the low crawl. The weapon is grasped at the upper sling-swivel with the firing hand, while the front hand guard rests on the forearm keeping the muzzle off the ground and the weapon butt drags on the ground. In order to move, the arms are pushed forward and the firing side leg is pulled forward. The soldier then pulls himself forward with his arms while pushing with the other leg. This sequence is repeated until the danger area is completely crossed.

The high crawl permits faster movement than the low crawl while still providing a low silhouette. This technique is used when there is good concealment, but enemy fire or observation prevents the soldier from getting up. The body is kept off the ground and rests on the forearms and lower legs. The weapon is cradled in the arms keeping the muzzle off the ground. The knees are kept well behind the buttocks to ensure that the body stays low. The soldier alternately advances his right elbow and left knee, followed by the left elbow and right knee, in order to move forward.

The rush is the fastest way to move from one position to another and should last from 3 to 5 seconds. While the

rushes must be kept short to keep enemy personnel from tracking the soldier, he must not stop and hit the ground in the open simply because 5 seconds have elapsed. The goal of each rush is to move to the next covered and concealed position via the best route. The soldier slowly raises his head and picks the next position and route and then slowly lowers his head again. He draws the arms into the body keeping the elbows in, pulls his right leg forward, raises the body by straightening the arms, and then gets up quickly and runs to the next position. At the conclusion of the rush the soldier plants both his feet, drops to his knees while at the same time sliding a hand to the weapon butt, drops forward breaking the fall with the butt, and goes to a prone firing position. If a soldier has been firing from one position for some time, the enemy may have spotted him and may be awaiting his coming up from behind cover. By rolling or crawling a short distance from his position before beginning a rush, the soldier may be able to fool an enemy who is aiming at the original location and waiting for him to rise.

rushes must be kept short to keep enemy personnel from tracking the soldier, he must not stop and hit the ground in the open simply because 5 seconds have elapsed. The goal of each rush is to move to the next covered and concealed position via the best route. The soldier slowly raises his head and picks the next position and route and then slowly lowers his head again. He draws the arms into the body keeping the elbows in, pulls his right leg forward, raises the body by straightening the arms, and then gets up quickly and runs to the next position. At the conclusion of the rush the soldier plants both his feet, drops to his knees while at the same time sliding a hand to the weapon butt, drops forward breaking the fall with the butt, and goes to a prone firing position. If a soldier has been firing from one position for some time, the enemy may have spotted him and may be awaiting his coming up from behind cover. By rolling or crawling a short distance from his position before beginning a rush, the soldier may be able to fool an enemy who is aiming at the original location and waiting for him to rise.

SMALL TEAM MOVEMENT

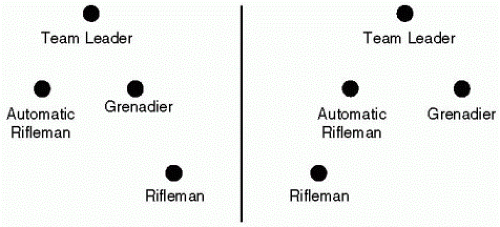

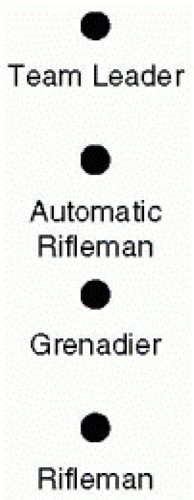

Fire teams use the wedge as the basic formation when moving (Fig. 2.1). The wedge provides easy control of team members, good flexibility and security, and allows immediate fires in all directions. Although the interval between soldiers in the wedge formation is normally 10 meters, the wedge can expand or contract depending on terrain, visibility, and other factors. When rough terrain or poor visibility make control of the wedge difficult, the normal interval is reduced so that all team members can still see their leader and team leaders can still see their squad leader. As control becomes easier, the wedge expands again to improve security. Severely restrictive terrain results in contraction of the edges of the wedge to the point of forming the single file formation (Fig. 2.2). The file provides easier control than the wedge, but is less flexible and secure. Although the file allows immediate fires to the flanks, it masks most fires to the rear.

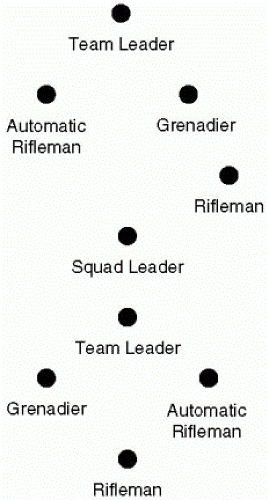

Squads utilize three standard formations for movement: column, line, and file. The squad column is the most common squad formation (Fig. 2.3). The column provides good dispersion laterally and in depth, while simultaneously maintaining control and maneuver capability. The lead fire team is the base fire team allowing the trail fire team to act as a maneuver element to flank the enemy upon contact. The rifleman in the trail fire team provides rear security when the squad moves independently or as the rear element of a platoon.

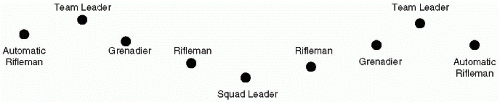

The squad line is designed to provide maximum firepower to the front (Fig. 2.4). This formation provides limited maneuver capability, because both fire teams are committed. It is more difficult to control than the column and provides little security to the flanks and rear. The characteristics of the squad file are the same as that of fire team file, except for the difference in size. The squad file is similarly

used when restrictive terrain prevents a more dispersed or expanded formation. Control can be increased by placing the squad leader at the front of the squad file and a team leader at the rear of the formation.

used when restrictive terrain prevents a more dispersed or expanded formation. Control can be increased by placing the squad leader at the front of the squad file and a team leader at the rear of the formation.

There are three movement techniques that may be used by squads: traveling, traveling overwatch, and bounding overwatch. Leaders decide which technique to use based on the likelihood of enemy contact and the need for speed. Movement techniques are not fixed formations, but rather refer to the distances between soldiers, teams, and squads that vary based on mission, enemy, terrain, visibility, and any other factors affecting control. Each technique is associated with different ease of control, personnel dispersion, speed of movement, and relative security, and can be used with any formation.

Traveling is utilized when enemy contact is not likely. It offers the greatest speed, but the least security, especially forward. During traveling the distance between

individual soldiers would typically be 10 meters and 20 meters between fire teams. Traveling overwatch is the basic squad movement technique and used when enemy contact is possible. It provides less control and slower speed, but more security, than traveling. Distances between individual soldiers increase to approximately 20 meters and 50 meters between fire teams. The lead fire team is far enough ahead to detect or engage the enemy before the opposing force can engage the remainder of the squad, but close enough to still be supported with small arms fire from the trail fire team.

individual soldiers would typically be 10 meters and 20 meters between fire teams. Traveling overwatch is the basic squad movement technique and used when enemy contact is possible. It provides less control and slower speed, but more security, than traveling. Distances between individual soldiers increase to approximately 20 meters and 50 meters between fire teams. The lead fire team is far enough ahead to detect or engage the enemy before the opposing force can engage the remainder of the squad, but close enough to still be supported with small arms fire from the trail fire team.

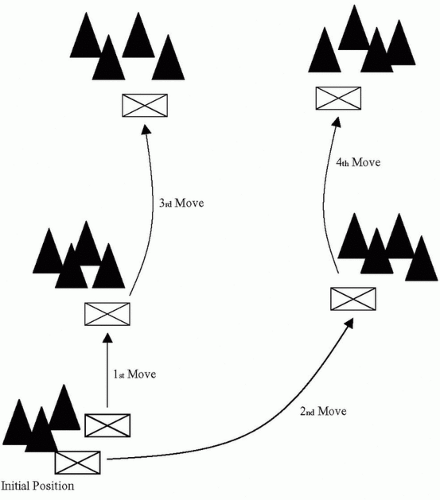

Bounding overwatch is used when enemy contact is expected. While it provides the most control, dispersion, and security of the three movement techniques, it is also the slowest. Although the distance between individual soldiers remains roughly 20 meters, the distance between fire teams will vary with the terrain and other operational conditions. One fire team moves forward (bounds), while the other team overwatches from a position that can cover the route by fire. If the bounding team is engaged, the overwatch team provides supporting fires and movement. The length of a bound can vary with terrain, visibility, and required control, but must remain within the supporting range of the overwatch team. Teams can bound successively (Fig. 2.5) or alternately (Fig. 2.6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree