INTRODUCTION

The human neck contains numerous vital structures. Both blunt and penetrating injuries can damage structures from many organ systems. The challenge is to treat immediate, life-threatening complications of neck injury, such as airway compromise and hemorrhage, and also to recognize subtle signs of serious pathology.

ANATOMY

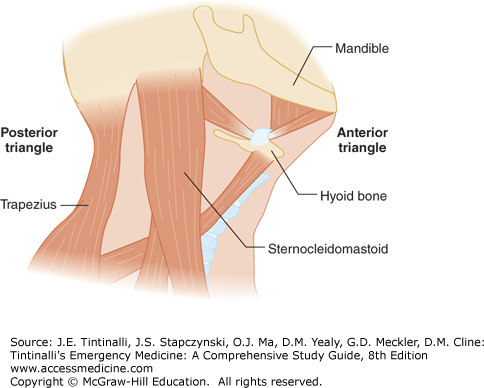

The neck is anatomically defined by triangles, zones, and fascial planes. Each sternocleidomastoid muscle separates the neck into two descriptive triangles, anterior and posterior (Figure 260-1). The posterior triangle is bordered by the anterior surface of the trapezius, posterior surface of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the middle third of the clavicle. The anterior triangle is formed by the borders of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, inferior mandible, and midline of the neck. Most vital structures are contained within the anterior triangle.

The anterior triangle is further subdivided into three horizontal zones (Figure 260-2), which have historically determined whether a patient undergoes mandatory surgical exploration or further diagnostic evaluation.1 Using this classification system, the index of suspicion for injury to a particular structure is dictated by the zone (Table 260-1). Classically, zone II injuries undergo surgical exploration; zone I and III wounds undergo further evaluation. This zone-based approach assumes a direct correlation between the site of the external wound and damage to deep structures; however, the trajectory of the penetrating object can be difficult to determine clinically, and nearly half traverse multiple zones.2,3,4

| Neck Zone | Anatomic Boundaries | Structures |

|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | Clavicles to the cricoid cartilage | Proximal carotid vertebral arteries Major thoracic vessels Superior mediastinum Lungs Esophagus Trachea Thoracic duct Spinal cord |

| Zone 2 | Cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible | Carotid and vertebral arteries Jugular veins Esophagus Trachea Larynx Spinal cord |

| Zone 3 | Angle of the mandible and the base of the skull | Distal carotid and vertebral arteries Pharynx Spinal cord |

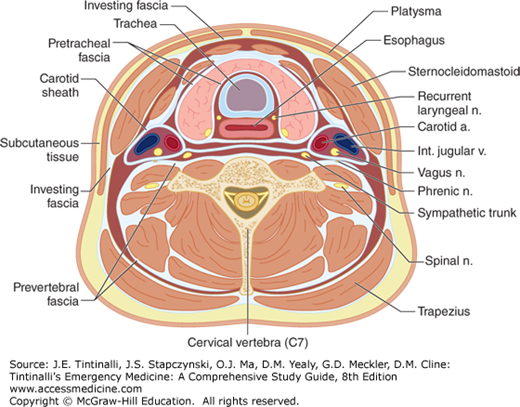

Finally, the neck is divided into fascial planes (Figure 260-3). The platysma is a thin muscle that stretches from the facial muscles to the thorax, demarcating superficial from deep wounds. Wounds that do not penetrate the platysma are not life threatening. The platysma muscle is enclosed within superficial fascia anteriorly and deep fascia posteriorly. The deep fascia is comprised of the investing, pretracheal, and prevertebral fascia and the carotid sheath.5 These fascial layers compartmentalize neck structures and, thus, can prevent exsanguination by confining hematomas. Conversely, increased pressure from expanding hematoma or edema can compromise the airway. Further, the layers can serve as a conduit for infection tracking from the neck into the mediastinum.6

INITIAL MANAGEMENT OF NECK INJURIES

The initial management of neck trauma follows the Advanced Trauma Life Support Guidelines with the systematic Airway, Breathing, Circulation, and Disability approach. Perform a primary survey to identify and treat immediate life-threatening injuries, followed by a secondary survey to discover further injuries.7

Many patients with neck trauma have signs and symptoms of airway compromise.8 Patients with shock, airway obstruction, impending airway collapse, or altered mental status require immediate airway control (Table 260-2). Although there is disagreement about the timing of definitive airway management in less emergent patients, airway anatomic distortion can progress rapidly. Promptly intubate any patient at risk for airway compromise (Table 260-3).9 Assume a difficult airway in a patient with neck trauma. Keep all your adjuncts to intubation, as well as a secondary means of securing the airway, readily available.

Progressive neck swelling Voice changes Progressive symptoms Massive subcutaneous emphysema of the neck Tracheal shift Alteration in mental status Expanding neck hematoma Need to transfer symptomatic patient Symptomatic patient with anticipated prolonged time away from ED |

Rapid-sequence orotracheal intubation is the preferred modality for securing the airway in patients with neck trauma and is successful in 98% of patients.10,11 When bag-mask ventilation proves difficult due to airway distortion or physical characteristics, perform an awake, orotracheal intubation using a sedative without a paralytic. Anticipate difficulty with bag-mask ventilation in patients with facial hair precluding a seal; unsTable mid-facial fractures; airway obstruction from blood, vomitus, or expanding hematoma; subcutaneous emphysema; or an open laryngeal injury that allows external passage of air.6

Video laryngoscope–guided intubation12 and endotracheal intubation over a fiberoptic bronchoscope are useful techniques to secure the airway.10,13,14

The laryngeal mask airway is a bridging device but is contraindicated in patients with significant airway distortion. Even if effective, the laryngeal mask airway is only a temporary method for ventilating trauma patients, not a definitive airway.7

A surgical cricothyrotomy, or needle-cricothyrotomy if the patient is younger than 8 years of age, is generally the last step in the failed airway management. Patients with neck trauma are at increased risked for requiring a surgical cricothyrotomy due to disruption of the laryngotracheal anatomy.13 Although there are no absolute contraindications to cricothyrotomy, relative contraindications include suspected or known tracheal transection, fractured larynx, or laryngotracheal disruption with retraction of the distal segment into the mediastinum. Tracheal transection can occur in patients with a “clothesline injury.” In such patients, pharmacologic paralysis may cause loss of muscle tone with disruption of the proximal and distal tracheal segments.6 If the patient has an open laryngeal disruption, you can perform direct intubation through the wound into the distal segment.11 If other airway techniques are unsuccessful, however, tracheostomy is indicated.10

Pneumothorax and hemothorax are present in up to 20% of patients with penetrating neck trauma.15 Auscultate for the presence or absence of breath sounds during the primary survey. Suspect tension pneumothorax in patients with unilateral breath sounds, hypotension, and respiratory distress, and treat with needle decompression and/or placement of a thoracostomy tube.6 Provide continuous pulse oximetry monitoring and supplemental oxygen.

Exsanguination is the proximate cause of death in most penetrating neck injury victims,8 and massive bleeding from trauma kills more rapidly than an unsTable airway. Control hemorrhage by applying direct pressure to bleeding wounds. Be careful not to simultaneously occlude both carotid arteries or obstruct the patient’s airway. Do not blindly clamp vessels in the ED because this practice can lead to cerebral ischemia or nerve injury.6 If life-threatening hemorrhage is not controlled by simple pressure, you can insert a Foley catheter into the wound tract and inflate the balloon until bleeding stops or you encounter resistance.16 Animal model and anecdotal tactical medicine experience suggests that topical hemostatic static agents may improve the survival of patients with bleeding not controlled by pressure. Although the ideal hemostatic agent has not been identified, hemostatic dressings combined with direct pressure appear to decrease blood loss and increase patient survival.17 Hemostatic dressings may benefit patients with uncontrolled bleeding who need transfer to another hospital for definitive care. Patients with uncontrolled hemorrhage despite these attempts require immediate surgery.18 If subclavian vessels are involved, uncontrolled hemorrhage in zone I injuries may require emergent thoracotomy.19

UnsTable cervical spine injury is uncommon in awake, neurologically intact patients with an isolated penetrating neck injury.20 Vertebral fractures and spinal cord injury are exceedingly rare in patients with isolated stab wounds to the neck.21 Therefore, cervical collar placement may, in fact, be detrimental by obscuring the injury and increasing the difficulty of hemorrhage control and intubation.20 Cervical collars should not be maintained at the expense of monitoring the injury or life-saving procedures.

Spinal cord damage is more likely from gunshot wounds, and cord damage is sustained at the time of injury. Deficits, which are usually permanent, should be evident at time of presentation unless the patient has an altered sensorium. Place a cervical collar on patients with a neurologic deficit or altered mental status precluding exam, after checking the neck to identify any penetrating injuries, vascular thrills or bruits, or bleeding or hematoma.22,23

However, patients with blunt neck trauma frequently have cervical spine fractures, so maintain cervical spine immobilization in such injuries.24

Although conventional radiographs of the chest and neck may suggest a variety of pathologies in the patient with neck trauma (Table 260-4),7,18,25,26 most patients with penetrating or blunt neck trauma will require advanced imaging in the form of multidetector CT angiography (MDCTA), MRI, or magnetic resonance angiography. Obtain a chest radiograph to evaluate for pneumothorax and hemothorax in patients with neck trauma because there is a high incidence of these thoracic complications. In addition, pneumothorax and hemothorax can be detected rapidly by bedside ultrasound.27 Do not delay transfer of patients between hospitals or to the operating room to obtain conventional radiographs of the neck.

Chest radiograph

Soft tissue neck radiograph

Cervical spine radiograph (anteroposterior, lateral, and odontoid)

|

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Any wound deep to the platysma raises concern for damage to the vital structures of the neck. Simple diagnostic maneuvers add valuable information to the physical exam. Instruct awake and cooperative patients to cough (to check for hemoptysis), to swallow saliva (to assess for dysphagia from esophageal injury), and to speak (to evaluate for laryngeal fracture).6 In patients with penetrating neck trauma, a careful, structured physical exam is more than 95% sensitive for detecting clinically significant vascular and aerodigestive injuries.23 The physical exam is most accurate for identifying arterial injuries; conversely, esophageal and venous injuries may be missed. Assess the patient for “hard” and “soft” signs of injury (Table 260-5).15,28 Nine out of 10 patients with hard signs will have an injury requiring repair and should be rapidly transferred to the operating room or angiography suite. If your institution does not have the requisite surgical or diagnostic capabilities readily available, transfer to an appropriate hospital. Presence of soft signs increases suspicion of structural damage and indicates the need for additional diagnostic evaluation; however, only a minority of patients with soft signs will have a clinically significant injury.15,29,30,31

| Hard | Soft |

|---|---|

Vascular injury Shock unresponsive to initial fluid therapy Active arterial bleeding Pulse deficit Pulsatile or expanding hematoma Thrill or bruit | Hypotension in field History of arterial bleeding Nonpulsatile or nonexpanding hematoma Proximity wounds |

Laryngotracheal injury Stridor Hemoptysis Dysphonia Air or bubbling in wound Airway obstruction | Hoarseness Neck tenderness Subcutaneous emphysema Cervical ecchymosis or hematoma Tracheal deviation or cartilaginous step-off Laryngeal edema or hematoma Restricted vocal cord mobility |

Pharyngoesophageal injury | Odynophagia Subcutaneous emphysema Dysphagia Hematemesis Blood in the mouth Saliva draining from wound Severe neck tenderness Prevertebral air Transmidline trajectory |

PENETRATING NECK INJURY

Although penetrating neck wounds account for only 1% of traumatic injuries, the mortality rate is as high as 10%.8 Gunshot wounds and stab wounds are the predominant mechanisms of injury, whereas flying debris and sharp object impalement are less frequent causes.8,18,32 Patients often have significant concurrent wounds to the head, chest, or abdomen.8,18,28,32

Gunshot wounds are more likely than stab wounds to cause vascular and aerodigestive system damage. Transcervical gunshot wounds have at least a 70% chance of substantial associated injuries.28,33 Vascular injuries are the most common cervical injury and the leading cause of death from penetrating neck trauma.18 The remainder of associated neck injuries are split among spinal cord, aerodigestive tract, and peripheral nerve injuries.15,28,32

There is no debate regarding the treatment of unsTable patients with clear evidence of vascular or aerodigestive injury—this group of patients should undergo invasive intervention.2,8,29,32 Controversy arises in two areas concerning the management of sTable patients:

Should all zone II injuries undergo mandatory exploration?

Should all zone I and III injuries undergo a specific, extensive battery of diagnostic testing?

Historically, all zone II injuries were surgically explored. This aggressive practice began during World War II as a response to a high incidence of missed injuries and mortality, but selective management is generally recommended today to minimize unnecessary surgery.34 Zone II is the most commonly injured area and is easily accessed surgically.29,32 Exposure and vascular control are more difficult for zone I and III injures, so most patients with zone I and III injuries undergo angiography and endoscopy to determine the need for operative intervention.35

The movement toward selective management rather than mandatory exploration began in response to the high rate of negative neck explorations. Furthermore, advocates of a more conservative methodology cite the sensitivity of physical exam in detecting clinically significant injuries. Contrarians maintain concerns about missed lethal injuries when relying solely on the clinical exam.36,37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree