INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Isolated trauma to an extremity with associated vascular injury has nearly a 10% rate of mortality or limb loss.1 Injuries involving the lower extremities are more common than injuries involving the upper extremities. The two most commonly injured blood vessels are the femoral and popliteal vessels.2 Penetrating trauma with early shock from proximal arterial hemorrhage is more likely to lead to mortality. Blunt distal extremity trauma with associated distal vascular injury is more commonly involved in early limb loss and amputations.

Advances in diagnostic imaging3 and surgical management have dramatically reduced the rate of limb loss and disability due to limb ischemia.4 The extent of injury to extremity nerves, bones, and soft tissues now determines if the limb can be surgically salvaged. Identifying and detecting which injuries require surgical evaluation and/or imaging are essential skills for emergency physicians.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Gunshot and knife wounds are the two most common causes of penetrating trauma. Stab wounds have a more predictable pattern of injury, making them more straightforward to manage. Gunshot injuries are more difficult to evaluate due to the extent of tissue damage and wider range of patterns of injury. More sophisticated vascular surgical repair techniques of arterial injuries,5 advances made during military conflicts, improved imaging, and other factors have led to a decreased rate of limb amputations and limb disability associated with penetrating trauma.6

CLINICAL FEATURES

Perform the primary trauma survey, immediate resuscitation, and secondary survey before focusing on injuries to the extremities. Apply direct pressure, pressure dressings, or a tourniquet to any actively bleeding extremity (see chapter 254, “Trauma in Adults,” and “Tourniquets”). Do not get distracted or deviate from the initial trauma management because associated injuries to other areas of the body are common with penetrating injuries. After identifying an injury during the secondary survey, thoroughly evaluate the affected extremity for vascular integrity, nerve function, skeletal injury, and soft tissue injury. The rapid evaluation of extremities for associated arterial injury is critically important for the management of these injuries. Note any hard or soft signs of vascular injury (Table 266-1). Use a Doppler flow device to detect a pulse if distal pulses cannot be palpated.

Hard signs Absent or diminished distal pulses Obvious arterial bleeding Large expanding or pulsatile hematoma Audible bruit Palpable thrill Distal ischemia (pain, pallor, paralysis, paresthesias, coolness) Soft signs Small, stable hematoma Injury to anatomically related nerve Unexplained hypotension History of hemorrhage Proximity of injury to major vascular structures Complex fracture |

Thoroughly evaluate nerve, tendon, and muscle function during the physical exam (Table 266-2). Pain on palpation or movement of bony structures or obvious deformities suggests an underlying fracture. Note any intra-articular hematomas or other signs of joint injury. Measure soft tissue lacerations and other associated injuries with a tape measure or ruler. Accurately describe injuries to consultants because measurement of the injury may change management in some situations.7

| Nerve | Test of Motor Function | Test for Sensation |

|---|---|---|

| Axillary (C5-C6) | Arm abduction | Lateral aspect of shoulder |

| Arm internal, external rotation | ||

| Musculocutaneous (C5-C6) | Forearm flexion | Lateral forearm |

| Radial (C5-C8) | Forearm, wrist, and finger extension | Dorsoradial hand, thumb |

| Median (C6-T1) | Wrist flexion, finger adduction | Volar aspect of thumb and index finger |

| Ulnar (C7-T1) | Finger abduction | Volar aspect of little finger |

| Femoral (L1-L4) | Knee extension | |

| Obturator (L2-L4) | Hip adduction | |

| Superior gluteal (L4-S1) | Hip abduction | |

| Sciatic (L4-S3) | Knee flexion | |

| Deep peroneal (L4-S1) | Ankle and great toe dorsiflexion | |

| Superficial peroneal (L5-S1) | Foot eversion | |

| Tibial (L5-S2) | Ankle plantar flexion | |

| Posterior tibial (L5-S2) | Great toe plantar flexion | |

| Spinal L4 | Medial calf | |

| Spinal L5 | Dorsal foot | |

| Spinal S1 | Lateral plantar foot |

In the absence of hard signs, determine the ankle-brachial index for any injured extremity along with the nonaffected extremity for comparison. An ankle-brachial index reading of <0.9 is considered abnormal and is concerning for associated arterial injury. The ankle-brachial index reliably detects occlusive arterial injury with accuracy as high as 95%, but the true sensitivity and specificity have varied in clinical studies.8,9 Use caution in relying on a normal ankle-brachial index to rule out arterial injury, because it does not detect nonocclusive arterial injuries such as intimal flaps, focal narrowings, small pseudoaneurysms, and arteriovenous fistulas in up to 10% of cases.10

DIAGNOSIS

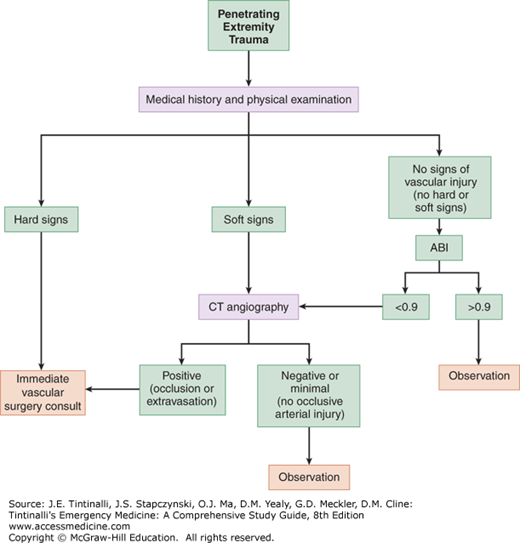

Diagnosis of associated injuries depends on a complete history and physical exam of the involved extremity. If any hard signs of vascular injury are present, then consult vascular surgery immediately. If there are any soft signs of vascular injury and/or if the ankle-brachial index is <0.9, then order imaging tests to evaluate for associated vascular injuries, or transfer to an institution with vascular care capability (Figure 266-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree