8 Trauma Resuscitation

• The approach to trauma resuscitation is based on the assumption that all severely injured patients can initially be evaluated and treated with the same set of guidelines.

• Regardless of the specific injury, these guidelines focus on the broader concept of sustaining life by maximizing oxygenation, ventilation, and perfusion—the ABCs of trauma resuscitation.

Epidemiology

Traumatic injury is a significant cause of death and disability worldwide, especially in the younger population. In the United States, unintentional injury is the leading cause of death in the age range between 1 and 44 years.1 Approximately half of trauma-related deaths occur at the time of injury or before the patient reaches the hospital. Another 30% of traumatic deaths may occur in the first few hours after the event. It is this severely injured, but salvageable population that should be immediately evaluated and treated with the trauma resuscitation paradigm.

Perspective

Shock in trauma patients is often due to hemorrhagic blood loss, but it may also be caused by damage to the heart, great vessels, or lungs or by hemodynamic compromise from fat emboli, ischemia, or neurogenic shock (Box 8.1).

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The American College of Surgeons and many emergency medical service systems have adopted algorithms based on clinical signs and symptoms for transport to a trauma center.2 These signs and symptoms identify patients at high risk for injury and are based on early physiologic changes, anatomic criteria, or a mechanism with a high likelihood of significant injury (Box 8.2). Along with the trauma center criteria, in each of the major anatomic areas there are important clues to potentially life- and limb-threatening injures (Table 8.1).

Box 8.2 Criteria for the Identification of Traumatized Patients with a High Probability of Injury Requiring Transport to a Trauma Center

Mechanism of Injury

Table 8.1 Signs of Significant Injuries in Trauma Patients

| ANATOMIC AREA | MOST THREATENING SIGNS |

|---|---|

| Head | Cerebrospinal fluid leak |

| Raccoon eyes | |

| Battle sign | |

| Hemotympanum | |

| Anisocoria | |

| Neck | Expanding hematoma |

| Thrill or murmur | |

| Subcutaneous air | |

| Trachea deviated from midline | |

| Pulsatile hemorrhage | |

| Spine | Paralysis |

| Paresthesias | |

| Decreased rectal tone | |

| Chest | Subcutaneous air |

| Multiple rib fractures | |

| Sucking chest wound | |

| Asymmetric chest rise | |

| Abdomen | Abdominal wall bruising |

| Distended abdomen | |

| Pelvis | Unstable pelvis |

| Large expanding hematoma | |

| Blood at urethral meatus | |

| Scrotal hematoma | |

| Bone fragments in vaginal vault or rectum | |

| High-riding prostate | |

| Extremities | Pallor |

| Decrease in or absence of pulses | |

| Weakness or paralysis |

Head injuries may result in a decreased level of consciousness leading to loss of airway protection or respiratory drive. Head injuries can also precipitate hemorrhagic shock as a result of the abundant vascular supply of the face and scalp. Because of their proportionally larger heads, children can lose a significant amount of blood with closed intracranial hemorrhage. For further specific evaluation and treatment of head injuries, see Chapter 73.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Primary Survey

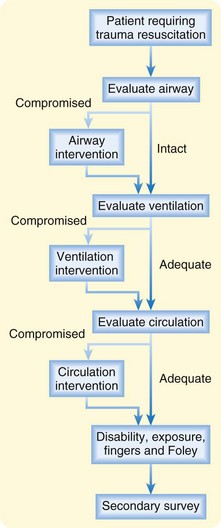

Although performance of the primary survey should be fluid and may involve multiple individuals performing multiple actions simultaneously, the components of the primary survey can be broken down into six sequential steps: airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure, and fingers or Foley (ABCDEF) (see Fig. 8-1 and Priority Actions box).

If an indication for intervention is discovered during the primary survey, treatment should be initiated and the primary survey restarted from the beginning (Fig. 8.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree