Trauma in Pregnancy

Bonnie Lau and Susan B. Promes

Significant trauma affects approximately 7% of pregnant women (1). In fact, trauma was reported to be the leading cause of death during pregnancy in at least one series (2). Statistically, pregnant women sustain approximately 4.1 trauma-related hospitalizations per 1,000 deliveries (3). The pregnant trauma patient presents a unique challenge to the emergency department (ED) team caring for her. Not only is the physician caring for two patients, but both of the patients have their own unique needs. In general, when faced with a pregnant trauma patient, the emergency physician should resuscitate the mother first. The well-being of the unborn fetus is dependent upon the hemodynamic stability of the mother.

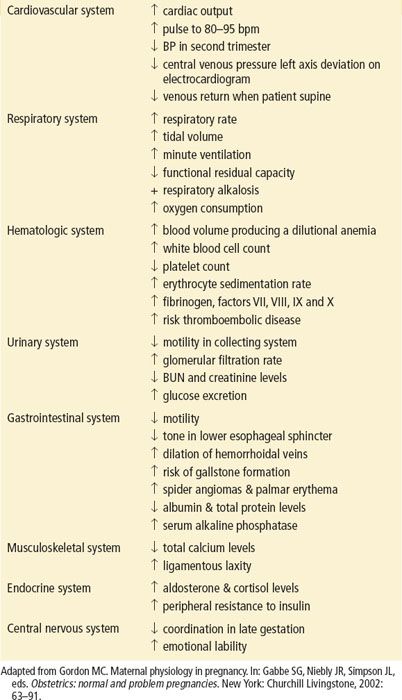

It is imperative that the physician caring for the gravid woman be aware of the physiologic changes that occur during pregnancy and the impact these changes may have on the resuscitation of the pregnant woman and her unborn fetus (eTable 52.1). This knowledge will be critical to the evaluation and treatment of the woman and her unborn child.

eTABLE 52.1

Changes in Maternal Physiology During Pregnancy

Airway. Although airway anatomy does not change significantly, progesterone causes smooth muscle relaxation, affecting the lower esophageal sphincter and increasing the risk of aspiration.

Breathing. The diaphragm is gradually pushed up 3 to 4 cm during pregnancy, causing a 25% decrease in functional residual capacity and resulting in decreased maternal oxygen reserve. Pulmonary function is further compromised by increased oxygen consumption. Starting in the first trimester, stimulation of the medullary respiratory center by progesterone increases minute ventilation by up to 50% (a result of increased tidal volume). This is accompanied by a 10-mm Hg increase in PO2, a 10-mm Hg decrease in PCO2, and a compensatory decrease in bicarbonate to about 19.5 mEq/L. These physiologic changes result in less respiratory reserve in the pregnant trauma patient.

Circulation. Pregnancy is a high-flow, low-resistance state of cardiovascular homeostasis. Heart rate increases until the end of the second trimester, when it plateaus at 10 to 15 beats above baseline. Systolic, and to a greater extent diastolic, blood pressure decrease during the first and second trimesters, returning to prepregnancy baseline levels during the third trimester. Cardiac output increases by 40% by the end of the first trimester and persists at this level, causing a cardiac flow murmur in 90% of pregnant women. By the third trimester, there is increased vascular congestion in the pelvis and a 50% decrease in the velocity of venous flow in the lower limbs (4). These changes predispose the gravid patient to deep venous thrombosis as well as increased bleeding from lower extremity and pelvic trauma.

In addition, several hematologic changes accompany pregnancy. A 50% increase in blood volume and concomitant increase in red blood cell mass by only 20% to 30% results in a 3% to 6% drop in hematocrit. The white blood cell count increases to 12,000 to 18,000/μL by the second trimester and may increase to 25,000/μL with stress. The prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times are somewhat decreased. Coagulation factors rise gradually and exceed fibrinolytic activity by the third trimester.

The fetus has a higher hemoglobin concentration than the mother, and fetal hemoglobin has a higher affinity for oxygen. As a result, fetal oxygen consumption does not decrease until oxygen delivery decreases by 50% (5). This allows the fetus to tolerate brief periods of maternal hypoxia and hypoperfusion. In late pregnancy, the fetus is capable of redistributing blood to the heart and brain (6).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Critically ill pregnant trauma patients may present with normal vital signs due to the physiologic changes that occur in pregnancy; this should not give the emergency physician a false sense of security. Pregnant women have increased blood volume as they near term, so blood loss must be excessive before hypotension occurs. Abdominal pain in the pregnant trauma patient may be due to common intra-abdominal injuries associated with blunt trauma. Other causes of life-threatening problems include uterine rupture, placental abruption, and premature labor.

Pregnant trauma patients tend to have a slightly different injury pattern when compared to the general trauma population, with increased intra-abdominal injuries and decreased traumatic brain injuries (7). In penetrating trauma, this may be due to changes in maternal anatomy with increasing gestational age. The diaphragm and intra-abdominal contents are displaced upward by the enlarging uterus; hence, injury patterns will vary from the general population. For example, someone with a stab wound to the left upper quadrant is at increased risk for intestinal injury because the uterus displaces the intestinal contents superiorly.

Whether the pregnant patient is involved in blunt or penetrating trauma, the fetus in addition to the mother is at risk for injury. Even minor maternal injuries can lead to placental abruption, uterine rupture, fetal–maternal hemorrhage, and premature birth. The emergency physician should look for signs of occult injury that are manifested by uterine irritability, vaginal bleeding, and fetal tachycardia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The emergency physician caring for the pregnant trauma patient should first consider the typical injury patterns that are associated with a given mechanism of injury. The pregnant trauma patient is not immune to common traumatic injuries. While the emergency physician is evaluating the pregnant patient for common injuries, the physician should also consider the unique role the gravid uterus plays in the traumatic event. As the uterus enlarges during pregnancy, changes in intra-abdominal anatomy alter the injury pattern. For example, the diaphragm moves cephalad into the thoracic cavity. Subsequently, in a pregnant patient who sustains a penetrating injury to the chest, the physician should have a greater suspicion for a diaphragmatic injury. In addition, the large gravid uterus displaces the intra-abdominal contents, making bowel injuries less common and injury to the uterus more common in blunt trauma. A few important injuries associated with pregnancy include placental abruption, uterine rupture, maternal–fetal hemorrhage, and premature labor. The greater the severity of maternal trauma, the more likely a significant fetal insult will occur. Pearlman and Tintinalli (8) reported a fetal loss rate of 41% with life-threatening maternal injuries while the fetal loss rate was 1.6% with nonlife-threatening injuries.

Seizures in trauma patients are generally associated with head injuries. However, in the gravid trauma patient, the emergency physician must also consider eclampsia as the etiology of the seizure and subsequent trauma.

ED EVALUATION

As the survival of the fetus is dependent upon maternal resuscitation, the evaluation of the pregnant trauma patient should proceed in a step-wise fashion. Advanced trauma life support principles should be followed as in the nonpregnant trauma patient. However, during the primary and secondary trauma surveys, the emergency physician must apply a detailed understanding of the physiologic changes that occur in the pregnant state to detect potentially life-threatening conditions. The airway must be managed aggressively. All pregnant trauma patients should be placed on oxygen, since oxygen consumption is increased with pregnancy, and it is important to avoid fetal hypoxia. When evaluating the circulatory status, the physician should remember that the second-trimester pregnant patient without significant injuries may have an elevated heart rate and lower blood pressure. Conversely, she may also have significant life-threatening hemorrhage without alteration in vital signs due to the physiologic increase in cardiac output and intravascular volume.

After the primary survey, a complete history should be obtained, including last menstrual period, estimated date of delivery, previous pregnancy history, and any problems associated with the pregnancy.

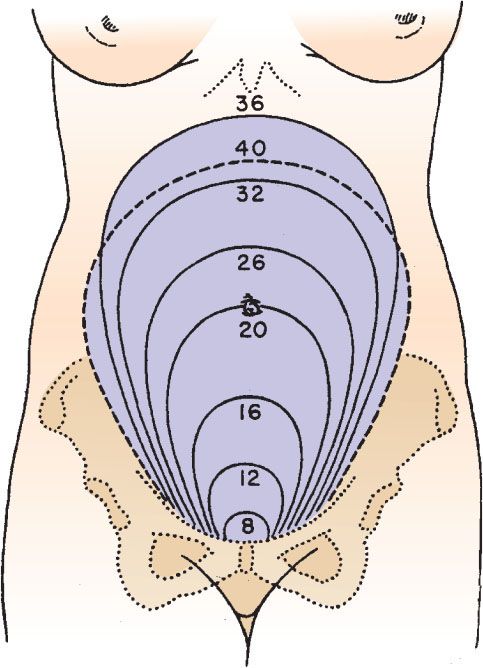

The fetus is evaluated during the secondary survey. The fundal height should be assessed, recognizing that a fundal height at or above the level of the umbilicus may indicate a potentially viable fetus. The distance between the symphysis pubis and the uterine fundus measured in centimeters approximates gestational age in weeks (Fig. 52.1). The threshold for fetal viability is 23 to 24 weeks depending on the resources available at the facility to care for the neonate (9). The presence of fetal heart tones should be documented. In patients at 20 weeks or more gestation, cardiotocographic monitoring should be obtained as soon as possible. This gives the physician information regarding fetal–maternal well-being. A normal fetal heart rate is between 120 and 160 bpm. Fetal tachycardia, fetal bradycardia, contractions, loss of beat-to-beat variability, or late or prolonged decelerations after contractions may be signs of fetal distress heralding such pathologic states as placental abruption or occult maternal shock. If the patient has vaginal bleeding, then a sterile vaginal speculum examination should be performed to identify the source of bleeding, being mindful of potential placenta previa. Aside from evaluation of the pregnancy itself, a speculum examination may reveal signs of genitourinary trauma such as lacerations from pelvic fractures or penetrating trauma.

FIGURE 52.1 The height of the uterine fundus at different gestational dates.