INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Trauma remains the leading cause of nonobstetric morbidity and mortality in pregnant women.1 The severity of maternal injuries may be a poor predictor of fetal distress and outcome after a traumatic event (even minor ones). Trauma during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of preterm labor, placental abruption, fetomaternal hemorrhage, and pregnancy loss. Achieving successful outcomes for both mother and fetus requires a collaborative effort by the prehospital provider, emergency physician, trauma surgeon, obstetrician, and neonatologist.

Trauma during pregnancy is common. One study estimated that 32,810 pregnant women sustain injuries in motor vehicle crashes every year in the United States, a rate of 9 per 1000 live births.2 Motor vehicle crashes are the most common cause of blunt abdominal trauma, accounting for up to 70% of acute injuries. This is followed by falls and direct assault in decreasing order of frequency.3 The incidence of falls appears to increase with the advancement of pregnancy, presumably due to alterations in maternal balance and coordination. Penetrating injuries are less common than blunt trauma during pregnancy.

PHYSIOLOGY OF PREGNANCY

Physiologic changes in pregnancy are discussed in detail in chapter 25, “Resuscitation in Pregnancy.” In addition to normal physiologic changes, conditions such as pregnancy-induced hypertension, placenta previa, pre-eclampsia, and eclampsia may significantly alter the presentation and complicate evaluation and treatment in the setting of trauma (see chapter 100, “Maternal Emergencies after 20 Weeks of Pregnancy and in the Postpartum Period”).

Table 25-1 summarizes important physiologic changes in pregnancy that affect resuscitation. Maternal blood volume expands at approximately week 10 of gestation and peaks at about a 45% increase from baseline at week 28. Because plasma volume increases more than red cell mass, mild physiologic anemia may be evident. Cardiac output increases by 1.0 to 1.5 L/min at week 10 of pregnancy and remains elevated until the end of pregnancy. Heart rate in the mother is generally increased by 10 to 20 beats/min in the second trimester, accompanied by decreases in systolic and diastolic blood pressures of 10 to 15 mm Hg.

The relative hypervolemic state can mislead the clinician during maternal resuscitation after trauma and make clinical findings difficult to interpret. A pregnant patient may lose 30% to 35% of circulating blood volume before manifesting hypotension or clinical signs of shock. Uterine blood flow is directly proportional to maternal mean arterial pressure, so maintain and replace maternal blood volume aggressively and adequately.

After week 12 of gestation, the uterus becomes an intra-abdominal organ, removing it from the relative protection of the maternal pelvis and making it susceptible to direct injury. The bladder moves anteriorly into the abdomen in the third trimester of pregnancy, increasing its vulnerability to injury. Uterine blood flow may increase to upward of 600 mL/min; severe maternal hemorrhage from uterine injury enters the equation at this point. The gravid uterus also causes passive stretching of the abdominal wall and peritoneum as it enlarges, and this may lead to diminished sensitivity to injury and irritation from intraperitoneal blood. At approximately weeks 18 to 20 of gestation, the expanding mass of the gravid uterus may put the mother at risk for the “supine hypotension syndrome,” in which venous return and cardiac output are diminished by compression of the maternal inferior vena cava in the supine position. The enlarging uterus may also cause engorgement of lower extremity and lower abdominal vessels, which predisposes the patient to severe retroperitoneal injury. Avoid placing IV lines in the femoral region and lower extremity because of inferior vena cava compression by the uterus and the possibility of pooling in engorged or injured pelvic veins.

As pregnancy progresses, the diaphragm elevates by as much as 4 cm, and tidal volume increases by 40% as residual volume diminishes by 25%. These changes may significantly impair the ability of a pregnant trauma patient to compensate for respiratory compromise and can result in rapid development of hypoxia from pulmonary disorders or during intubation. Consider diaphragmatic elevation when thoracostomy tube placement is indicated during maternal resuscitation.

Gastric emptying is delayed, increasing the likelihood of gastroesophageal reflux and the potential for aspiration from acute injuries or endotracheal intubation. The small bowel is moved upward in the abdomen by the enlarging uterus, which increases the chance of complex bowel injuries in penetrating trauma of the upper abdomen.4 The liver is typically unaffected by pregnancy, and the most common cause of abdominal hemorrhage remains splenic injury, as in nonpregnant patients.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Rapidly assess gestational age by palpating uterine fundal height. At week 12 of gestation, the uterine fundus is at or about the level of the pubic symphysis, and at week 20, it is at the umbilicus. The uterus then expands approximately 1 cm beyond the umbilicus per additional week of gestation. Assessing fetal age helps determine fetal viability. Gestation ≥24 weeks is compatible with fetal viability. Examine the abdomen and uterus for evidence of injury as well as for uterine tenderness or contractions. Placental abruption may be suggested by a rigid, boardlike uterus, or no signs may be evident at all.

Direct fetal injury is relatively rare in blunt abdominal trauma during the first trimester. When fetal injuries do occur, they are typically seen later in gestation and tend to involve the fetal skull and brain. Such injuries can be sustained in association with fractures to the maternal pelvis when the fetal head is engaged. When the uterus is penetrated by a sharp object or projectile, the fetus can be injured.

Uterine rupture accounts for <1% of all injuries in pregnancy and is more likely to occur during the late second and third trimesters and when there is direct and forceful impact on the uterus.3 The fetal mortality rate is high. The clinical presentation of uterine rupture is quite nonspecific, but loss of the palpable uterine contour, ease of palpation of fetal parts, or radiologic evidence of abnormal fetal location suggests the diagnosis.

Uterine irritability and the onset of preterm labor may be precipitated by acute abdominal trauma during pregnancy. The use of tocolytic agents to manage premature labor in pregnant trauma patients is not generally recommended, so consult an obstetrician before considering tocolytics. Tocolytic agents have numerous adverse side effects, such as fetal and maternal tachycardia, that may complicate trauma evaluation.

Placental abruption is second only to maternal death as the most common cause of fetal death (Figure 256-1). Placental abruption complicates 1% to 5% of minor injuries during pregnancy and up to 40% to 50% of major traumatic injuries. During direct abdominal or deceleration injury, intrauterine pressures increase, the relatively elastic uterus deforms at the relatively inelastic placenta, and the placenta shears from the uterine wall. Even “minor” maternal injuries such as minor motor vehicle crashes, falls, and assaults can be associated with placental abruption and sudden fetal demise.5 The most sensitive clinical finding for placental abruption after trauma is uterine irritability (more than three contractions per hour), most evident immediately after trauma, on initial presentation to the ED.5,6 Other clinical findings of placental abruption include abdominal pain, painful vaginal bleeding, and tetanic uterine contractions. Placental abruption may also lead to the introduction of placental products into the maternal circulation, stimulating disseminated intravascular coagulation or amniotic fluid embolism.

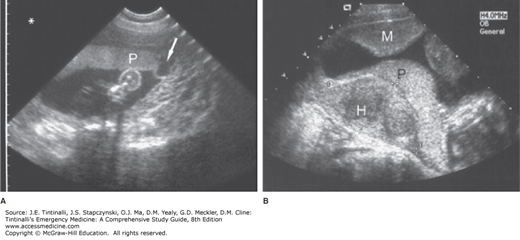

FIGURE 256-1.

A. Placental abruption. Transabdominal long-axis scan shows an anterior placenta with a contained marginal abruption (arrow). [Image used with permission of L. Sens and L. Green, Gulfcoast Ultrasound.] B. Placental abruption. Transabdominal scan, sagittal plane, demonstrating retroplacental hematoma (H) in an 18-week pregnancy. The placenta (P) is located on the posterior wall. A myometrial contraction (M) of the anterior wall is evident.

Fetomaternal hemorrhage is the entry of fetal red blood cells into the maternal blood stream and should be assumed in the setting of maternal trauma. If the mother is Rh negative and the fetus is Rh positive, if as little as 0.1 μL of fetal blood enters the maternal circulation, it can sensitize the mother7 and endanger the pregnancy and subsequent pregnancies. This is the basis for administering Rho(D) immunoglobulin to Rh-negative mothers after maternal trauma.

PREHOSPITAL CARE

Prehospital care providers should ask about the possibility of pregnancy when evaluating injured women of childbearing age. Prioritize attention to the fundamentals of resuscitation (airway, breathing, circulation) in the mother. Administer supplemental oxygen because compensation for hypoxia is limited in pregnancy. Similarly, consider early endotracheal intubation when indicated by the nature or severity of injuries. Establish peripheral IV lines, and provide 50% more volume than would be given to the nonpregnant patient.

For patients at >20 weeks of gestation who must be transported in the supine position or in whom spinal immobilization is indicated, place a wedge under the right hip area, tilting the patient approximately 30 degrees to the left, to prevent hypotension from inferior vena cava compression by the gravid uterus. Triage to a hospital with trauma, obstetric, and neonatal services if at all possible.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree