INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Trauma accounts for 41 million annual ED visits and 2.3 million hospital admissions across the United States. Trauma is the number one cause of death for Americans between age 1 and 44 years and is the number three cause of death overall.1 In all countries, the incidence of death from injury increases more than threefold with increasing poverty. For the 90% of patients who survive the initial trauma, the burden of ongoing morbidity from traumatic brain injury, loss of limb function, and ongoing pain is even more significant.

The major causes of death following trauma are head injury, chest injury, and major vascular injury. Trauma care should be organized according to the concepts of rapid assessment, triage, resuscitation, diagnosis, and therapeutic intervention.2 Worldwide, there are few countries or regions that have comprehensive systems of trauma care, from roadside to rehabilitation, and that incorporate effective injury prevention strategies.

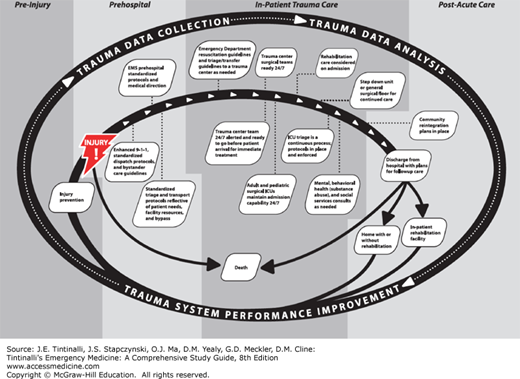

A systematic approach is required to reduce morbidity and mortality that occur after traumatic injury (Figure 254-1).

FIGURE 254-1.

Phases of a preplanned trauma care continuum. [From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Model Trauma System Planning and Evaluation. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. Available at: www.facs.org/trauma/tsepc/pdfs/mtspe.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2014.]

Recognizing the need to establish a system to triage injured patients rapidly to the most appropriate setting and the importance of promoting collaboration among emergency medicine, trauma surgery, and trauma care subspecialists, the U.S. Congress passed the Trauma Care Systems Planning and Development Act of 1990.3 This act provided for the development of a model trauma care system plan to serve as a reference document for each state in creating its own system. Each state must determine the appropriate facility for treatment of various types of injuries. Trauma centers are certified based on the institution’s commitment of personnel and resources to maintain a condition of readiness for the treatment of critically injured patients. Some states rely on a verification process offered by the American College of Surgeons for the designation of certain hospitals as trauma centers.2 In a well-run trauma center, the critically injured patient undergoes a multidisciplinary evaluation, and diagnostic and therapeutic interventions are performed with smooth transitions between the ED, diagnostic radiology suite, operating room, and postoperative intensive care setting. Table 254-1 details the requirements for designation as a Level 1 trauma center. A complete list of trauma center requirements is available at the American College of Surgeons website (http://www.facs.org/trauma/verificationhosp.html).

24-h availability of surgeons in all subspecialties (including cardiac surgery/bypass capability) 24-h availability of neuroradiology and hemodialysis Program that establishes and monitors effect of injury prevention and education efforts Organized trauma research program |

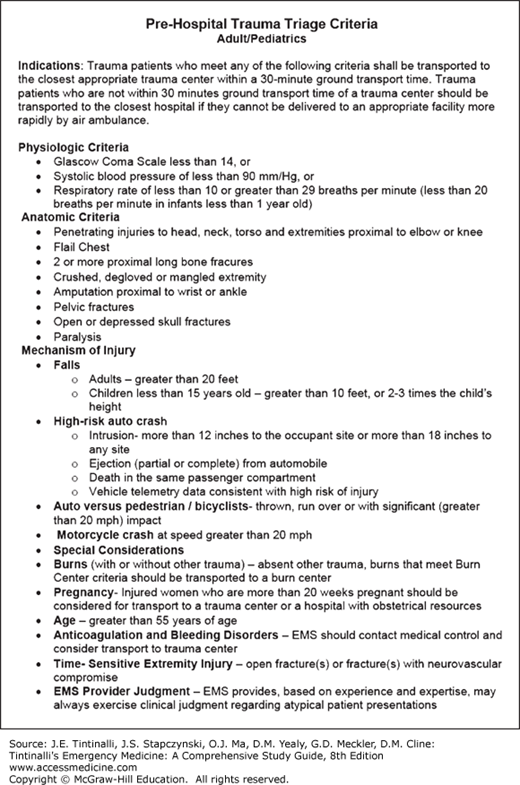

A well-functioning trauma system defines trauma centers with specific triage criteria, so that patients can be initially transported by EMS to these centers or transferred to trauma centers from other hospitals after stabilization (Table 254-2 and Figure 254-2). In accordance with the principles of advanced trauma life support, injured patients are assessed and treated based on their presenting vital signs, mental status, and mechanism of injury.4

Physiologic abnormalities

Injury pattern

Mechanism of injury

|

PRIMARY SURVEY

Prior to the patient’s arrival at the hospital, EMS providers should inform the receiving ED about the mechanism of trauma, suspected injuries, vital signs, clinical symptoms, examination findings, and treatments provided. In preparation for the patient’s arrival, ED staff should assign tasks to team members, prepare resuscitation and procedural equipment, and ensure the presence of surgical consultants and other care team members. For patients transported to EDs that are not trauma centers, consider immediately whether transfer to a trauma center is appropriate and what resuscitation or stabilization can or should be performed prior to transfer.

A focused history obtained from the patient, family members, witnesses, or prehospital providers may provide important information regarding circumstances of the injury (e.g., single-vehicle crash, fall from height, environmental exposure, smoke inhalation), ingestion of intoxicants, preexisting medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, depression, cardiac disease, pregnancy), and medication use (e.g., steroids, β-blockers, anticoagulants) that may suggest certain patterns of injury or the physiologic response to injury.

ED care of the trauma patient begins with an initial assessment for potentially serious injuries. A primary survey is undertaken quickly to identify and treat immediately life-threatening conditions, with simultaneous resuscitation and treatment. Specific injuries that should be immediately identified and addressed during the primary survey include airway obstruction, tension pneumothorax, massive internal or external hemorrhage, open pneumothorax, flail chest, and cardiac tamponade. After assessing the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation, perform a more thorough head-to-toe examination (the secondary survey) (Table 254-3). Follow the secondary survey with appropriate diagnostic testing, further therapeutic interventions, and disposition. When derangements are identified in any of the systems assessed in the primary survey, undertake treatment immediately.

Primary Survey (rapid identification and management of immediately life-threatening injuries) A. Airway and cervical spine Assess, clear, and protect airway: jaw thrust/chin lift, suctioning. Perform endotracheal intubation with in-line stabilization for patient with depressed level of consciousness or inability to protect airway. Create surgical airway if there is significant bleeding or obstruction or laryngoscopy cannot be performed. B. Breathing Ventilate with 100% oxygen; monitor oxygen saturation. Auscultate for breath sounds. Inspect thorax and neck for deviated trachea, open chest wounds, abnormal chest wall motion, and crepitus at neck or chest. Consider immediate needle thoracostomy for suspected tension pneumothorax. Consider tube thoracostomy for suspected hemopneumothorax. C. Circulation Assess for blood volume status: skin color, capillary refill, radial/femoral/carotid pulse, and blood pressure. Place two large-bore peripheral IV catheters. Begin rapid infusion of warm crystalloid solution, if indicated. Apply direct pressure to sites of brisk external bleeding. Consider central venous or interosseous access if peripheral sites are unavailable. Consider pericardiocentesis for suspected pericardial tamponade. Consider left lateral decubitus position in late-trimester pregnancy. D. Disability Perform screening neurologic and mental status examination, assessing:

Consider measurement of capillary blood glucose level in patients with altered mental status. E. Exposure Completely disrobe the patient, and inspect for burns and toxic exposures. Logroll patient, maintaining neutral position and in-line neck stabilization, to inspect and palpate thoracic spine, flank, back, and buttocks. Secondary Survey (head-to-toe examination for rapid identification and control of injuries or potential instability) Identify and control scalp wound bleeding with direct pressure, sutures, or surgical clips. Identify facial instability and potential for airway instability. Identify hemotympanum. Identify epistaxis or septal hematoma; consider tamponade or airway control if bleeding is profuse. Identify avulsed teeth or jaw instability. Evaluate for abdominal distention and tenderness. Identify penetrating chest, back, flank, or abdominal injuries. Assess for pelvic stability; consider pelvic wrap or sling. Inspect perineum for laceration or hematoma. Inspect urethral meatus for blood. Consider rectal examination for sphincter tone and gross blood. Assess peripheral pulses for vascular compromise. Identify extremity deformities, and immobilize open and closed fractures and dislocations. |

Determine airway patency by inspecting for foreign bodies or maxillofacial fractures that may result in airway obstruction. Perform a jaw thrust maneuver (simultaneously with in-line stabilization of the head and neck) and insert an oral or nasal airway as part of the first response to a patient with inadequate respiratory effort. Insertion of an oral airway may be difficult in patients with an active gag reflex. Avoid nasal airway insertion in patients with suspected basilar skull fractures. Whenever possible, use a two-person spinal stabilization technique in which one provider devotes undivided attention to maintaining in-line immobilization and preventing excessive movement of the cervical spine while the other manages the airway. If the patient vomits, logroll the patient and provide pharyngeal suction to prevent aspiration. Perform endotracheal intubation in comatose patients (Glasgow coma scale score between 3 and 8) to protect the airway and to prevent secondary brain injury from hypoxemia. Agitated trauma patients with head injury, hypoxia, or drug- or alcohol-induced delirium may be at risk for self-injury. Trauma patients are frequently difficult to intubate due to the need for neck immobilization, the presence of blood or vomitus, or upper airway injury. Video laryngoscopy devices are beneficial because they aid in vocal cord visualization while minimizing cervical spine manipulation. If anatomy or severe maxillofacial injury precludes endotracheal intubation, cricothyroidotomy may be needed. Use a rapid-sequence intubation technique for intubation (see chapter 29, “Intubation and Mechanical Ventilation”).

Clearance of the cervical spine from serious injury involves careful clinical assessment, with or without radiologic imaging. Not all patients require cervical spine radiographs. The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) criteria (Table 254-4)5 and the Canadian cervical spine rule (Table 254-5)6 are useful only in awake and alert patients and are not a substitute for good clinical judgment. Patients meeting NEXUS or Canadian criteria for low risk of cervical spine injury should undergo full examination of the cervical spine, including active range-of-motion testing in all directions along with a thorough neurologic examination.

Any high-risk factor that mandates radiography? (Age >64 y or dangerous mechanism or paresthesias in extremities) No | If Yes, radiography indicated |

Any low-risk factor that allows safe assessment of range of motion? (Simple rear-end collision or sitting position in the ED or ambulatory at any time or delayed onset of neck pain or absence of midline cervical spine tenderness) Yes | If No, radiography indicated |

Able to rotate neck actively? (45 degrees left and right) Yes | If No, radiography indicated |

| No radiography indicated |

If the patient is obtunded, assume a cervical spine injury until proven otherwise. Even when plain radiographs or CT images show normal findings, it is possible for a patient to have unstable ligamentous injuries. Therefore, maintain spinal immobilization during the resuscitation. Imaging of the spine should not delay urgent operative procedures because imaging results will not change the immediate management. CT of the cervical spine is the preferred initial imaging modality. For full discussion of cervical spine imaging and management in trauma, see chapter 258, “Spine Trauma.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree