TRANSPLANTATION EMERGENCIES

HEIDI C. WERNER, MD, MSHPEd, KARAN McBRIDE EMERICK, MD, MSCI, HENRY C. LIN, MD, AND MARYANNE R.K. CHRISANT, MD

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

Solid organ transplantation is an effective and acceptable form of therapy that results in pediatric patients living healthy lives in an immunocompromised state. These children are active and social, and as a result experience the usual range of pediatric ailments and conditions. They are also, however, subject to ailments unique to transplant patients because of their recipient status and need for daily immunosuppression. The survival and longevity of these patients improves with increased understanding of immune function, rejection, and medically induced tolerance. In emergent situations, the morbidity and mortality of these patients is directly related to prompt diagnosis and treatment.

KEY POINTS

In transplant patients, fever may be sign of infection or acute rejection.

In transplant patients, fever may be sign of infection or acute rejection.

Immunosuppressive medications put transplant patients at risk of adverse effects or altered metabolism of common therapies used in the emergency department (ED).

Immunosuppressive medications put transplant patients at risk of adverse effects or altered metabolism of common therapies used in the emergency department (ED).

Decisions about initiation of new therapies should be made in consultation with the transplant team.

Decisions about initiation of new therapies should be made in consultation with the transplant team.

RELATED CHAPTERS

Signs and Symptoms

• Abdominal Distension: Chapter 7

• Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Chapter 28

Medical, Surgical, and Trauma Emergencies

• Cardiac Emergencies: Chapter 94

POSTTRANSPLANT INFECTIOUS COMPLICATIONS

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Presentation of infectious conditions in a transplant recipient may range from benign to uncharacteristically severe.

• Early identification of infectious etiologies allows for directed treatment.

• Patients on immunosuppression may not mount fever or elevated white count.

• Significant infections, such as bacterial sepsis or varicella, may progress rapidly.

• Unusual infections should be considered in immunocompromised patients with clinical signs or symptoms.

• Avoid NSAIDs for antipyresis in patients taking calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) (cyclosporine, tacrolimus). In combination, these drugs can cause acute renal insufficiency.

• Fever and elevated aminotransferases may be a sign of infection, rejection, or venous thrombosis in the pediatric liver transplant patient.

Current Evidence

In the immediate posttransplant period, the transplant patient is at risk for bacterial, viral, and fungal infections. Etiologies of the increased infectious susceptibility include high-dose immunosuppression and indwelling central venous access. Bacterial sources of infection include wound infection, urinary tract infection, and central-line infections. Both gram-positive organisms, such as staphylococcal or streptococcal species, and gram-negative organisms, especially enteric species, may be the etiologic agents of these infections. The risk of fungal sepsis is highest in children who have received numerous courses of antibiotics or require multiple operative procedures. Viral infections in the posttransplant period are typically caused by members of the herpes virus family. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) serologies are routinely screened in both donor and recipient with prophylaxis typically required for CMV naïve recipients.

Following the immediate posttransplant period, there remains an increased incidence of opportunistic infections and increased severity of common childhood infections. Yet, most children post solid organ transplant retain enough immune function so that they are able to fight and recover from typical infections.

Goals of Treatment

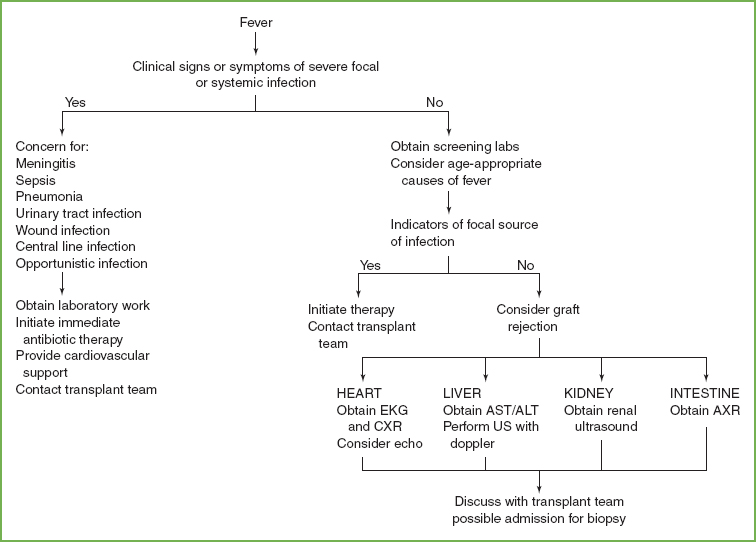

Infectious complications represent a common cause of posttransplant morbidity and mortality with fever being a primary presenting sign. However, a fever in a transplant patient may be a manifestation of infection, rejection, or anatomic complication. As such, the goal of treatment is to identify the etiology of fever and direct treatment appropriately. The most common etiologies are typical childhood infections such as otitis media, sinusitis, viral respiratory illnesses, pharyngitis, and gastroenteritis. For the majority of patients, the care is supportive and not substantially different than for nontransplant recipients. Careful attention must be paid, however, to hydration status, drug interactions with immunosuppressive medications, and establishing appropriate follow-up with the transplant team and the primary healthcare provider (Fig. 133.1).

FIGURE 133.1 Approach to the evaluation of fever in the transplant patient. EKG, electrocardiogram; US, ultrasound; CXR, chest radiograph; AXR, abdominal radiograph.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition

Fever in the posttransplant patient should prompt the emergency physician to look for infectious etiologies. The implications of a fever depend on time since transplant and degree of immunosuppression. In children on minimal immunosuppressive medications without an obvious source of fever and good caregiver follow-up, no further workup may be indicated. Common etiologies of fever are discussed below.

Otitis, Sinusitis, and Pharyngitis. As with immunocompetent children, head and neck infections comprise a major percentage of the pathology seen in the pediatric transplant population. One retrospective report found a 60% incidence of such infections, including sinusitis, otitis media, and pharyngitis/tonsillitis. Proper diagnosis is the cornerstone to successful management, and transplant recipients should still be tested for routine organisms. Consideration should be given to atypical or unusual pathogens especially in the face of a recurrent infection, an infection of long duration or an infection with an unusual presentation. Furthermore, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD), discussed below, can also present with malaise, fevers, lymphadenopathy, and tonsillar enlargement.

Gastrointestinal Infections. Transplant recipients presenting with simple diarrhea or vomiting may be managed conservatively with hydration and observation. They are at risk for renal insufficiency in the face of dehydration with ongoing CNI therapy. Furthermore, alterations in absorption of immunosuppressant medications can increase risk for rejection and graft loss. For prolonged gastrointestinal illnesses, one must consider parasitic infections including Cryptosporidium parvum or Giardia lamblia, and viral infections, especially CMV. Transplant recipients having recurrent or prolonged gastroenteritis with diarrhea should be tested for Clostridium difficile, which may prove to be indolent and difficult to clear, and may not be related to prior antibiotic use. In liver transplant patients, fever and ascites should warrant concern for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Respiratory Infections. Respiratory infections may be more severe in posttransplant patients. Respiratory viral panels should be used to evaluate for treatable viral infections such as influenza. It is unclear how effective these types of drugs are in reducing disease severity in the posttransplant population. Simple viral infections, such as rhinovirus, may cause lower as well as upper respiratory disease and require inpatient management. Clearance of these viruses may take many weeks and may prove challenging to treat. Chest radiographs are helpful if pneumonia or lower respiratory tract infection is suspected.

Opportunistic Infections. During the early posttransplant period, recipients typically receive prophylaxis for oral candidiasis, Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly Pneumocystis carinii) pneumonia, as well as CMV and EBV. Morbidity and mortality from invasive fungal infections are highest in the first 6 months post transplant, especially in patients who have had prior surgery or who are more debilitated and requiring support. Patients may present post hospital discharge, so any fevers, lingering illnesses, or concerning findings must be investigated. In a multicenter registry analysis from 2011, invasive fungal infections made up nearly 7% of the total number of posttransplant infections; 90% of the yeast infections were due to Candida species and 82% of the mold infections were due to Aspergillus species.

Herpes zoster can occur in posttransplant pediatric recipients, and may present with neuralgia as a presenting symptom. This can be progressive and incapacitating, with internal lesions as well as external. Generally, this disease requires admission and treatment with intravenous acyclovir until the lesions are crusted over. Varicella naïve patients may present to the ED after exposure and varicella immune globulin should be given if the time interval is favorable.

Triage Considerations

Transplant recipients presenting with infectious symptoms and fever should be seen and evaluated quickly as prompt diagnosis and treatment will forestall disease progression and obviate a potentially lethal situation. Vital signs and perfusion should be checked to monitor for signs of compensated and decompensated shock. Assessment of hydration status and treatment of hypovolemia is crucial. Antipyresis with acetaminophen and topical cooling will aid in patient comfort. Notably, NSAIDs should not be used as they limit renal perfusion. In combination with CNIs, and especially in the face of hypovolemia, they can cause acute renal failure. Direct and early communication with the transplant team physician or nurse is essential in obtaining necessary historical input and direction regarding potential sources and therapies.

Clinical Assessment

Given the many potential causes for fever in the posttransplant patient, a comprehensive history and physical examination must be performed. History should focus on sick contacts as well as obtaining a detailed posttransplant history including time since transplant, type and dose of immunosuppression, and any prior infectious exposures such as CMV and EBV. Conditions that impair the patient’s ability to take or absorb medications such as vomiting or diarrhea should be noted.

A comprehensive examination for source of fever is required including ENT, pulmonary, cardiovascular, and abdominal examinations on every patient regardless of chief complaint. Abdominal examinations should include an assessment for hepatosplenomegaly and other signs of liver involvement such as jaundice or ascites.

Management

Screening labs should include complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, liver function tests (LFTs), blood culture, urinalysis, and urine culture. Knowledge of a patient’s baseline laboratory values is useful for comparison. Neutropenia should prompt assessment for other infectious etiologies such as fungal or viral infections. Depending on recipient exposure and risk factors, EBV and CMV titers should also be obtained. For patients on CNIs, a trough level should be obtained as these medication levels may fluctuate during an infection. Other diagnostic testing to consider will be guided by the clinical presentation and may include inflammatory markers, viral panel, or stool cultures. In the child with fever and ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis should be considered and workup should include a diagnostic paracentesis with ascites fluid sent for culture, Gram stain, cell count, LDH, glucose, and protein.

If the patient is obviously septic or meningitic, blood cultures should be drawn and broad-spectrum antibiotics administered expeditiously. Headache, seizures, or neurologic changes in the setting of a fever are indications for a lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid cell count, as well as comprehensive stains and culture for bacteria, viruses, fungi, and acid-fast organisms, to be performed as part of the primary evaluation.

For liver transplant patients, in addition to laboratory assessment, an ultrasound examination with Doppler flow should be obtained to view arterial and venous blood flow to the graft and to assess the biliary tree for evidence of dilation, which suggests obstruction. If obstruction is suspected from the ultrasound evaluation, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) is usually necessary to image the biliary tree and biliary-enteric anastomosis. Prior to the PTC, the patient is given broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage for the common biliary pathogens (e.g., gram-negative enteric organisms). Ampicillin (200 mg/kg/day) and cefotaxime (100 mg/kg/day) are usually adequate. If the ultrasound evaluation is otherwise abnormal (i.e., demonstrating a fluid collection), the situation could require surgical revision of the biliary anastomosis or biliary stent placement either by the interventional radiologists or by open procedure by the transplant surgeons. If the ultrasound evaluation is normal and no source for the fever or increased LFTs are found, the patient may require admission for monitoring and possibly a liver biopsy to rule out rejection or viral infection.

For intestinal transplant patients, infectious complications are the leading cause of posttransplant mortality. Intra-abdominal infections or sepsis from gut translocation must be considered in these patients in the setting of fever.

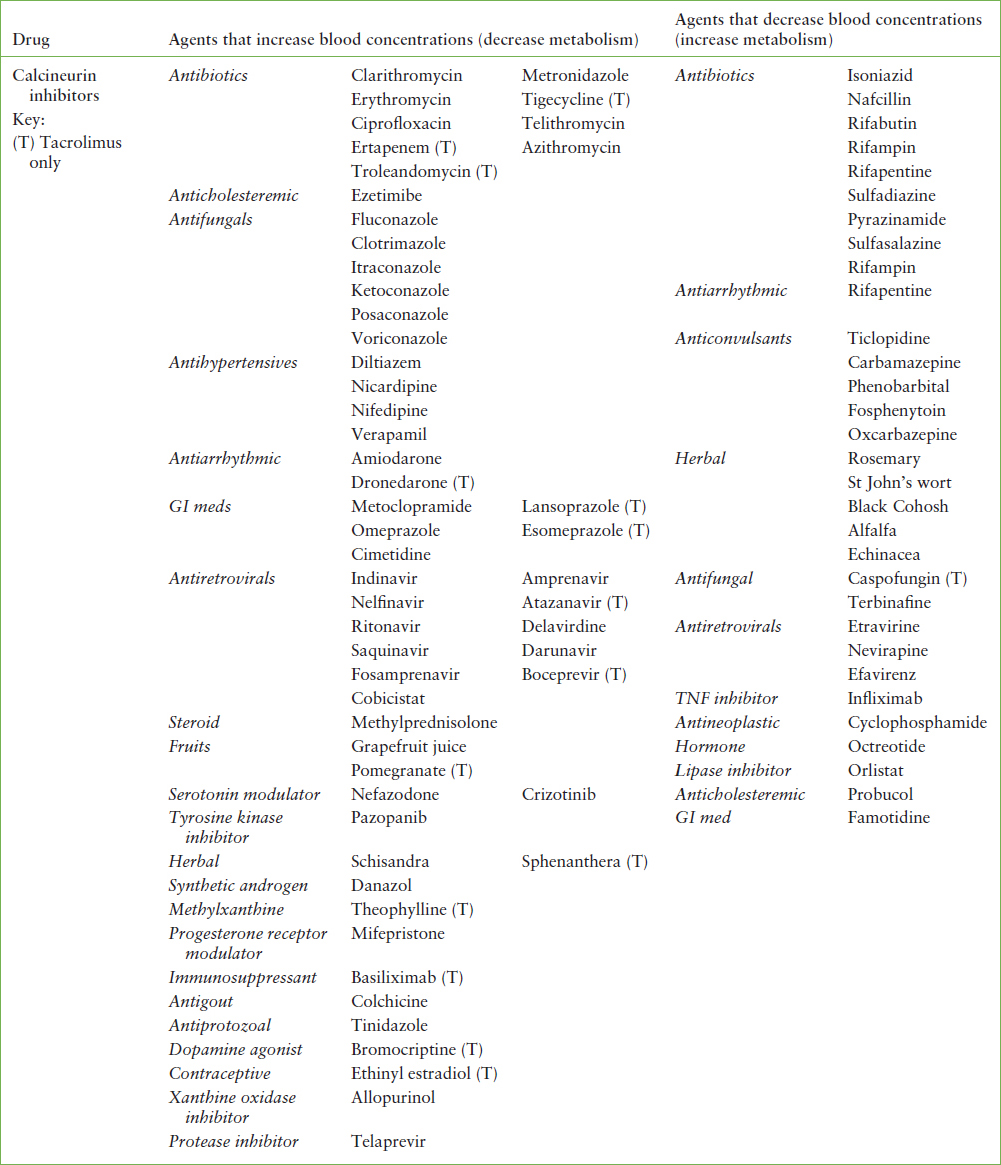

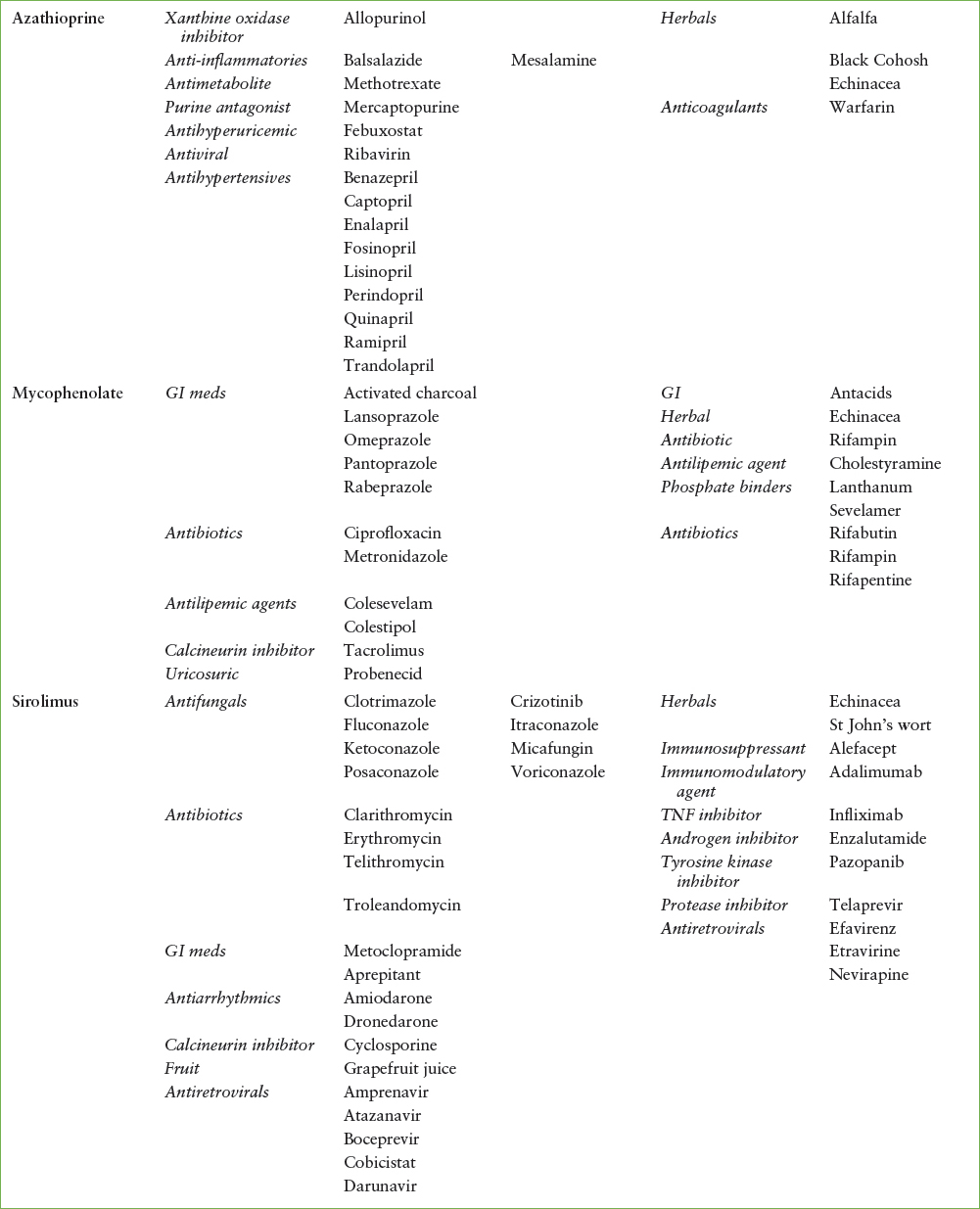

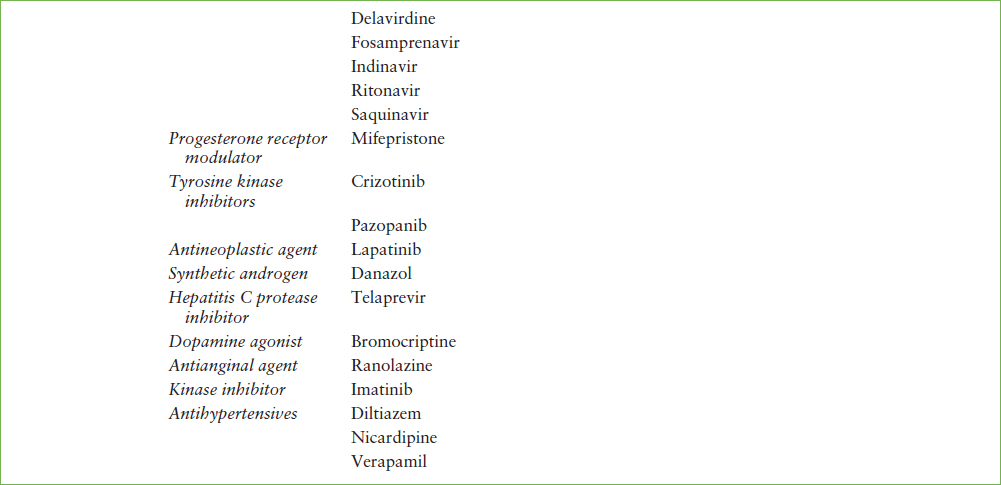

For the majority of uncomplicated infections, the typical course of standard antibiotics should be sufficient. However, many antibiotics interfere with metabolism or excretion of CNIs. A table of common interactions is shown in Table 133.1. The addition of an antibiotic should be cleared first with the treating transplant physician or nurse, as they will likely want to manage follow-up and drug levels while on the additional medication.

The decision to send a patient home or to admit the patient should rely on the usual metrics: appearance on arrival, test results, response to therapy, parental comfort, and availability of follow-up. Patients with high persistent fever, need for continuous intravenous hydration, or an evolving process should remain in hospital until their condition stabilizes. Here again, transplant team input is essential to a successful outcome.

TABLE 133.1

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TRANPLANT IMMUNOSUPPRESENTS AND OTHER COMMONLY USED MEDICATIONS

GRAFT REJECTION

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Clinical signs and symptoms of rejection may be nonspecific and can mimic an infectious illness. They include fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, tachypnea, malaise, and pallor.

• Specific signs and symptoms of cardiac rejection include: tachycardia out of proportion to fever or clinical condition and presence of an S3 (gallop) rhythm. Patients with cardiac rejection are at risk for sudden death.

• Specific signs and symptoms of liver rejection include fever, abdominal pain, and increasing liver aminotransferases.

• Specific signs and symptoms of rejection in pulmonary transplant recipients include hypoxia, tachypnea, and respiratory distress.

• Specific signs and symptoms of rejection in renal transplant recipients include increasing creatinine, fever, and graft tenderness.

• Specific signs and symptoms of rejection in intestinal transplant recipients include increasing stomal output, abdominal pain, and distention.

• If rejection is suspected based on clinical appearance, the transplant team must be notified immediately. Do not wait for laboratory results.

•

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree