Chapter 30 Toxicologic Emergencies

According to the 2009 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System, approximately 2.5 million cases of human exposure to poisons were reported in that year.1 The five substances most frequently involved in all human exposures were analgesics; cosmetics/personal care products; household cleaning substances; sedatives/hypnotics/antipsychotics; and foreign bodies/toys/miscellaneous. The five most common exposures in children ages 5 years and under were cosmetics/personal care products; analgesics; household cleaning substances; foreign bodies/toys/miscellaneous; and topical preparations.1

Exposures can be occupational, environmental, recreational, or therapeutic. Toxic exposures occur through inhalation, ingestion, injection, or contact with skin and mucous membranes. Most poisonings are unintentional, relatively mild, and do not require emergency services. Treatment in a health care facility is required for about 24% of those who contact a poison control center, approximately half of whom are treated and released.1 Only about 16% of these patients are admitted to a critical care unit.1

• Age: The older the patient, the more likely the patient is to die from ingestion.

• Pharmaceuticals: Pharmaceutical agents are generally more toxic than plants, household chemicals, and recreational drugs.

• Polypharmacy: Patients exposed to multiple substances are at increased risk for death.

• Intentional poisonings: Persons who intentionally expose themselves to toxic substances are considerably more likely to sustain adverse events than are those with unintentional exposures.

• Altered mental status or other severe symptoms on presentation: Patients who are significantly compromised upon arrival to the emergency department are more likely to have a poor outcome.

General Priorities for Poisoned Patients

• Administer supplemental oxygen as needed.

• Establish intravenous access and infuse lactated Ringer solution or normal saline solution.

• Give naloxone (Narcan) 0.4 to 2 mg intravenously, endotracheally, intramuscularly, subcutaneously, intraosseously, or sublingually if the patient has a potential opioid exposure.

• Check blood glucose level and infuse dextrose 50% at 50 mL (25 g) intravenously as needed to maintain normoglycemia.

• Administer 50 to 100 mg thiamine intravenously to adult patients with suspected chronic alcohol abuse.

• Initiate continuous cardiac monitoring and obtain 12-lead electrocardiograms as indicated.

• Draw arterial blood gases as indicated.

• Perform serial monitoring of electrolyte levels, vital signs, and respiratory, cardiac, and neurologic status.

• Administer the appropriate antidote (if one is available).

• Provide education to patients, families, and significant others to prevent future incidents.

Identifying the Poison

Toxidromes

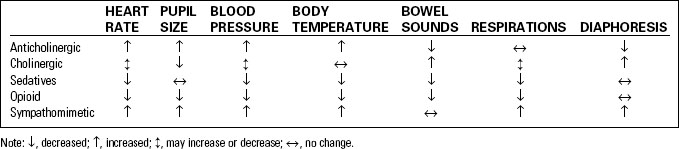

A toxidrome is a set of toxic symptoms caused by a particular class of medication or type of poison. In the patient with an unknown poisoning, early recognition of a toxidrome will enable emergency personnel to rapidly initiate appropriate treatment. Table 30-1 summarizes common toxidromes that can aid in identification of the poison. Table 30-2 lists some other diagnostic clues for identifying unknown toxins.

TABLE 30-2 DIAGNOSTIC CLUES IN UNKNOWN EXPOSURES

| CLUE OR SYMPTOM | POSSIBLE AGENT OR CAUSE |

|---|---|

| Metabolic acidosis | MUDPILES mnemonic: Methanol, Uremia, Diabetic ketoacidosis, Paraldehyde, Isoniazid/Iron, Lactic acidosis, Ethanol/Ethylene glycol, Salicylates/Sympathomimetics |

| Radiopaque medications | CHIPE mnemonic: Chloral hydrate, Heavy metals, Iron, Phenothiazines, Enteric-coated tablets |

| Breath Odors | |

| Alcohol | Ethanol, chloral hydrate, phenols |

| Acetone | Acetone, salicylates, isopropyl alcohol, diabetic ketoacidosis |

| Bitter almond | Cyanide |

| Coal gas | Carbon monoxide |

| Garlic | Arsenic, phosphorus, organophosphates |

| Nonspecific | Consider inhalant abuse |

| Oil of wintergreen | Methylsalicylates |

| Urine Color | |

| Red | Hematuria, hemoglobinuria, myoglobinuria, pyrvinium, phenytoin, phenothiazines, mercury, lead, anthocyanin (food pigment found in beets and blackberries) |

| Brown-black | Hemoglobin pigments, melanin, methyldopa, cascara, rhubarb, methocarbamol |

| Blue or blue-green | Amitriptyline, methylene blue, triamterene, Clorets gum, Pseudomonas |

| Brown or red-brown | Porphyria, urobilinogen, nitrofurantoin, furazolidone, metronidazole, aloe, seaweed |

| Orange | Rifampin, phenazopyridine, sulfasalazine |

Data from Dart, R. D. (Ed.). (2000). The 5-minute toxicology consult. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Anticholinergic Toxidrome

• Includes antihistamines, tricyclic antidepressants, cyclobenzaprine, Parkinson’s disease medications, antispasmodics, mydriatics, and certain plants (e.g., jimsonweed)

• Signs and symptoms include the following:

Cholinergic Toxidrome

• Includes organophosphates and carbamate insecticides, physostigmine, pilocarpine, and nicotine

• Combination of muscarinic and nicotinic effects (Table 30-3)

TABLE 30-3 MUSCARINIC AND NICOTINIC EFFECTS OF CHOLINERGIC TOXIDROMES

| MUSCARINIC EFFECTS (DUMBELS MNEMONIC) | NICOTINIC EFFECTS |

|---|---|

| Diarrhea, diaphoresis | Tachycardia |

| Urination | Hypertension |

| Miosis | Fasciculations |

| Bradycardia, bronchorrhea | Paralysis |

| Emesis | Mydriasis |

| Lacrimation | |

| Salivation |

Therapeutic Interventions for Poisonings and Overdoses

Gastrointestinal Decontamination

Induced Emesis

Although once a mainstay of care, the role of syrup of ipecac in the management of the poisoned patient has significantly decreased in recent years. Routine use of syrup of ipecac is no longer recommended.2 Some of the serious side effects of ipecac include:

• Inducing vomiting may lead to increased intracranial pressure

• Increases risk for hemorrhagic bleeding and profound fluid and electrolyte disorders

Syrup of ipecac is only marginally effective at emptying the stomach, and its use is associated with numerous contraindications and complications. Emesis can delay charcoal administration significantly. However, there are rare circumstances under which ipecac may be considered appropriate,2 and as a result, the drug is still available over the counter and at hospitals throughout the United States.

Activated Charcoal

Recently, some research has indicated that the use of activated charcoal alone is equivalent or even superior to other poisoning treatment modalities and combinations. However, no well-controlled studies have documented significant improvement in patient outcome.3

Given by mouth or gastric tube, activated charcoal has the advantage of being minimally invasive, relatively easy to administer, and safe for both children and adults. Activated charcoal absorbs and binds most commonly ingested substances. Specific contraindications to use of activated charcoal include the following:4

• Ingestion of a corrosive agent or hydrocarbons.

• Decreased or absent bowel sounds (relative contraindication).

• Toxins not bound by charcoal, such as iron, lead, and lithium.

Recommendations for the administration of activated charcoal are as follows:

• In rare cases where syrup of ipecac has been administered, activated charcoal should not be administered until induced emesis has subsided (usually 60 to 90 minutes after the patient last vomited).

• Alert, cooperative patients can drink activated charcoal through a straw.

• Activated charcoal is gritty but not particularly unpleasant tasting. Flavoring (e.g., cherry or chocolate syrup) makes the charcoal more palatable and does not decrease its effectiveness.

• Small, intermittent doses may reduce vomiting.

• Shake the activated charcoal mixture (slurry) thoroughly to eliminate clumping.

• More dilute slurries are easier to drink or pass through a gastric tube, particularly tiny pediatric tubes.

• In patients with an altered mental status, aggressively protect the airway (endotracheal intubation) before administration of activated charcoal. Visualization of the epiglottis is difficult after activated charcoal has been vomited. Aggressive suctioning of aspirated charcoal appears to improve patient outcome.

• A standard-sized Salem sump tube is adequate for activated charcoal instillation.

• Securely anchor gastric tubes to prevent retraction from the stomach to the esophagus.

• Reconfirm appropriate gastric tube placement immediately before administration of activated charcoal.

Multiple-Dose Activated Charcoal

Indications for Multiple-Dose Activated Charcoal5

| Evidence-Based | Frequently Used |

|---|---|

| • Carbamazepine | • Digoxin |

| • Dapsone | • Phenytoin |

| • Phenobarbital | • Salicylates |

| • Quinine | • Sustained-release preparations |

| • Theophylline | • Tricyclic antidepressants |

Gastric Lavage

Gastric lavage may be considered for potentially life-threatening poisonings. Routine use is not recommended, and it should never be performed punitively.6 Gastric lavage may be of benefit in the following situations:

• Symptomatic patients who present within 1 hour of ingestion.

• Symptomatic patients who have ingested an agent that slows gastrointestinal motility.

• Patients who have ingested a sustained-release medication.

• Patients who have taken massive or life-threatening amounts of a substance.

Cathartics

Cathartics—such as magnesium sulfate, magnesium citrate, or sorbitol—have long been added to activated charcoal to enhance gastrointestinal elimination of poisons. However, overuse of cathartics causes diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, increased magnesium levels, electrolyte imbalances, and hypovolemia.7 Cathartics should not be given if bowel sounds are absent. Never administer cathartics to children under 1 year of age; cases of fatal diarrhea have been reported in this population.4

Whole-Bowel Irrigation

Whole-bowel irrigation involves the use of an electrolyte solution (GoLYTELY, CoLyte) administered orally or by gastric tube. Caution must be taken in the pediatric population, and WBI for pediatric patients should be guided by a poison center clinician. WBI produces a rapid catharsis, eliminating most matter from the gastrointestinal tract within a few hours. It most commonly is given following ingestion of an agent that is not well adsorbed by activated charcoal, such as enteric- or sustained-release products, iron, lead, lithium, or zinc. Adverse effects of WBI include nausea, vomiting, and severe cramping as well as increased risk of electrolyte imbalance. It is contraindicated in cases of preexisting gastrointestinal pathology or in patients with increased risk of ileus or obstruction. Swallowed button batteries and cocaine-filled condoms or other packets of illicit drugs can also be removed by WBI.4

Hemodialysis and Charcoal Hemoperfusion

Poisons That Respond to Hemodialysis4,7

| • Acetaminophen | • Paraldehyde |

| • Alcohols | • Phenacetin |

| • Amphetamine | • Phenytoin |

| • Antibiotics | • Potassium |

| • Arsenic | • Quinidine |

| • Chloral hydrate | • Quinine |

| • Ergotamine | • Salicylate |

| • Ethylene glycol | • Strychnine |

| • Isoniazid | • Sulfonamide |

| • Meprobamate | • Theophylline |

| • Methanol | • Valproic acid |

Dialysis is not indicated for the following:

• Ingestion of substances that are highly protein bound

• Agents that are rarely lethal or for which an effective antidote exists

• In patients who are too hemodynamically unstable

• In patients with bleeding disorders

• In patients with poor vascular access

Specific Toxicologic Emergencies

Analgesics

Acetaminophen

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, acetaminophen (Tylenol), a metabolite of phenacetin, and unintentional acetaminophen overdose are consistently the leading cause of acute liver failure in the United States.8 This drug is found in varying quantities in more than 200 miscellaneous remedies for pain, sleep, coughs, and colds.