Chapter 13 Therapeutic approach

Pain can result from overt traumatic incidents or where altered posturomotor control over some time creates repetitive micro trauma, setting the scene for an often trivial incident becoming the ‘tipping point’ for symptom development. When looked for, other associated sub-clinical symptoms have usually also been apparent as part of the dysfunction picture.

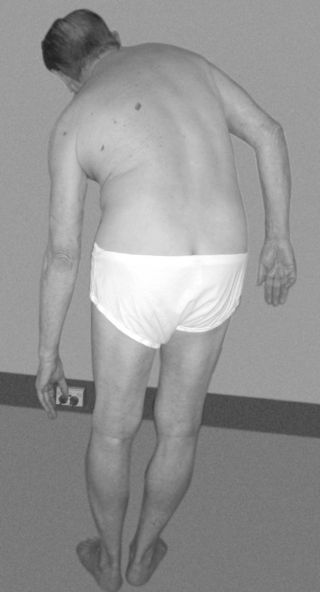

Simply looking at the patient tells us a lot about him. Appreciating the model presented – the salient aspects of normal function (Ch. 6); the common features of dysfunction (Ch. 8); and the clinical patterns (Chs 9 & 10) provides a helpful framework through which to assess the patient. Which joints do we expect to be symptomatic: stiff or overstressed? Knowing what to look for helps decide the test movements and in particular, when passive joint testing, refine the direction of enquiry for possible joint restriction. Assessment confirms or otherwise our predictions and hunches. ‘The model’ hopefully helps the therapist discern ‘the wood from the trees’ and ‘see’ the problem more clearly and find and understand the pain source. Assessment will ideally delineate which are the ‘key elements’ to address, indicate the level of dysfunction and stage of the disorder.

Therapeutic algorithm

Altered control of the spine not only results in various spinal pain syndromes but because it houses much of the nervous system, a plethora of related symptoms seemingly in other organ ‘systems’ or in the head and limbs are possible. The therapeutic approach considered here will principally focus upon ‘spinal pain’ and related proximal girdle disorders with more emphasis on the pelvic girdle. However, it is very important to appreciate that dysfunction in the upper pole of the body also affects function in the lower pole and vice versa, affecting spinal function as a whole. In this respect the upper pole is considered within the therapeutic algorithm and the exercise and movement control approach. Ideal motor function relies on integrated control between the spine, head, both proximal limb girdles and their large ball and socket joints.

The therapeutic algorithm can be distilled into the following main components (summarized in Table 13.1). The irritability of the patient’s condition will dictate how many of the movement tests are performed. The art of the clinician is to gauge the stage of disorder and only test what he/she needs to in order to discern the reason for the patient’s pain. For someone in severe pain, simple observation and gentle manual exploration might be the only measures the patient can comfortably tolerate. As pain settles, more detailed movement testing can ensue. Motor performance will be markedly compromised if the patient has marked pain.

Table 13.1 The therapeutic algorithm: assessment and management

| 1. Assessment |

| A) Observation: |

| B) Movement testing |

• Patterns of active movement in:  Standing: (*=sufficient in more acute presentations where assessment is limited because of irritability) Standing: (*=sufficient in more acute presentations where assessment is limited because of irritability) |

| C) Passive testing/treatment of joints and myofascia with reference to the junctional regions: |

| 2. Therapeutic approach |

Manual: the ‘key’ positive assessment findings become the focus of manual treatment aimed at clearing pain and related symptoms Manual: the ‘key’ positive assessment findings become the focus of manual treatment aimed at clearing pain and related symptoms Therapeutic exercise: should complement manual treatment, be problem specific and redress the general features of dysfunction as described Therapeutic exercise: should complement manual treatment, be problem specific and redress the general features of dysfunction as described |

| It is important to establish fundamental patterns of movement required in ADL activities |

Assessment

The committed and experienced practitioner has learned to understand and see the often subtle nuances inherent in ‘normal’ posturomovement function and the significance of seemingly small differences seen in the dysfunctional state (see Ch. 4). The competent therapist is deft at ferreting out the information needed to help delineate the presenting picture of dysfunction.

Subjective examination

Relevant aspects to explore include the exact area, extent and description of all symptoms; this includes the presence of other pains and symptoms which may not seem related. Is there an apparent reason for their sudden or gradual onset; symptom frequency and whether worsening or stable and the stage of the disorder; symptom irritability and sleep patterns; behavior of symptoms in relation to postures and activities; past history of trauma; occupational posturomovement demands; past and present exercise and leisure activities; previous treatment and demonstration of any exercises prescribed; general health status, medications and results of investigations; patient beliefs as to the source of symptoms; compensable status? Screening for any ‘red flags’ or ‘yellow flags’,32 also begins during the subjective examination.

Objective examination (see Ch. 4)

A) Observation

B) Movement testing (refer to Ch. 4)

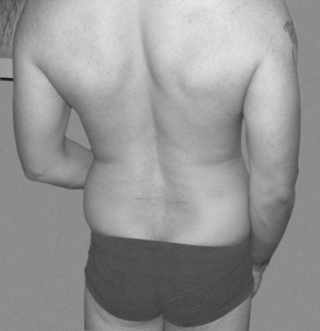

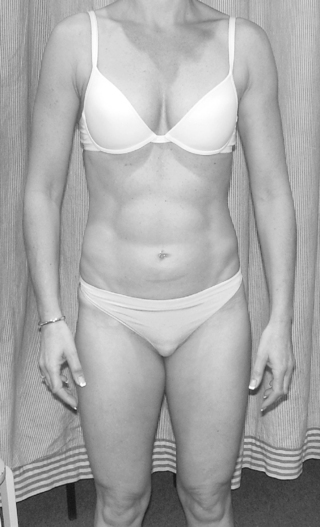

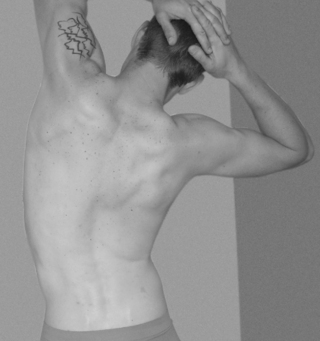

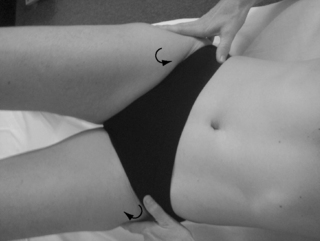

Imbalanced activity between the deep (SLMS) and superficial systemic global muscle system (SGMS) muscle systems is reflected in altered kinematic motion patterns resulting from imbalanced length/tension relationships of muscles contributing to the control of force couples in movement. Examination of patterns of movement begins to indicate the abnormal loading patterns that various joints may have been subjected to. Uneven segmental motion with segmental or regional ‘hinges’ and/or ‘blocks’ may be apparent and symptom producing (Fig. 13.11). Further testing of joint function confirms or otherwise these impressions.

Patterns of active movement

While possible combinations of movement testing are endless and will depend upon the region of pain and stage of disorder, at the initial assessment those which appear to yield the more significant information are mentioned. One is not compelled to perform all those tests listed and clearly in an acute presentation, only a few of the basic tests (marked *) are examined. However, one may need to chase symptoms in say an elite athlete and many if not all may be performed. We are most interested in the ability and quality of the movement patterns the alteration of which can limit or increase range in different regions of the spine and explain symptom development. Altered length/tension relationships in various pelvi-femoral muscles affect pelvic myomechanics and control. Some, none or all of these movements may reproduce the pain or a symptom which is informative however, symptom reproduction is not the primary goal. It is important that the therapist does not over-challenge the patient beyond his abilities as otherwise he will use what he can draw upon and ‘knows’– invariably dominant SGMS activity in predictably provocative kinematic patterns and thus risk exacerbating symptoms. Poor performance of any test indicates avenues for treatment.

Fig 13.12 • This is a better forward bend than most. However, ideally one would like to see better anterior pelvic rotation and co-activation in the abdominal wall (see Fig.13.116).

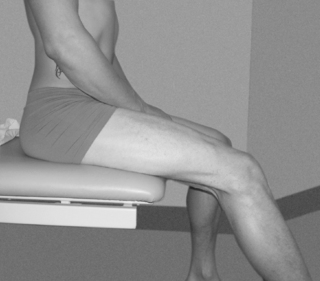

Standing to sitting and return to standing: observing the quality of sagittal weight shift in the pelvis and trunk, axial alignment including head control, lower limb kinematics and the ability to come up to stand without pushing down through the arms (Fig. 13.15).

Fig 13.17 • The same patient as in Fig. 13.16 experiences pain and finds balance difficult. Note the response in the left limbs to aid stability.

In sitting with feet supported:

Fig 13.28 • Poor initiation of sagittal anterior pelvic rotation and forward weight shift in sitting. The patient is 15.

Fig 13.30 • Dysfunctional control of attempted lateral weight shift to the right. Note there is no initiation or shift through the pelvis and instead she tries to ‘pull up’ from above. The bilateral CPC behavior does not allow adaptive weight shift through the torso. See also Fig. 8.26.

Fig 13.31 • When controlled, the pelvis provides stability for active lengthening in the hamstrings.

Fig 13.35 • Manual distraction provided by the therapist helps provide the sensation of the required movement.

The fundamental patterns can be taught from day one in side lying, supine and prone and help reduce local muscle spasm and holding patterns as well as ‘milking’ swollen joints and initiating motor relearning. In the acute scenario, movement is only to just short of any pain, whereas in the subacute or chronic, movement is into stiffness – particularly FPP1 and FPP3. Their establishment is fundamental for properly developing all other functional patterns of pelvic control.

Fig 13.43 • With inadequate support from the LPU the pelvis has subtly rotated in the transverse plane.

Fig 13.47 • When quality in the performance is achieved it can be progressed to stage three with both feet unsupported.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree