Therapeutic Apheresis: Technical Considerations and Indications in Critical Care

Theresa Nester

Michael Linenberger

Technical Rationale and Instruments

Apheresis means to remove. Apheresis instruments are designed to separate whole blood into its component parts in order to selectively remove one component and return the remaining components to the patient. By processing one or more blood volumes, a significant amount of pathologic solutes or cells may be removed while the intravascular compartment remains relatively euvolemic. In an exchange procedure, replacement fluid or blood is given back to the patient in order to allow plasma or red cells to be removed. With any apheresis procedure, some type of anticoagulant is added to the circuit to ensure that blood flows freely.

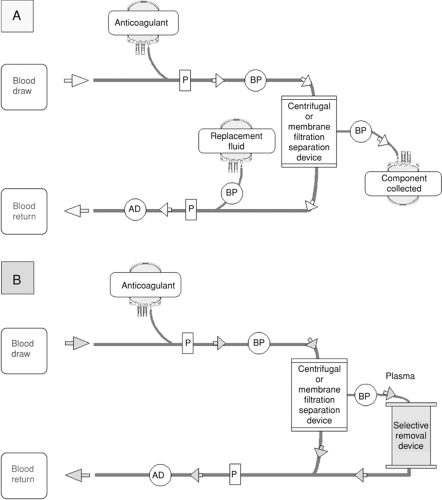

Centrifugation apheresis instruments use either a continuous or a discontinuous flow method to deliver blood to the separation device where blood cells and plasma are differentially sedimented according to their specific gravity. Continuous flow methods draw blood into the extracorporeal circuit, separate blood into components in the centrifugation chamber, divert the unwanted component into a collection bag, and return nonpathologic components to the patient without interruption (Fig. 26-1). Dual venous/catheter access is required for these procedures. Discontinuous, or intermittent, flow methods accomplish the same steps but draw, process, and return a discrete amount of blood extracorporeally before another discrete volume of blood is removed. Discontinuous procedures take a longer time than continuous procedures but require only single vein/catheter access [1, 2].

Some apheresis instruments, predominantly used in Asia and Europe, use a membrane filtration technique to isolate plasma. The extracorporeal membrane consists either of a flat plate or a hollow fiber with a pore size that excludes cellular components from the filtrate. The plasma that is separated in the instrument is diverted for disposal or treatment, while the other blood components are returned to the patient [3].

Specialized columns and instruments have been developed to treat separated plasma, with the goal of selectively removing pathogenic proteins or other solutes. One example is the staphylococcal protein A-silica column, also known as the Prosorba column [4]. This device is Food and Drug Administration-approved for patients with moderate to severe arthritis and immune thrombocytopenic purpura whose disease is refractory to other treatments. Plasma that is isolated by apheresis is passed through the column, where the protein A binds the Fc (fragment, crystallizable) portion of free immunoglobulin-G (IgG) and circulating immune complexes. Because the total amount of IgG removed by the column is relatively small, additional immunomodulatory mechanisms may be responsible for the therapeutic effect with this treatment. Two different columns are approved for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia who have failed combination drug therapy. The heparin extracorporeal LDL precipitation (HELP) system and Liposorber LA-15 system target the removal of low density lipoproteins (LDL) from separated plasma [5, 6]. Additional columns and systems have been tested and used outside the United States. These include a dextran-sulfate column to remove anti-DNA and anticardiolipin antibodies and immobilized polymyxin B or other adsorbers to remove inflammatory cytokines and mediators of sepsis [7, 8 and 9].

Physiologic Principles

The effectiveness of an apheresis procedure in reducing a plasma molecule or cellular component depends on two factors: (a) the distribution of that component between the intravascular and extravascular space; and (b) the rate of regeneration of the component [10,11]. For solutes that move freely between intravascular and extravascular compartments, complete reequilibration between the compartments occurs at approximately 48 hours after a plasma exchange. Circulating blood cells also traffic between sites of vascular margination and/or splenic sequestration and this, in turn, can affect the efficiency of a therapeutic cytapheresis procedure.

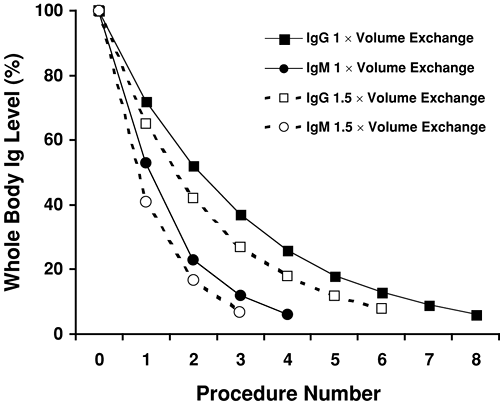

The rate of intravascular regeneration of a pathologic solute or blood cell population after apheresis also depends on the rates of synthesis or production and decay or cell death. Plasma exchange typically removes large molecules at a rate that greatly exceeds their natural synthetic rate, thus a simple one-compartment mathematical model is used to predict the depletion of soluble plasma substances. Assumptions of the model are that the plasma removed is replaced with a fluid devoid of the target substance, and that complete mixing of the replacement fluid with the remaining intravascular plasma volume occurs [10]. Figure 26-2 depicts the kinetics of removal and

regeneration of plasma IgG and IgM after therapeutic plasma exchange. The reliability of the one-compartment model to predict removal of soluble substances may be limited by conditions that cause an expanded plasma volume, such as paraproteinemia, molecules with rapid synthetic rates, and situations where rebound IgG production occurs, such as in the setting of humoral solid organ rejection due to a preformed antibody [12].

regeneration of plasma IgG and IgM after therapeutic plasma exchange. The reliability of the one-compartment model to predict removal of soluble substances may be limited by conditions that cause an expanded plasma volume, such as paraproteinemia, molecules with rapid synthetic rates, and situations where rebound IgG production occurs, such as in the setting of humoral solid organ rejection due to a preformed antibody [12].

The efficiency of cell depletion by cytapheresis is less predictable than soluble substance removal by plasma exchange. Factors that may hinder the prediction include a rapid rate of cell production, such as occurs with untreated acute leukemia, the propensity of the spleen to sequester abnormal circulating cells or platelets, and miscalculation of the plasma volume of the patient. In general, a cytapheresis procedure in which 1.5 to 2.0 blood volumes are processed can be expected to remove approximately 35% to 85% of the target cells [13].

Anticoagulation and Fluid Replacement

Citrate is the most commonly used anticoagulant for plasma exchange and cytapheresis procedures. Heparin is often used with specialized column extraction systems and plasma membrane filtration. Current apheresis instruments limit both the anticoagulant (citrate or heparin) dose and rate of blood return based on the patient’s total blood volume. The operator can also adjust the ratio of anticoagulant to whole blood being processed.

The acid-citrate-dextrose (ACD) solution effectively chelates free or ionized plasma calcium, thereby preventing coagulation of blood and plasma in the apheresis circuit. The precise decrease in ionized calcium in vivo during an apheresis procedure is difficult to predict, as this depends on dilution, metabolism, redistribution, and excretion of infused citrate [14]. Fluid replacement with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or albumin may decrease the ionized calcium further because of citrate in the FFP or calcium binding by albumin. Ionized calcium may typically decrease by 23% to 33%, as measured during donor apheresis procedures [15, 16].

Citrate does not produce an anticoagulant effect in vivo. The half-life in patients with normal renal and hepatic function is approximately 30 minutes. In a patient with severe liver disease, where citrate will not be as quickly metabolized, the operator should reduce the amount and/or rate of ACD used during an exchange. In critically ill patients needing plasma exchange, it is advised that ionized calcium be monitored and intravenous calcium replacement be provided as needed. Some apheresis services use protocols for the infusion of intravenous calcium gluconate or calcium chloride during all therapeutic plasma exchanges [17].

Continuous reinfusion of extracorporeal heparin during an apheresis procedure will affect the patient’s hemostatic parameters. The effect is measurable until the drug is metabolized, usually within 30 to 60 minutes of finishing the procedure. For

patients already therapeutically anticoagulated with heparin, the anticoagulation normally used with apheresis may be reduced or eliminated. The primary providers of critically ill patients must communicate with the apheresis team all information regarding systemic anticoagulation, coagulopathy, and contraindications to anticoagulation, especially when heparin is planned for a therapeutic procedure. It is particularly important to document if the patient has known or suspected heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

patients already therapeutically anticoagulated with heparin, the anticoagulation normally used with apheresis may be reduced or eliminated. The primary providers of critically ill patients must communicate with the apheresis team all information regarding systemic anticoagulation, coagulopathy, and contraindications to anticoagulation, especially when heparin is planned for a therapeutic procedure. It is particularly important to document if the patient has known or suspected heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

Replacement fluid used in plasma exchange may consist of FFP, albumin, or saline. The type of fluid depends on: (a) the patient’s baseline hemostatic parameters, particularly fibrinogen; (b) the anticipated number and frequency of procedures; and (c) the condition being treated. For a patient with a neurologic illness, such as acute Guillain-Barré syndrome, 1 to 1.5 volume exchanges are typically performed every other day with 5% albumin as replacement fluid. This regimen and schedule allows the fibrinogen level to recover between procedures. Alternatively, if a condition requires that plasma exchange be performed daily, some FFP replacement will likely be needed to maintain the patient’s fibrinogen at a hemostatic level. For conditions where a plasma component is felt to be an important part of the therapy, such as with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, FFP should comprise at least half of the replacement fluid [18]. In such cases, fibrinogen and other coagulation factors will not be depleted.

An apheresis instrument that uses a centrifugation technique must deliver a specific volume of packed red cells to the separation chamber in order to maintain the cell/plasma density gradient necessary for efficient selective extraction. The extracorporeal blood volume necessary for this purpose varies according to the specifications of the instrument and disposable tubing kit and the hematocrit of the patient. The American Association of Blood Banks (AABB) recommends that the extracorporeal blood volume (ECV) for a general procedure should not exceed 15% of a patient’s total blood volume [19]. The implications for a therapeutic apheresis procedure can be illustrated by the following example. A 60 kg adult with a hematocrit of 40% has a total blood volume of: 60 kg × 70 mL/kg (the standard conversion factor for an adult male) = 4,200 mL; and a red cell volume of 4,200 mL × 40/100 = 1,680 mL. If the instrument requires 200 mL of extracorporeal red cell volume, then the ECV required to deliver that 200 mL will be 200/1,680 = 0.12, or 12% of the total blood volume. If, however, the same patient has a hematocrit of 20%, the red cell volume will be 4,200 mL × 20/100 = 840 mL; and the required ECV will be 200/840 = 0.24 or 24% of the total blood volume, which exceeds the AABB safety limit. Allogeneic red cells are required when the ECV exceeds 15%. These are either given to the patient as a transfusion prior to the procedure (to increase their pretreatment red cell volume), or used to “prime” the apheresis circuit at the beginning of the procedure (and returned to the patient as part of the return fluid).

Vascular Access

The type of vascular access required for therapeutic apheresis depends on the status of the patient’s peripheral veins, the condition being treated, and the anticipated treatment schedule. The vein or catheter must be able to withstand negative pressures associated with inlet rates ranging from 30 to 150 mL per minute for the draw line, and up to 150 mL per minute for blood being returned to the patient. For a patient needing only one exchange, it may be possible to use antecubital or forearm veins. A 16- to 18-gauge Teflon or silicone-coated steel, back-eye apheresis or dialysis-type needle is required for the draw line. The patient ideally will be able to help squeeze a ball during the exchange.

A large bore central venous catheter is often required for critically ill patients, especially those requiring daily procedures [20]. Temporary or long-term tunneled catheters for adults weighing more than 40 kg should be at least 10 French size. Smaller diameter short-term catheters are acceptable for smaller adults and pediatric patients (Table 26-1). Plastic central venous catheters such as those used for cardiac pressure monitoring are not adequate for the draw line because they collapse under the negative pressure generated from the high inlet flow rate. These catheters or a peripheral vein may be useful as return access under certain circumstances. Peripherally inserted central venous catheter (PICC) lines and port-a-catheters are also not options for venous access. Arteriovenous fistulas created for dialysis access can be used for therapeutic apheresis. The critical care team should consult with the apheresis team prior to placing venous access for the procedure.

Limitations and Potential Adverse Events

When considering therapeutic apheresis, two limitations should be remembered. First, apheresis is not the same as dialysis. It is not usually possible to end a procedure with a large net negative

fluid balance (i.e., greater than 200 to 400 mL) because the deficit is colloid rather than crystalloid, and hypotension is likely to occur. A safe end fluid balance is plus or minus 10% to 15% of the total blood volume. Additionally, it is not recommended that red cells be transfused during the apheresis procedure (other than at the start as a blood “prime”) because the cell separation gradient and cell/plasma interface in the separation chamber may be disturbed. The second limitation is that the procedure is almost always an adjunctive, rather than definitive, therapy for the condition being treated. Thus, while apheresis can be performed on very ill patients, one must carefully consider the risks that are associated with hemodynamic instability, hematologic abnormalities, the need for vascular access, and the priorities for more urgent primary treatments.

fluid balance (i.e., greater than 200 to 400 mL) because the deficit is colloid rather than crystalloid, and hypotension is likely to occur. A safe end fluid balance is plus or minus 10% to 15% of the total blood volume. Additionally, it is not recommended that red cells be transfused during the apheresis procedure (other than at the start as a blood “prime”) because the cell separation gradient and cell/plasma interface in the separation chamber may be disturbed. The second limitation is that the procedure is almost always an adjunctive, rather than definitive, therapy for the condition being treated. Thus, while apheresis can be performed on very ill patients, one must carefully consider the risks that are associated with hemodynamic instability, hematologic abnormalities, the need for vascular access, and the priorities for more urgent primary treatments.

TABLE 26-1. Catheter Recommendations Based on Patient Weight | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Possible adverse complications related to therapeutic apheresis are shown in Table 26-2. Central line complications include procedure-related events, infection, and bleeding [21]. Citrate toxicity occurs in approximately 0.8% to 1.2% of therapeutic procedures [22]. Higher risk is associated with larger process volumes, longer procedure duration, liver failure, alkalosis due to hyperventilation, and use of replacement fluid consisting of blood components that are collected and stored in ACD. Signs and symptoms include a metallic taste in the mouth, muscle or gastrointestinal cramps, perioral numbness, distal paresthesias, and chest tightness. In sedated or unconscious patients, severe citrate toxicity may manifest as tetany, muscle spasm including laryngospasm, a prolonged QTc interval and decreased myocardial contractility [23, 24]. Hypomagnesemia and hypokalemia may also occur as the kidneys increase cation excretion into the urine to facilitate excretion of the citrate load. Although rare, fatal arrhythmias have occurred during therapeutic apheresis [25]. To avoid these complications, ionized calcium should be monitored and intravenous calcium infused, as indicated, either through the return line or as an additive with the albumin replacement fluid.

TABLE 26-2. Possible Adverse Effects of Therapeutic Apheresis | |

|---|---|

|

Hypotension or vasovagal reactions occur in roughly 0.5% to 1% of therapeutic apheresis procedures [24, 26]. Patients with preexisting hemodynamic instability or diminished vascular tone, as seen in certain neurologic disorders, may be at particular risk. In such patients, a net negative end fluid balance must be avoided. Transfusion reactions may occur if blood components are part of the replacement fluid. Allergic reactions have been reported in some patients receiving albumin as the replacement fluid [27].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree