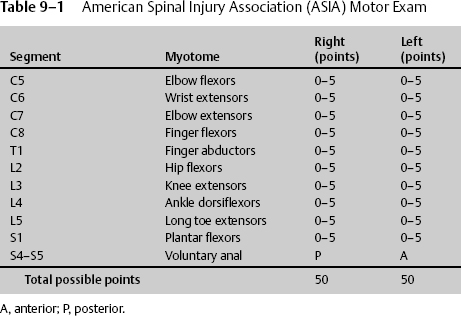

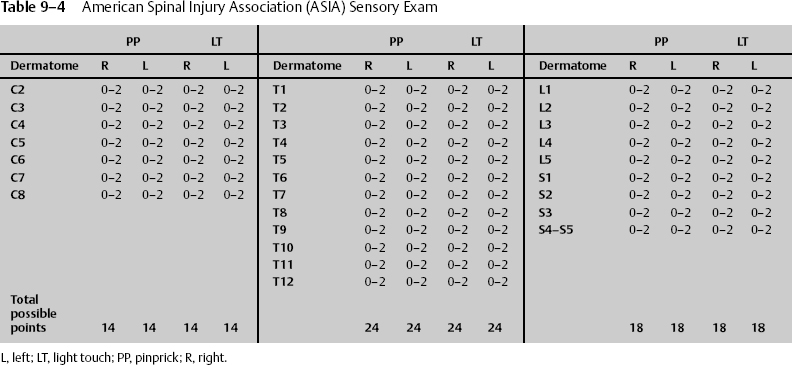

9 Jeffery M. Jones and Dan Miulli Spinal cord (SPC) injuries that occur emergently may be treated surgically based on the initial clinical exam, depending upon whether the deficit is complete or not. When encountering a person with SPC injury, trauma specialists have several considerations, in order of importance: (1) preservation of life, (2) preservation of intact neurologic function, (3) restoration of spinal stability and prevention of spinal deformity, (4) treatment of associated injuries and prevention of complications while optimizing the potential for recovery of neurologic function, and (5) rehabilitation. All patients with head trauma, neurologic deficit, or complaints of neck or back pain must be considered to have a spine injury until proven otherwise. Maintaining a high index of suspicion is the key to prevention of further neurologic injury during transport. Frequently, spinal injuries are missed during trauma resuscitation because attention is focused on more obvious or life-threatening injuries. Particular attention must be given to the unconscious patient or patient who is obtunded from substance abuse who may lack protective muscle tone. When such injuries are merely contemplated, fixation of the head to the fracture board can be achieved by placing wedges under the head and immobilizing the motion of the trunk.1 Immobilization has made a dramatic impact, demonstrating a decline in percentage of complete spinal cord injuries in the United States from 55% in the 1970s to 39% in the 1980s.* When an SPC injury is suspected, the patient must have proper oxygenation, which in many cases can only be achieved with intubation. Tracheal intubation may require fibroscopic control, with insertion of the tube only after topical anesthesia of the airways under titrated intravenous sedation. However, in cases of severe deterioration of vital functions, intubation must be performed without any delay at the site of the accident or in the emergency room. After airway, breathing, and circulation have been stabilized, the trauma team must inspect the patient by log rolling and examining the posterior spine, feeling for step-offs, tenderness, and deformity along the spine. Vitals signs should be monitored frequently to detect any decreased sympathetic tone. A detailed neurologic examination is the most important and sensitive test for spinal cord injury and must be completed at the time of injury and then subsequently every 8 to 24 hours to assess improvement or deterioration in the patient’s neurologic status. The areas of SPC injury include quadriplegia, which is a spinal cord injury from the high cervical to the first thoracic level with complete loss of motor and sensory function below the level of cord injury more than 48 hours after injury, and paraplegia, which is a spinal cord injury below the T1 level involving the thoracic, lumbar, and sacral segments, sparing the upper extremities. The neurologic exam defines the level of the lesion as the most caudal segment with normal motor and/or sensory function. Muscle strength is graded from 0 to 5. C5 motor and sensory quadriplegic patients will have full strength of deltoids and intact pinprick sensation of distal shoulders. The neurologic level is the most caudal segment of the spinal cord with normal sensory and motor function on both sides of the body. The motor level is the lowest key muscle with at least grade 3, provided the key muscles above that level are judged to be normal.1a Once the neurologic exam is completed, the patient can be further classified into complete or incomplete SPC injury, that is, no residual motor or sensory function below the level of the lesion. Signs of incomplete SPC injury are (1) any type of sensation below the level of the lesion (all modes of sensation should be tested), (2) any type of motor function below the level of the lesion, and (3) sacral sparring (perianal sensation, voluntary sphincter, toe flexion). * Data from National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Cener, University of Alabama at Birmingham. The hallmark of the end of spinal shock is the return of the bulbocavernosus reflex (BCR). Spinal shock occurs at the time of injury and usually resolves within a few hours to a few days, sometimes several weeks. It consists of loss of sensation, flaccid paralysis, and absent reflexes below the level of the injury. The mechanism of spinal shock is controversial but may involve deafferentation of motor neurons and interneurons in the gray matter. At the cellular level, it may be as a result of excess potassium accumulating in the extracellular space immediately after trauma and blocking conduction. As stated, the BCR is used to determine the absence of spinal shock. It is the first reflex to return. The absence of this reflex documents continuation of spinal shock or spinal injury at the level of the reflex arc itself.2 It is elicited by genital stimulation and produces anal contraction. No injury may be considered a complete injury until spinal shock has resolved. The treatment for hypotension and bradycardia associated with spinal shock is dopamine, 0.5 to 15 ng/kg/min to desired systolic pressures (max: 20 μg/kg/min). Atropine may also be used for bradycardia (0.5–1.0 mg IV or ET q 3 to 5 min, max: 2 mg).3 To test for the BCR, pinch the glans penis or clitoris, or tug on a Foley catheter and feel for reflexive contraction of the anal sphincter. The presence of the BCR does not suggest the potential recovery of motor or sensory function. Patients with a BCR and no motor or sensory function below the injury (including absent perianal pinprick and deep rectal sensation) have a complete injury with less than a 1% chance of significant motor recovery. The neurologic exam should be measured using universal motor myotomes and sensory dermatomes. For this reason, the standard scale of the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) should be utilized.4 It is important to stress that only a grading of 4 can have a plus or minus associated with it (Tables 9–1 and 9–2). The sensory pinprick is the most important test for determining the location of injury. It should be done using accepted dermatomes, and each side should be given a sensory grade, up to a total of 112 points per side. The perianal pinprick and anal wink test determine if injury is to the bowel/bladder, the conus, and/or the cauda equina. The presence of perianal pinprick sensation suggests incomplete spinal cord injury and may be the only sign of this incompleteness. Pinprick sensation (spinothalamic tract) is more prognostic than posterior column function because of the proximity of the spinothalamic tract to the corticospinal tract in the acute situation; sparing of sensation to pinprick in a motor segment with grade 0 power indicates an 85% chance of motor recovery to at least grade 3 (Tables 9–3 and 9–4). The most important method to determine the validity of the neurologic exam is reflex testing. Patients may not be able to cooperate with the motor or sensory exam, or their cooperation may be limited because of pain or medication. Reflexes will be affected by temperature, paralytics, pain, and secondary gain. However, a change from normal reflexes to hyporeflective or absent reflexes is clinically significant (Table 9–5). Not only the extremities are important for reflex testing. In areas of the spine that do not have corresponding limbs, cutaneous reflexes can often be elicited. These reflexes depend on the thickness of the skin and the ability to perceive small muscle movement in the patient (Table 9–6).

The Spinal Cord–Injured Patient

Immobilization

Immobilization

Neurologic Exam

Neurologic Exam

Level of Lesion

Classification as to Completeness of Spinal Cord Injuries

Spinal Shock

Components of the Neurologic Examination

Components of the Neurologic Examination

| Sensory grading | |

| 0 | No sensation |

| 1 | Abnormal/decreased sensation |

| 2 | Normal sensation |

| Motor grading | |

| 0 | Total paralysis |

| 1 | Palpable or visible contraction |

| 2 | Active movement, gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Active movement against gravity |

| 4 | Active movement against some resistance +/− |

| 5 | Active movement against full resistance |

| NT | Not testable |

| Level | Dermatome |

| C4 | Shoulder |

| C5 | Lateral elbow |

| C6 | Thumb |

| C7 | Middle finger |

| C8 | Little finger |

| T4 | Nipples |

| T6 | Xiphoid |

| T10 | Umbilicus |

| L3 | Just above patella |

| L4 | Medial malleolus |

| L5 | Webbing between great toe and next |

| S1 | Bottom lateral foot |

| S4–S5 | Perianal |

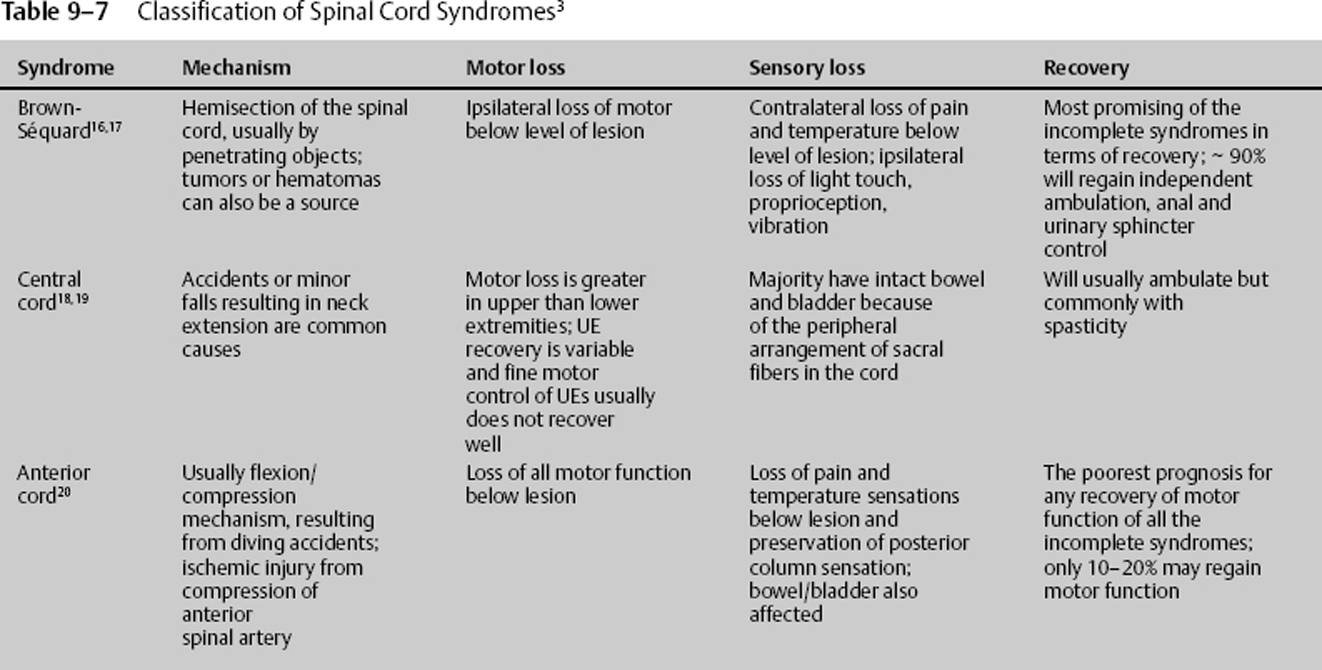

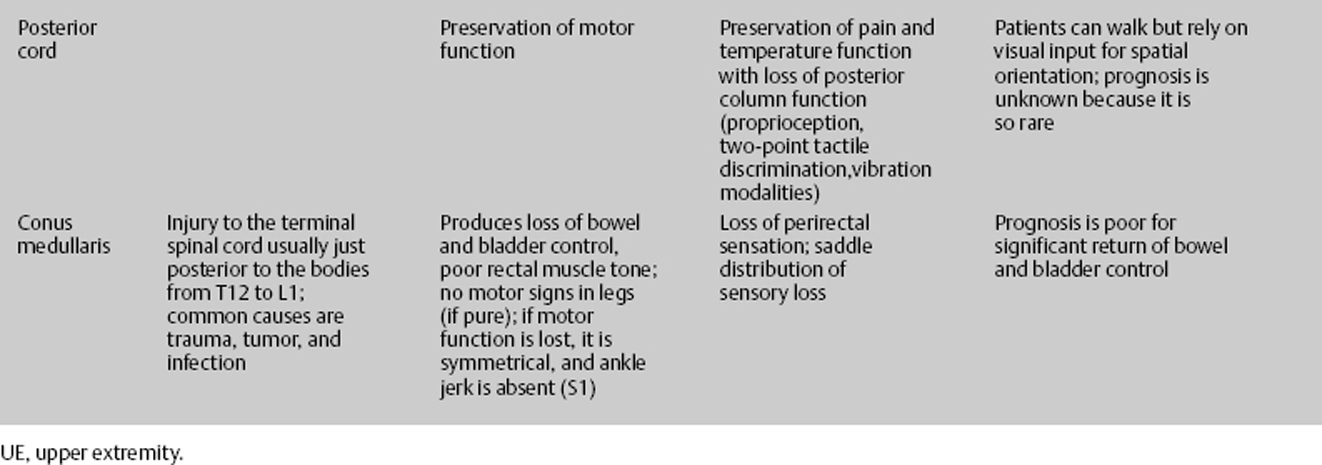

Once a full reflex exam is completed, the patient’s injury can be classified. The classification helps to determine treatment and prognosis (Table 9–7).

In all cases of SPC injury, standard management of acute neurologic injury should be instituted. The patient should have adequate blood flow and blood oxygenation, with intravenous fluids initiated and PO2 maintained at >115 mm Hg to avoid hypotension. Additionally, immobilization should be employed to prevent other injuries, and rehabilitation should be started as soon as feasible.

Indications for Surgery

Indications for Surgery

Absolute indications for emergent surgery:

- Progressing neurologic deficit

- Open (compound) fracture

- Unsuccessful closed reduction of subluxation

Relative indications for early surgery:

- Spinal canal compromise by bone, blood, and so on

- Urinary retention as only symptom

Contraindications for early surgery:

- Medically unstable patient

- Central cord syndrome

| Grade | Reflex quality |

| 0 | No reflex |

| 1 | Hyporeflexia |

| 2 | Normal |

| 3 | Brisk |

| 4 | Hyper-reflexia |

| Reflex | Level | Description |

| Abdominal cutaneous | T8–T12 |

|

| Bulbocavernosus | S2–S4 |

|

| Cremasteric | L1–L2 |

|

| Anal cutaneous | S2–S4 |

|

| Reverse radial | UMN |

|

| Hoffmann’s Priapism | UMN |

|

UMN, upper motor neuron.

Initial Medical Treatment of Spinal Cord Injuries

Initial Medical Treatment of Spinal Cord Injuries

The use of corticosteroids (methylprednisolone [MP]) after acute SPC injury remains controversial. There are many animal models that show efficacy. MP works to stabilize membrane structures and the blood–spinal cord barrier, reducing vasogenic edema; to enhance blood flow in the spinal cord; to inhibit endorphin release; to prevent free radical accumulation; and to moderate the inflammatory response. In a review of the literature, it was found that through 2002, there were 639 studies on corticosteroids and human spinal cord injury, of which 46 studies were of high enough scientific value to be used to develop guidelines for their use.5 The results of these studies are reviewed in Table 9–8.6–21

Methylprednisolone is prepared as 62.5 mg/mL with 30 mg/kg IV bolus over 15 minutes, then 5.4 mg/kg/hr continuous infusion of methylprednisolone for 23 hours started 45 minutes after bolus. It is not for use in life-threatening morbidities, cauda equina syndrome, gunshot wounds, for those under age 13 years, narcotic addiction, complete SPC injuries, or pregnancy.6–21

Rehabilitation

Once the patient has been managed appropriately to prevent any episodes of hypotension and hypoxia, while restoring stability, he or she should progress to rehabilitation. Several classification systems have been used to document SPC injury. Once again, any classification system employed allows health-care providers to track the patient’s progress (Tables 9–9 and 9–10).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

strength of her deltoid, bicep, and brachioradialis; the remaining distal musculature was flaccid. She had pinprick sensation preserved from her lateral elbow up. She had no reflexes, including a bulbocavernosus reflex.

strength of her deltoid, bicep, and brachioradialis; the remaining distal musculature was flaccid. She had pinprick sensation preserved from her lateral elbow up. She had no reflexes, including a bulbocavernosus reflex.