Introduction

A chapter charged with predicting future vulvodynia research necessarily reflects personal opinion rather than fact, in contrast to the other scholarly efforts of this book. The perspective reflected in this chapter is based on my many years of attempting to understand and treat vulvodynia. The chapter is divided into two major sections: first, research avenues to help strengthen the foundation of vulvodynia research are described, and second, specific research ideas are proposed.

The Need for Improved Diagnostic Categories

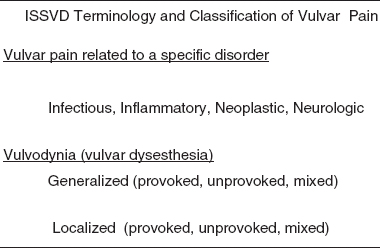

Recognizing the need for an updated vulvodynia classification, the 1999 World Congress of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) convened a discussion group to update the classification of chronic vulvar pain, resulting in the publication of a new classification system [1] (Table 39.1). Chronic vulvar pain refers to vulvar pain lasting more than three months; this category is subdivided into vulvar pain related to a specific disorder (e.g., infectious conditions) and vulvodynia, chronic vulvar pain that exists in the absence of a specific, clinically identifiable disorder.

The category of vulvodynia, in turn, is subdivided according to the pain location (generalized vs. localized) and temporal characteristics (provoked vs. unprovoked vs. mixed) [1]. The ISSVD specifically recommended replacing the term vestibulitis with vestibulodynia, as the former, implying inflammation, was deemed misleading because of the poor demonstrated correlation between vestibular pain and inflammatory indicators. This classification system and associated terminology has met with slow approval. For example, many clinicians continue to use the term vestibulitis and some have questioned whether the divisions truly reflect distinct conditions.

What could explain the slow acceptance of this classification? A useful system should meet at least one of the following goals: (i) it should reflect an understanding of the pathophysiology involved; (ii) it should provide insight into the choice of therapy; or (iii) it should predict prognosis of defined disease subsets. However, the pathophysiology of vulvodynia remains obscure, and therapeutic options have not been well studied for efficacy and prognosis. In addition, a diverse group of providers (e.g., gynecologists, dermatologists, neurologists, etc.), each with their own professional language, manage vulvodynia differently, thereby contributing to various perspectives related to the understanding of the condition and the focus of treatment.

The long-term goal in the treatment of vulvodynia will be the development of a mechanism-based classification system and the practice of making treatment decisions based upon the most effective option against the identified mechanism. Presently, an understanding of the pathophysiology of vulvodynia is uncertain, and such doubt leads to indecision when faced with treatment options. However, in spite of the large number of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) for neuropathic pain, an adequate understanding of any chronic pain condition that might permit a rational selection of treatment based on mechanism has yet to be achieved [2].

The Necessity for More Epidemiological Research

An estimated 7% of women will meet the diagnostic criteria for vulvodynia at some time in their lives, and many will report significant psychosocial problems, including sexual dysfunction, anxiety, depression, and relationship distress [3–6]. Fortunately, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has been involved in research funding for vulvodynia. However, obtaining increased NIH support is unlikely because of limited budgets and competition for other medical priorities; thus, a significant amount of future research funding may arise from the private pharmaceutical sector.

Before such funding can be obtained, however, epidemiologists will need to clearly answer the questions of prevalence, population proportions of vulvodynia subsets, long-term morbidity of chronic vulvar pain, the financial impact of vulvodynia, and, ultimately, the cost/benefit ratio of various treatment options. Although the work of Harlow and Stewart [7, 8] has provided an excellent epidemiologie foundation, far more still needs to be done. For example, information on whether vulvodynia is an orphan disease or just the tip of the iceberg needs to be clarified [8].

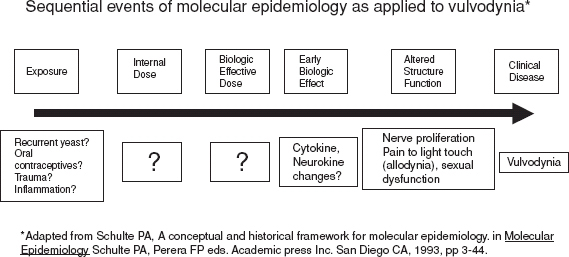

Molecular epidemiology, as a unique discipline within epidemiology, may help in mapping future directions in vulvodynia research. The power of this approach is based upon the identification of molecular markers at the sub-cellular, cellular, tissue, and organism levels [9], which are followed through a mechanistic continuum from exposure to manifestation of clinical disease. An excellent example is illustrated by the exposure to human papillomavirus (HPV) and subsequent development of cervical neoplasia.

Figure 39.1 demonstrates the steps of molecular epidemiology as might be applied to vulvodynia. As is evident, the contemporary understanding of vulvodynia is the equivalent of a “black box”: we have yet to identify agents of exposure and we have yet to fully appreciate the tissue alterations in the presence of disease.

Refining RCT Methods

In the future, RCTs for vulvodynia will require clear and widely accepted definitions of disease, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and outcome measures [10]. Expert panels such as the Initiative on Methods, Measurements, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) group have convened to define what is “success” (i.e., a core outcome domain) [11] and how to measure it (i.e., patient-reported outcome measure) in pain RCTs [12, 13]. The IMMPACT group has focused much of their effort on widely studied chronic pain conditions, such as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) and diabetic neuropathy, but the principles apply to vulvodynia as well.

In vulvodynia outcome studies to date, selected primary outcome variables have fallen into three major categories, each one with strengths and weaknesses: (i) composite pain scores [14, 15]; (ii) individually designed patient- or clinician-reported assessments [16, 17]; and (iii) quantitative sensory testing (QST) [18, 19]. Composite pain score measures consist of one or several psychometric tests combined with other measures of patient- and clinician-reported outcomes. Although the use of reliable and well-validated tools adds important dimensions for analyses, many psychometric measures lack specificity with regards to vulvodynia. Further, scores can potentially be influenced by coexisting pain conditions (e.g., interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel syndrome, etc.). The complexity of composite scores may increase the difficulty of study replication, and subtle variations of method (e.g., order of administration) may influence the outcome. Although individually designed patient- or clinician-reported measures are specific to the condition under investigation, they hold variable degrees of reliability and validity. RCTs using such measures commonly fail to report their associated reliability and validity, thereby weakening the impact of RCT findings.

Figure 39.1 Research methods of molecular epidemiology applied to the question of vulvodynia etiopathogenesis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree