The Eye Examination

Matthew R. Babineau and Leon D. Sanchez

Ocular complaints comprise more than 3% of visits to the emergency department (ED) (1). The severity of these complaints vary from minor to vision threatening, and an emergency practitioner (EP) must be able to risk stratify these to ensure timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment. A thorough and accurate physical examination is therefore an essential skill of all emergency physicians.

ED EVALUATION

History

The history often provides enough information to allow the physician to focus on the appropriate segment of the visual system. Key historical points include age, trauma, current symptoms, ocular history, systemic illness, occupation, and allergies. The patient should be asked if they use corrective lenses (glasses or contact lenses). About 5% of nontraumatic eye complaints are the initial manifestation of systemic illness, so a review of systems should be conducted with special attention to cardiovascular and neurologic symptoms.

Pain and Discomfort

Pathology of the ocular surface or lids usually produces burning, itching, tearing, and foreign body sensation. Orbital or periorbital discomfort is usually described as a dull ache, and may be caused by pathology such as uveitis, episcleritis, scleritis, or acute glaucoma. Peri- or retro-orbital pain may also be due to nonocular causes, such as sinus congestion, vascular or cluster headaches, or intracranial pathology (e.g., aneurysm, arteritis, infection, tumor). It is important to note that, because of sensory overflow from various segments of the fifth cranial nerve, it may be difficult to identify the source of pain by history alone.

Photophobia

Photophobia typically is due to painful contraction of an inflamed iris (as seen in iritis or uveitis), or from inadequate papillary constriction, resulting in excess light reaching the retina. Nonocular causes of photophobia include migraines and inflammation of the meninges (e.g., meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage).

Discharge and Tearing

Discharge is typically a by-product of inflammation of the ocular surface due to allergy or infection. Purulent discharge is suggestive of a bacterial infection. Epiphora (excess tearing) is typically due to emotion, irritation of the ocular surface (due to abrasions, infections, foreign bodies or chemical exposures), or abnormal drainage of tears through the lacrimal system (2).

Redness and Swelling

Redness and swelling of the sclera is most often due to inflammation caused by infections or allergies, though it can rarely be a sign of orbital venous congestion, as can be seen with orbital cellulitis, cavernous venous sinus thrombosis, thyroid ophthalmopathy, and fistulae. Intraocular inflammation will typically cause redness (especially in the perilimbal region), but swelling is rare (endophthalmitis, some cases of scleritis).

Visual Disturbances

Visual disturbances can be a symptom of pathology in the visual system anywhere from the cornea to occipital cortex, and are often related to a nonocular cause. “Blurred vision” may be a catchall term used by patients to describe a number of different visual abnormalities, and the clinician must attempt to specify the exact nature of the disturbance. Glare or halos are caused by light scatter phenomena from unclear ocular media, as in mucinous tear film, corneal edema or epithelial abnormalities, cataract, and/or vitreous haze. Spots or floaters are often due to opacities within the vitreous. Vision loss should be classified as monocular (indicating pathology of the anterior visual pathway and circulation) versus binocular (indicating pathology of the neurovascular system posterior to the optic chiasm).

Diplopia

Diplopia may be caused by serious underlying disease (see Chapter 59). Monocular diplopia is rare and is caused by pathology within the cornea or lens. Binocular diplopia is caused by ocular motility disturbances, such as cranial nerve palsies or extraocular muscle disorders (e.g., entrapment following trauma).

THE OCULAR EXAMINATION

A systemic approach to the ocular examination will facilitate accurate diagnosis and exclusion of vision threatening pathology. The ocular examination can be divided into eight components

1. Visual acuity

2. Face and external eye

3. Extraocular muscles

4. Visual fields

5. Pupils

6. Anterior segments

7. Posterior segments

8. Intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement

VISUAL ACUITY

Visual acuity is the “vital sign of the eye” (3). There are various methods to measure visual acuity. Regardless of the method chosen, it is essential to measure each eye individually, with the other eye completely covered, as patients may look around hands or through fingers. If corrective lenses are available, vision should be tested with these. The acuity of each eye should be documented individually (even if they are the same), and the presence or absence of corrective lenses should be documented as well.

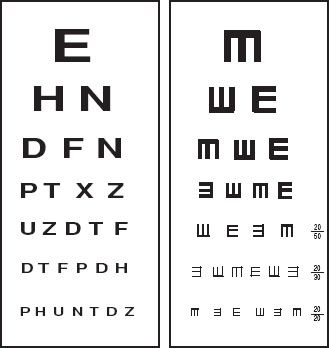

The Snellen chart is the standard tool used to measure visual acuity (3) (eFig. 54.1). The patient is asked to read the smallest line that they can see (4). Visual acuity is expressed as a fraction, where the numerator is the distance of the patient from the chart, and the denominator is the distance at which a patient with normal vision can read the line of letters (2). For example, a visual acuity of 20/50 indicates that a patient can see from 20 feet that which someone with normal vision can read at 50 feet. A “near chart” held at 14 in from patient can replace a Snellen chart for patients who are unable to stand, and the visual acuity is recorded in the same fashion (3). The exception is that near-vision abnormalities can also be due to normal age-related presbyopia, or rarely, traumatic mydriasis (4).

eFIGURE 54.1 Snellen and tumbling E charts. The tumbling E chart can be used to test visual acuity in children or illiterate patients, by asking the patient to indicate which direction the E is “pointing.” (From Weber J RN and Kelley J RN. Health Assessment in Nursing. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

If the visual acuity is not normal, the EP can test the patient using a pinhole card. A pinhole card will correct most refractive errors, so improved vision indicates an optical problem that can be addressed on a nonemergent basis (3). A pinhole card can be easily constructed by punching several holes in the center of a 3- × 5-in index card with an 18-g needle (4). Alternatively, the patient can be asked to view a near chart through the handheld ophthalmoscope, and progressively change the dial until vision is clearest. This will simulate use of corrective lenses (5).

If the patient cannot read the largest letter of the Snellen chart, he should be moved closer to the chart in 5-foot increments, until he can read it. If unable to read the chart at 5 feet, the patient should be asked to count fingers (CF) at 2 feet. If still unable to see, test whether the patient can detect hand motion (HM). If this fails, the patient should be tested for light perception (LP). If they are able to detect light, they should be asked to indicate which direction the light is coming from (this is called “LP with projection”). If there is no light perception (NLP), the patient is considered to be totally blind (6).

If a patient is unable to communicate, or is suspected of factitious blindness or malingering, the practitioner can ensure that the visual pathway is intact by checking for optokinetic nystagmus (4). To perform this test, an object such as newsprint or a tape measure is placed in front of the patient’s eyes, and the patient is asked to fixate on it as it rapidly passes from side to side in front of a patient. If the visual pathway is intact, the EP will note nystagmus-like eye movements which demonstrate that the patient is tracking (4). A variation can be performed using a large mirror held in front of the patient, and slowly moving it to either side of the patient. A patient with intact visual pathway will maintain some degree of eye contact as the mirror moves (4).

Face and External Eye

Obvious abnormalities (trauma, foreign bodies, edema, swelling, erythema) should be noted. The relative positions of the eye within the orbit should be evaluated by gross inspection. Unilateral proptosis may be due to trauma, orbital cellulitis or hemorrhage, cavernous sinus thrombosis, or other causes (6). Bilateral exophthalmos is most often due to hyperthyroidism (2,6). Enophthalmos is often due to an orbital fracture, and may be associated with other findings such as subconjunctival hemorrhage, restriction of upward gaze or hypoesthesia of cheek due to infraorbital nerve injury (2,6). Ex- or enophthalmos may be best appreciated by looking down at the patient’s eyes from above their head (3). Proptosis should be differentiated from keratoconus, where the cornea is cone shaped and may give the illusion of exophthalmos (3).

The EP should note the relative positions of the lids, and the size of the palpebral fissure (the space between the upper lid and lower lid). While ptosis can be present from birth, acquired ptosis is often due to Horner syndrome, isolated CN III palsy, or trauma (2,6). It may also be an early sign of myasthenia gravis. In myasthenia, the EP can attempt to provoke the ptosis by asking the patient to look up for several minutes, to fatigue the palpebral muscles (2). Inability to close the lid may be due to a dysfunction of CN VII (i.e., in Bell palsy).

EXTRAOCULAR MOTILITY

Extraocular motility (EOM) should be tested in the six cardinal directions of gaze (right, left, up and right, up and left, down and left, down and right). It is especially important to assess in cases of trauma, suspected infection, or double vision (3). Each eye should be evaluated separately. Extraocular movements require complex coordination between the brain, cranial nerves III, IV, and VI as well as the four extraocular muscles, so abnormalities of gaze may represent pathology in any of these areas. If no deficits are obvious to the EP, the patient should be asked if they experience diplopia with any movements, and if it is present only when both eyes are open, or only when looking through one eye. Binocular diplopia may be due to orbital infection/tumor/inflammation, nerve compression, or aneurysm in the circle of Willis (3). Monocular diplopia is due to ocular pathology (cornea, iris, lens, or retina) within that individual eye (3).

Nystagmus may be noted during testing of extraocular movements. The two broad types of nystagmus are “jerk nystagmus” (where the eye repetitively drifts slowly in one direction [slow phase], then rapidly returns to normal position [fast phase]) and “pendular nystagmus” (drift occurs slowly and equally in both directions, giving smooth back and forth movement of the eyes) (7). Nystagmus should be described in terms of type (jerk versus pendular), which extraocular motions provoke it (and/or if it is present in primary gaze), the direction of the nystagmus (lateral, vertical, torsional/rotatory), and whether it is extinguishable/fatigable.

Normal individuals may demonstrate a fatigable lateral jerk nystagmus with extremes of gaze (end-point nystagmus), or when fixating on stationary objects while moving (optokinetic nystagmus). Pathologic etiologies of nystagmus are usually due to CNS (thalamic hemorrhage, tumor, stroke, trauma, MS) or toxic/metabolic etiologies (including alcohol, lithium, barbiturates, phenytoin, salicylates, phencyclidine, Wernicke encephalopathy) (7).

VISUAL FIELDS

The visual fields extend in each eye to 170 degrees horizontally, and 130 degrees vertically (2). Testing of the visual fields is an important test of the global visual path from eyes to occipital cortex. A monocular field deficit suggests ocular pathology, while deficits present in both eyes are often due to an intracerebral process. While formal perimetry is the most accurate way to assess visual fields, it is not practical in the ED, so EPs can test visual fields by confrontation field or the Amsler grid.

To perform confrontation field testing, the examiner faces the patient, and asks the patient to close one eye. The examiner closes the ipsilateral eye, and slowly moves a target (typically fingers) into the visual field from a 45-degree angle. The object should be seen more or less simultaneously by the patient and the examiner. After testing in several areas, the process is repeated on the other eye. Any field deficit should be noted and documented (2).

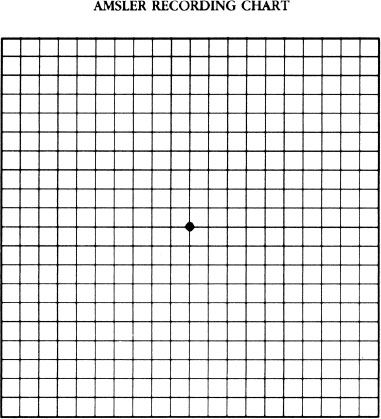

To test the central 10 to 20 degrees of vision (the macula), an Amsler grid is used (eFig. 54.2). Using one eye at a time, the patient is asked to fixate on the central dot, and describe any wavy lines (metamorphopsia) or blind spots (scotoma). Abnormalities of Amsler grid testing typically indicate retinal pathology.

eFIGURE 54.2 Amsler grid. (From Harwood-Nuss A, Wolfson AB, et al. The Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001.)

PUPILS

The clinician should note the size, shape, and symmetry of the pupils. Normal pupils are typically 3 to 5 mm in diameter. Pupillary constriction is mediated by parasympathetic tone, and pupillary dilation is mediated by sympathetic tone. Myriad disease processes, medications, and toxins can cause pupils to be abnormally small (miosis) or large (mydriasis) (Table 54.1). Unequal pupils (anisocoria) are often thought of as pathologic, however, 20% of normal individuals (2,6,8) may have a physiologic difference of 1 mm or less (essential anisocoria). Pathologic anisocoria can be due to Horner syndrome, uveitis, trauma, uncal herniation, CN III palsy, or due to drugs (including nebulized ipatropium) (6).

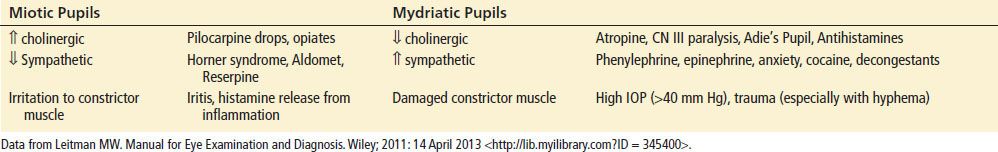

TABLE 54.1

Causes of Miosis and Mydriasis