Chapter 96 The critically ill child

The chapters on paediatric intensive care are intended to help intensivists outside specialised paediatric centres manage common paediatric emergencies. They should be read in conjunction with relevant adult chapters, as there are areas of common interest. Some common neonatal emergencies are also presented.

The major differences between paediatric and adult patients are described below.

PAEDIATRIC INTENSIVE CARE

CARDIORESPIRATORY EVENTS AT BIRTH

During intrauterine life, 60% of blood returning to the right atrium passes directly through the foramen ovale into the left ventricle and ascending aorta. As most of this blood is from the umbilical arteries, the heart and brain are perfused with better-oxygenated blood. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) is high and most of the blood reaching the right ventricle passes through the ductus arteriosus to the descending aorta. Only 10% of right ventricle output passes to the lungs which, although non-functional, require a blood supply for nutrition, growth and development of the lung vasculature.

TRANSITIONAL CIRCULATION

TREATMENT

Many centres successfully employ extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in this situation.

THERMOREGULATION IN THE NEWBORN

Human body temperature is maintained within narrow limits. This is achieved most easily in the thermoneutral zone – the range of ambient temperature within which the metabolic rate is at a minimum. Once ambient temperature is outside the thermoneutral zone, heat production (shivering or non-shivering thermogenesis) or evaporative heat loss processes are required to maintain body temperature within normal limits. Regulatory mechanisms are less effective in the neonate (there is no shivering or sweating), who is otherwise disadvantaged by a high surface area to body weight ratio and lack of subcutaneous tissue.

IMMUNOLOGY OF THE INFANT

The immunological system consists of:

RESUSCITATION OF THE NEWBORN

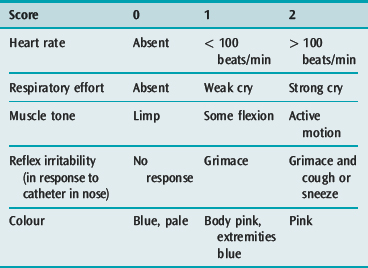

Some newborn infants fail to adapt from fetal to extrauterine life and require immediate cardiopulmonary and cerebral resuscitation. The Apgar scoring system (Table 96.1) scored after 1 minute, remains the most widely accepted method of assessment. The best Apgar score is 10 and the worst is 0. There is an inverse relationship between the Apgar score and the degree of hypoxia and acidosis. It has been suggested that the 5-minute score is a guide to ultimate prognosis but this is questioned. Collection of sequential scores must not delay the institution of resuscitation.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree