The Basics of Survival

John D. Schwartz

Paul J. Vecchio

OBJECTIVES

After reading this section, the reader will be able to:

Know the key elements of basic wilderness survival.

Be able to pack a basic survival kit that is appropriate for your mission needs.

Understand the differences between wilderness survival and survival in a tactical or “SERE” environment.

INTRODUCTION

When laypersons think of survival, they always think of man versus nature, making improvised shelters, finding water, making fires, and foraging for food. Although all of these things are part of survival, it really starts with your mind. Thinking ahead and anticipating the unexpected. Without using your mind and controlling your instincts, a person has no chance at survival.

Survival starts with the preparation for a trip, activity, or mission. Just as a medical practitioner goes through a medical threat assessment prior to deploying to a new operational area, the practitioner should also do a survival threat assessment to assess basic survival requirements for the area. This assessment should consider the possible environments that may be encountered in traveling to or from a location as well as the destination. Assessing the critical elements of survival for these environments can help the practitioner choose which equipment to add to or remove from their basic survival kit.

Most military and many civilian survival courses teach key words like SURVIVAL or STOP to help remember the key elements for survival. In most cases, this is counterproductive, because it focuses the learner on rote memorization rather than learning the important rationale for each key element. When a person understands the rationale for each element of survival, they will be better able to adapt and improvise as the situation demands. Most of survival is learning how to adapt to new conditions and improvise to meet the changing demands.

The Key Elements to Survival

The key elements to survival in their order of importance are: (i) your mind, (ii) first aid, (iii) shelter, (iv) fire, (v) signaling, (vi) water, and (vii) food. In almost all cases, the order of importance will stay the same. In some cases in the desert, fire might switch with water in order of importance, but fire is still high up on the list because deserts get very cold at night.

Your Mind

The first and most important element of survival is getting control of your thought process. This is very easy to say, but in reality is difficult to do. Our natural instincts use fear and panic to initiate a fight or flight response. This is how our ancestors were able to survive encounters with large predators. Today, our fight or flight responses are still very active and many of the drills in military and law enforcement training are intended to redirect and focus these natural instinctive responses. When someone refers to battle-hardened troops, they are referring to their ability to redirect and focus their natural instincts into a coordinated tactical response.

Most incidences that lead to a survival situation also challenge our ability to overcome our initial fear or panic. As a person becomes disoriented or lost, fear and panic slowly begin to take over. This is usually a slow creeping panic. At some point, increased apprehension causes people to start to rush. In most cases, they begin to search for clearings or higher ground. They think, “If only I can see where I am, I will not be lost.” It is during this rushing

state that experienced hunters and hikers will put down their packs or leave their guns propped against trees with the intention of returning once they get their bearings. The result is that without a good reference point (this is what they are looking for) they quickly lose track of where they left their equipment and the situation becomes much worse.

state that experienced hunters and hikers will put down their packs or leave their guns propped against trees with the intention of returning once they get their bearings. The result is that without a good reference point (this is what they are looking for) they quickly lose track of where they left their equipment and the situation becomes much worse.

How does one control these feelings of fear and panic? The British SAS recommends sitting down and making a cup of tea. This is a great response. Sitting down will stop one’s haste, which could lead to loss of equipment, injury, or further anxiety. Making tea forces one to break the chain of thought, which will continue to escalate toward panic. Once this chain of thought is broken and one’s mind can be redirected, the person can later return to the original situation with a controlled and rational thought process. They can size up the situation, observe the environment, and assess their memories of how they came to be in the present situation. Sometimes a person can mentally backtrack and rethink how they got into the situation. The key is to slow down, think, and control fear and panic. Then assess the situation, form a plan, and start to think like a survivor rather than a victim.

First Aid

After having the proper mind set, first aid is the second most important element for survival. Situations like accidents and trauma can also challenge one’s ability to think clearly. Shock or traumatic situations can induce a trancelike state. Victims have difficulty shaking off their initial shock in order to deal with the situation. Even minor injuries can reduce an individual’s ability to function in an appropriate manner. This is where leaders and medical personnel seem to survive better than most people. The recognition of responsibility for others pulls them through more quickly. Medical providers are in many ways the quickest to recover, because of the role they play within the team. Personal health and the health of the team are critical for proper decision making. Because this is a book on tactical medicine, it is assumed the reader has a good understanding of first aid and, therefore, it will not be further discussed.

Shelter

The next key element to survival is shelter. Shelter is critical in almost every situation and environment. In a study of search and recovery (SAR) fatalities, 75% of the victims died within the first 48 hours due to exposure. In cold and wet environments, victims can quickly die from hypothermia without adequate shelter. In desert environments, shelter is essential to protect from the heat during the day and cold during the night. Proper shelter radically reduces water loss in these environments. In tropical environments, shelter is necessary to protect from rain and insects.

Clothing

Shelter starts with clothing. In almost all survival situations, never discard clothing. Try to keep your clothing clean and dry in cold environments. Layer your clothing to produce insulating air spaces. To prevent sweating and overheating, remove layers before climbing or performing strenuous activities. Protect your head and neck, because these are high heat loss areas.

In hot and dry environments, cover up with loose, light-colored clothing to prevent sunburn and minimize thermal absorption. Protect your head with a brimmed hat and your neck with a bandana. Wet your hat and bandana with saltwater, urine, or waste water to take advantage of evaporative cooling. In tropical environments, you should try to carry two sets of clothing. One set is for the daytime; it will be constantly wet and will protect you from thorns and biting insects. Keep the second set of clothing dry for sleeping at night and for protection from nocturnal insects.

Feet

In cold environments, it is always good to have plenty of room to move toes and to allow extra room for socks. Remember: air spaces are what create insulation. Insulated boots can also be very effective in hot dry climates. Temperature on the ground can exceed 65°C (149°F), so insulation in boots can actually reduce the amount of heat absorbed into the body. Boots in tropical environments need to be drainable. Also, pants should tuck into boots to prevent insects and leeches from crawling up your legs.

Eyes

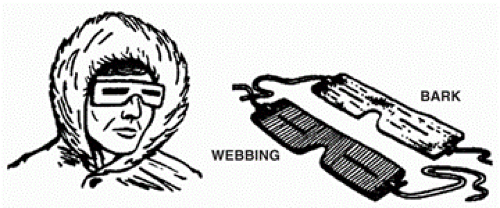

In almost all environments, with the exception of tropical environment, sunglasses or another type of eye protection is needed to prevent eye fatigue and snow blindness. Improvised eye protection can be made by cutting horizontal slits through dark plastic jug material, bark, webbing, or any other appropriate material (see Fig. 9.1).

Choosing a Site for Shelter

The location where a person chooses to construct a shelter will go a long way toward helping them survive adverse conditions. A shelter location should help minimize the effects of cold, wind, rain, sun, insects, and hostile observation. Do not build shelters in exposed windy areas high up on a mountain. Locate shelters to take advantage of the sun in cold climates and the shade in hot dry climates. In a nontactical situation, it is best to place your shelter in a location where rescuers will look for you. If possible, locate near recovery sites. Never place your shelter under dead wood or “widow makers” (dead standing trees). It is always good if you can locate your shelter near a source of drinking water but not too close to stagnant water where insects are more likely to become a problem. Never locate your shelter under a solitary tree that could attract lightening or in a dry river bed that might be prone to flash floods. Avoid locations that are noisy, such as near fast flowing rivers or water falls, because the noise they produce may mask hearing rescuers or hearing pursuers in evasion situations. Also, assess the possibility of other hazards, such as lighting or an avalanche, in choosing a shelter location. Look for your shelter location early so you have time to set up, because once it becomes dark your options are severely limited.

In tactical situations, place your shelter in a location that can provide concealment from hostile observation from both the ground and air. Locate your shelter to provide several camouflaged observation points and escape routes. Minimize the disturbance to the area surrounding your shelter location. The site should be difficult to approach without being clearly seen. Make sure the shelter is small with a low silhouette and is irregularly shaped, because the human eye will pick up on any kind of pattern.

Making an Improvised Shelter

The most common mistake people make in constructing their shelter is making it too large. Smaller shelters are more efficient to build and are more effective at conserving body heat in colder climates. A shelter needs to protect you from rain, wind, snow, or sun. A practical shelter should be easy to build and only large enough to comfortably lie down in. Most survival books show elaborate shelters designed for weeks or months of service. In most cases, the energy expended in their construction is far too high and a small efficient shelter will provide better protection. In a tactical situation, several small irregularly placed shelters are more likely to go unnoticed than a single large shelter.

The kind of shelter one constructs is dependent on the materials available. Shelters can be made from almost all natural vegetation, turf, rocks, and snow, as well as a whole variety of man made materials, such as tarps or plastic sheeting. Natural shelters, such as caves, rocky crevices, fallen trees, or large trees with low-hanging limbs, can provided the framework for simple efficient shelters. Caution should be exercised in evaluating caves and crevices as shelters. In some areas, they may be inhabited by snakes, scorpions, or other stinging insects. Because many caves and rock formations are formed by water, assess the impact of rain on their suitability.

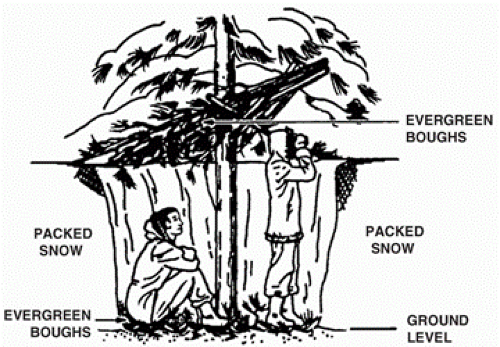

Uprooted logs can make good natural shelters. Piling long sticks over the rooted section of a tree can make the base layer of an effective shelter. Another method is to dig out a small depression parallel to the fallen log and fill the depression with dry leaves or pine needles. Next, lay sticks and vegetation over the top of the log covering the depression. A person is then protected from both above and below. If snow is available, use it to cover the roof vegetation to provide an insulation layer to the shelter. Pulling material into the entrance can further reduce heat loss. Pine trees with low hanging limps can make very good natural shelters. Crawl in under the lower limbs and cut and tie these lower limbs ends higher up in the tree branches. This forms a hollow close to the tree trunk. Rain and snow are naturally funneled away from the center of the tree by the limbs. Vegetation can be piled in the space created next to the tree trunk to form a nest for sleeping. In snowy areas, more snow can be piled on the outer limbs to increase the weather resistance of the central part of the shelter. These kinds of shelters are also effective in tactical situations, because there is little change in the external appearance of the tree (Fig. 9.2).

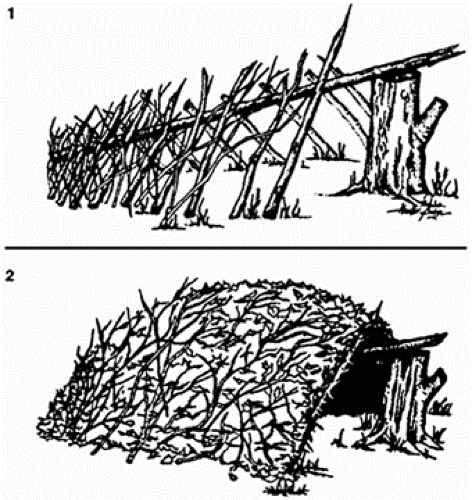

Debris shelters are simple to build and provide weather resistant sleeping areas. Fasten two short poles together and then attach a third long ridgepole to form a V-shaped cave that is long enough and wide enough to accommodate a sleeping area. Continue to pile sticks and vegetation onto the shelter to create a weather resistant barrier. If a tarp or plastic sheeting is available, place this over the first layer

and cover it with more sticks and vegetation to hold it in place. Fill the shelter with leaves or grass to create a nest to hold body heat (Fig. 9.3).

and cover it with more sticks and vegetation to hold it in place. Fill the shelter with leaves or grass to create a nest to hold body heat (Fig. 9.3).

FIGURE 9.2. Pine tree snow shelter. (Courtesy of US Army Survival Manual: FM 21-76 Department of Defense, June 1992.) |

FIGURE 9.3. Debris shelter. (Courtesy of US Army Survival Manual: FM 21-76 Department of Defense, June 1992.) |

Snow is the most abundant insulating material to make shelters. Snow caves can protect survivors from wind and can hold heat for long periods of time. Caution should always be exercised when using an open flame inside any enclosed shelter. Carbon monoxide poisoning kills winter campers every year. Adequate ventilation should always be provided for any flame based heat source.

When the snow forms a crust, in some cases, a snow trench will work to create a shelter. Snow is dug out to create a trench. Pine boughs or blocks of cut snow are placed over the top of the trench to create a roof. Extra snow can then be piled on top to create an insulation barrier. Blocking off the entrance will seal the snow trench from wind and hold the survivors body heat inside.

Shelters in hot, dry climates need to offer protection from the sun in order to reduce water loss. The ground surface in these areas is extremely hot, so the shelter floor should be raised or dug down into the ground to avoid this excessive heat. If there is extra roof material available, layering the roof with an air space between the layers can significantly reduce the temperature within the shelter. Particularly important in desert survival is assessing the amount of effort which will be spent in making a shelter. Water loss is greatly increased with exertion, so simple, easily built shelters need to be considered when water supplies are limited.

Shelters in tropical, wet environments need to protect occupants from rain and insects. Shelters in the jungles need to be constructed above the ground to reduce dampness and the number of insects and snakes that inhabit the area. A water-resistant roof is also necessary to stay semidry.

Fire

The next most important factor affecting survival is fire. Fire provides warmth, light, and will lift your morale as night approaches and the temperature begins to fall. It will also provide a heat source to signal with, dry clothing, purify water, cook food, and keep biting insects at bay. Even in the desert, fire is very important as a nighttime signal and heat source, as nighttime temperatures drop greatly due to thermal radiation radiating back into a clear sky.

The location for a fire should be protected from wind and close enough to provide warmth to your shelter. You should clear the area of vegetation to prevent the fire from spreading. Watch for overhanging trees or deadwood. Keep fires small to keep them under control and to maximize the use of the available fuel supply. Never leave a fire that might jump to nearby vegetation.

Most plant material can be used as fuel with the exception of several poisonous species of wood or vine that can transmit poisonous resin through their smoke. Several examples are: poison wood, poison oak, and poison ivy. Many kinds of animal droppings make excellent fuel. In some areas of the world, local inhabitants burn “cow chips” exclusively for heating and cooking. Peat, when dry, will burn slowly and can be difficult to put out once started. Sometimes coal and charcoal can be found and will produce a very controllable fire. A mixture of oil and gasoline, when placed in a partially filled can of sand, will make an acceptable lamp or cooking stove. In some situations, animal fats can be used to make lamps or small stoves. In heavy snow or swamp conditions, a fire may be built on top of several green logs or on a raised platform to prevent the fire from extinguishing itself in the wet or snowy environment. Many kinds of rubber, plastic, and synthetic cloth will burn and produce thick black smoke that can be used as an effective signal in the desert or in snowy conditions.

Lighting Fires

Matches or lighters are by far the easiest way to make a fire. Keep matches in a waterproof container so that they will function when needed. Water and wind resistant matches are available and will withstand the outdoor environment longer than other common matches, but they are not waterproof as their label says. Small butane lighters will last a long time and are amazingly durable. Even after the butane from these lighters has been used, the spark produced

by the flint can still be used to start fires. A commercially available magnesium rod and flint striker is one of the absolute best backup fire starters available. This device is durable, totally waterproof, and can be used for many fires. One of these should be included in every survival kit.

by the flint can still be used to start fires. A commercially available magnesium rod and flint striker is one of the absolute best backup fire starters available. This device is durable, totally waterproof, and can be used for many fires. One of these should be included in every survival kit.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree