Chapter 28 The anaesthetist and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

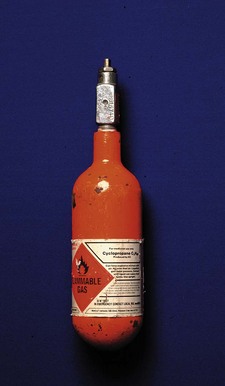

All products, except medicines, used in health care for the diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of illness or handicap are medical devices. There are thus about half a million items falling under the jurisdiction of the MHRA. While some, such as syringes, ventilators and tracheal tubes, are in routine use by anaesthetists, many other medical devices (e.g. artificial eyes, condoms and surgical supports) have little impact on our professional life. Unregulated manufacture and use of medical devices, much like unregulated medical practitioners, have the capacity to inflict great harm, both on patients and on those operating the device (Fig. 28.1).

A glossary of terms used in regulation of medical devices is given in Appendix 1.

Standards

Health-care professionals are by no means the first group to recognize and demand the need for consistent, universal standards in the equipment and materials they work with; in other industries this process dates back many years. An essential requirement for mass distribution of goods is certifiable manufacturing specifications. Industrial standards grew less from a need for safety and more for reasons of commerce, but the potential to advance safe manufacture and use of equipment was soon exploited. During the early industrial revolution, widely used items were custom-built by many manufacturers. The chaos this caused, when trying to put different components together, led to the birth of the standard setting body. The first of these, the British Standards Institute (BSI), began work in 1901 specifying dimensions of rails and steel plate, and now encompasses a wide range of standards from heavy engineering to good employment practice. Attempts at international standardization commenced soon after in the electrotechnical field and culminated ultimately in the establishment of a new body: the International Organization for Standardization based in Geneva, which started work in 1947 (in the spirit of standardization, the abbreviation ISO is retained across all languages). The ISO will be familiar to many anaesthetists as the body that resolved the seemingly random sizes of breathing system connectors (Fig. 28.2) into the universal system we have today (Fig. 28.3).

Figure 28.2 A selection of connectors from older breathing systems showing the lack of uniform dimensions. (Compare with Fig. 28.3.)

These organizations produce the standards, but do not enforce them: in the majority of cases the application of standards is voluntary. Organizations can, however, provide independent inspection of products covered by a standard: a process termed conformity assessment. In the UK, BSI also has a conformity assessment function as well as being a standards body. Where BSI carries out such an assessment and a product meets the appropriate standards, the manufacturer may be entitled to affix the familiar BSI Kitemark to its product as a sign of manufacturing conformity (Fig. 28.4).

Figure 28.4 British conformity assessment: a reproduction of the BSI Kitemark taken from a drain cover.

The ISO has also published generic standards for quality management systems. This is the ISO 9000 family of standards (ISO 9001, ISO 9002, ISO 9003). Manufacturers and many other organizations and businesses may choose, as a marker of quality, to be certified by an independent organization as meeting the requirements of the appropriate ISO 9000 standard. This should not be confused with conformity assessment of the finished product.

CE marking

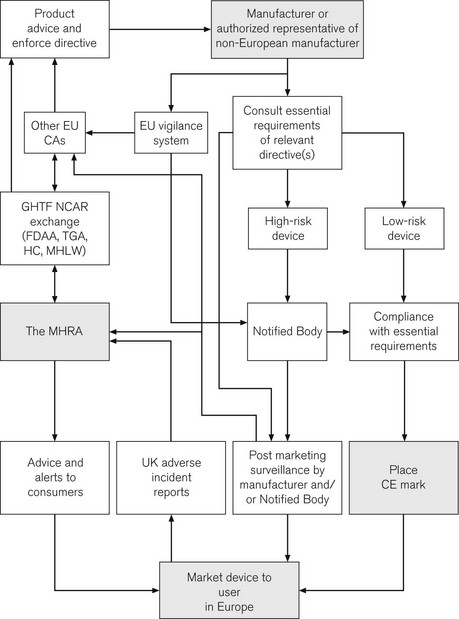

As the EU expands and integrates, there is a need for harmonized conformity assessment of the many goods passing across the borders of member states. Items deemed to require this are described in a number of directives; all medical devices are encompassed within three directives. Within each directive, essential requirements specify the standards for each item. A manufacturer confirms compliance with the essential requirements of a directive by placing the CE (Conformité Européene) mark on their product, once they have followed and complied with an appropriate conformity assessment route (Fig. 28.5). There are certain exceptions from CE marking for ‘custom made’ and investigational devices. Apart from these exceptions, any item specified within a directive cannot be sold within the EU without a CE mark. Regardless of which member state authorizes the manufacturer to place the mark, the item can be marketed in all member states, thus marking achieves both product regulation and compliance with the EC single market. It is inherent in the regulations that products imported from outside the EU are subject to the same set of rules.

Competent authorities and notified bodies

CE marking is of great importance to the health-care sector. Following the incorporation of the Medical Devices Directives, it is now a legal requirement for all medical devices purchased for use in the UK to have a CE mark. A major role for the MHRA is to oversee this process; it is, therefore, termed the Competent Authority for the UK, with other European countries having similar organizations. Exchange of information between Competent Authorities ensures a common approach throughout Europe. Hence, in essence, the MHRA is the UK arm of a large pan-European organization responsible for regulating medical devices. The directives and the standards within are produced by mutual agreement of EU member states, possibly incorporating standards from organizations such as the BSI or ISO (see above). The manufacturer is ultimately responsible for placing the mark and verifying that their product meets essential requirements. For simple low-risk items, the manufacturer can directly place the CE mark. More complex devices, such as pacemakers, require detailed independent verification and certification by an independent organization, termed a Notified Body, who then issue certification to allow the placing of the CE mark. A flow chart illustrates how the system works and where the MHRA may be involved (Fig. 28.6).

The implications of this whole process, for the anaesthetist in particular, and for those involved in producing and modifying medical devices, are discussed in greater detail elsewhere.1 Although recently passed into UK law, it may only be a short time before a CE mark is detectable on every piece of medical equipment in UK hospitals. CE marks are of course not limited to medical devices; other directives stipulate a wide range of marketed products from detonators to jet skis, though not pedalos!