Fig. 19.1

Adolph Erdmann, founder of the Long Island Society of Anesthetists (LISA). (From the Wood Memorial Library-Museum of Anesthesiology, Park Ridge, IL)

Erdmann was not the first to believe that safe and effective administration of anesthetic agents required knowledge of physical science and medicine, careful calculation of drug dosages and techniques of administration, and the development of equipment for airway management and drug delivery. John Snow had made similar observations a half century earlier but had not acted to form a society, because there were few anesthesiologists. Before LISA’s inaugural meeting, Erdmann and his colleagues had concluded that conditions for successful surgery and improved patient outcomes demanded improved education and training of those who administered anesthetics.

There may have been further motivations to form a society. Historians are wedded to context. In 1905, in America, surgeons directed anesthetic administration by diverse personnel, including nurses, medical students, janitors, secretaries, interns, orderlies – and sometimes physicians. Equipment generally consisted of a vaporizer made from a towel, gauze, or a rag [1]. The administrator’s eye, ear, nose, and fingertips served as monitoring devices. The anesthetist performed a task but hardly practiced medicine. Physicians practicing anesthesia might have wished to separate themselves from those less educated, and to establish qualifications for education and practice, but medical education in the US at the turn of the 20th century was unregulated, patchy, and sometimes almost fictitious. The American Medical Association (AMA) had little influence, and primarily existed during its annual meeting. In 1900, with 8,000 members out of approximately 120,000 physicians in the US, the AMA was an annual occasion rather than an institution. Remarkably however, in 1904, it established the Council on Medical Education which initiated the process of assessing medical schools and their curricula, leading to the revolutionary 1910 Flexner Report on medical education [2]. With support from the Carnegie Foundation, and publication nationally, Flexner’s report radically improved medical education.

No doubt, Erdmann and his colleagues dedicated themselves to promoting “the art and science of anesthesia”[3], but we need not accept this statement as explanation in full. A cynic of today, condescending to the past might ask’what art and what science? But there were techniques and tricks and a knowledge of physics and chemistry that could be shared. The same cynic might ask if Erdmann and his colleagues were driven by greed (money) and hunger for power, or unearned status or respectability? The historical record does not overflow with admissions of self-interest. We do know that physicians were modestly paid, their annual income averaging $750 according to AMA surveys [2]. The profession lacked control over the practice of individual physicians, the respective states controlling the profession through licensure and review boards. Whatever interests physicians shared, whatever their competing loyalties, they were, perhaps unconsciously, discovering a new identity. E. P. Thompson, in hisThe Making of the English Working Class, describes the way in which awareness of belonging to a class or group follows the struggle to clarify relationships in terms of values and moral agency:

Class happens when some men, as a result of common experiences (inherited or shared), feel and articulate the identity of their interests as between themselves, and as against other men whose interests are different from (and usually opposed to) theirs [4].

LISA established its identity in the February 1907 issue of theLong Island Medical Journal, with eight articles on anesthesia practices and techniques, as revealed in the Table of Contents:

1.

Spinal Anesthesia

2.

The Techniques of Tubation of the Pharynx to Facilitate Administration of Anesthetics

3.

Major Surgery with Minor Anesthesia

4.

Conditions Governing the Selection of General Anesthesia

5.

Nitrous Oxide and Gas-Ether Sequence for Inducing Anesthesia, with Special Reference to the Bennett Apparatus

6.

The Chloroform and Ether Solution for Anesthesia

7.

Ethyl Chloride and the Newer Anesthetics, Some Personal Experiences

8.

Ethyl Chloride in Oral Surgery

As a final consideration concerning the circumstance of this newly created medical society: US courts had recently shifted in their interpretation of medical malpractice and standards of care. According to Paul Starr,

“physicians came increasingly to rely on each other’s good will for their access to patients and facilities. I have already alluded to the instrumental role of the rise of hospitals and specialization in creating greater interdependence among doctors. Physicians also depended more on their colleagues for defense against malpractice suits, which were increasing in frequency. The courts, in working out the rules of liability for medical malpractice in the late nineteenth century, had set as the standard of care that of the local community where the physician practiced [2].”

Such an argument provided an impetus for defining the practice of medicine, specifically the practice of anesthesia, by standards agreed upon by local practitioners.

A fire destroyed the early records of the society in 1911, the same year that the society changed its name to the New York Society of Anesthetists (NYSA) [1]. The charter of the new society proclaimed its commitment to the “science and art of anesthesia [3].” Erdmann became the first president of the new society and James Gwathmey succeeded him in 1912. In that year, Gwathmey reported that in the US “mortality rates for anesthesia were one death in 5,623 anesthetics, three-fold greater than in the United Kingdom where physician anesthetists by then were on duty in almost all major hospitals [5].” Gwathmey attributed this to the minimal training of US physicians in anesthesia and the use of nurses as anesthesia providers [5].

Other Societies Arose

During the next two decades, a spate of anesthesia societies sprang up in the US: the American Association of Anesthetists (1912), the Interstate Association of Anesthetists (1915), the American Society of Regional Anesthesia (1923), and the International Anesthesia Research Society (1925). These and a multitude of local and regional societies sought to define the education and practices of this developing medical specialty, and to create some certifying system for practitioners [6]. But such fragmentation or “Balkanization of anesthesia into fiefdoms and principalities” delayed agreement on LISA/NYSA’s goals of establishing criteria for qualification as a proficient anesthetist [6].

Physician vs. Nurse Anesthesia

During the 1930s, battle lines were drawn over the relationship between physicians and nurse anesthetists, and whether the NYSA should continue to seek recognition by the AMA. At the same time, a concurrent reality needed to be addressed. Profits were to be made by the administration of anesthetics, and hospitals, surgeons, and nurses competed with physician anesthetists for the rewards. In 1926, the NYSA supported legislation in the New York legislature that would have increased the number of physicians providing anesthesia while limiting the anesthesia practice of others. This unrealistic proposal, which would have created a serious shortage of anesthesia providers, engendered the opposition of surgeons, nurses, and hospital associations. It was not enacted but left bitter feelings against physician anesthetists [7].

As Douglas Bacon wrote:

“Because administration of an anesthetic was a profit center for surgeons and hospitals, physician specialists were struggling. Surgeons could hire a nurse, or other individual, and have that person give the anesthetic. The surgeon charged an anesthetic fee, and the money collected was in excess of the salary paid to the ‘anesthetist.’ Hospitals likewise hired a nurse to give anesthetics and collected a fee that more than paid the nurse’s salary. Finally, general practitioners (GPs) often would refer surgical cases to surgeons who would in turn use the GP as an anesthetist, and by administering the occasional anesthetic the GP increased his/her income [7].”

Multiple forces drove the aspirations of physician anesthetists in the mid-1930s:

1.

Formal recognition of anesthetist’s work as the practice of medicine (which would provide status and financial leverage);

2.

Establishment of quality practice through education, performance standards, examinations, and certification by a recognized American accrediting authority;

3.

Professional independence from the influence of others on clinical decision-making;

4.

Freedom from economic exploitation by surgeons and hospitals.

Certification and Specialty Recognition

In 1930, the NYSA established a committee to revisit the issue of member certification. As I recorded:

“Simultaneously, the Associated Anesthetists of the United States and Canada (AAUSC), under Francis Hoeffer McMechan, recognized the need for a national certification…. As is generally the case with intelligent people who find themselves with a problem, the AAUSC created another committee. As is often the case when intelligent people find themselves in a committee, they failed to agree, leading to another two years of delay and indecision [6].”

During the 1930s, the NYSA began anew, the efforts to achieve specialty recognition from the AMA. That route was unproductive when, in 1912,Gwathmey requested and was refused AMA recognition for a section on anesthesia [7]. By 1935, the Fellowship Committee of the NYSA had established a certification process consisting of oral and written examinations, and a practical demonstration of clinical competence. Physicians from twenty-three states requested applications, but to obtain recognition by the AMA, would require a national organization “in name as well as in fact”. Thus, in February 1936, the NYSA Executive Committee recommended approval of a name change to the American Society of Anesthetists (ASA) [8]. In order to establish some mechanism for awarding fellowship status to qualified physicians, representatives of the ASA, the Surgical Section of the AMA, and the American Regional Society of Anesthetists, met in October 1936 to discuss formation of an American Board of Anesthesia.

In December 1936, the NYSA, having received membership applications from nine other states, officially changed its name to the American Society of Anesthetists by action of its House of Delegates, meeting the AMA’s requirement for a nationwide organization, at least in name. The ASA now had 487 members [9]. They sent John Lundy, head of anesthesia at the Mayo Clinic and a long-time consultant to the AMA, to meet with the Guiding Committee of the AMA and the Advisory Board of Medical Specialties [9]. Although these groups would not agree to a separate Board or Section for anesthesia, a “side-door for entrance into organized medicine” opened.

Erwin Schmidt, Chief of Surgery at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, and a friend of Ralph Waters, proposed an affiliate status for anesthesiologists within the American Board of Surgery (ABS). On January 10, 1937, two representatives of the ASA, Waters and Paul Wood, successfully argued for this proposal before the ABS [10]. In June 1937, the ABS officially recognized the American Board of Anesthesia (ABA). In February 1938, the Advisory Board for Medical Specialties approved this affiliation, thus officially recognizing anesthesia as a medical specialty [3].

While the ASA pursued board status, it concurrently sought recognition as a medical specialty within the family of medicine. In June 1937, in its pursuit of recognition by the AMA through the creation of a Section on Anesthesia, the ASA limited its membership to physicians who were members of the AMA. This removed dentists, scientists, and foreigners from membership [3].

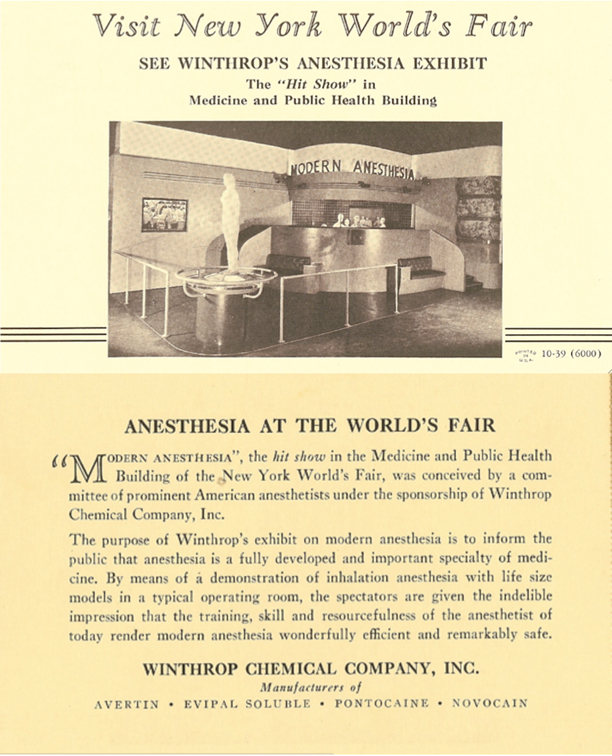

The 1939 World’s Fair in New York provided an opportunity for the ASA, through the Winthrop Corporation, to promote the specialty of anesthesia to the general public (Fig. 19.2). With the theme “The Physician Anesthetist of Tomorrow,” an ambitious display was assembled including a simulated patient and operating theatre. Just how many of the 45 million visitors to the Fair took in the ASA display is unknown’it competed with over 60 foreign government exhibits, 300 priceless works of art from the galleries of Europe, an original copy of the Magna Carta, and an amusement section with a 10,000 seat amphitheatre.

Fig. 19.2

This postcard (front and back) pictured the ASA/Winthrop Corporation’s effort to inform the public, to convince them of the considerable advantages offered by the skills of the anesthesiologist

State associations of anesthesiologists in California, Connecticut, and Indiana had established sections on anesthesia within their state medical societies, and offered educational programs and scientific displays. In May 1939, at the annual AMA meeting in St. Louis, the ASA presented a session on anesthesia, and leaders of the AMA increasingly supported recognition of anesthesia as a specialty [3]. Members of the Council on Scientific Assembly of the AMA, at their meeting in December 1939, recommended establishment of a Section on Anesthesia within the AMA. This recommendation was submitted to the AMA House of Delegates Annual Meeting in June 1940, and was approved unanimously. Anesthesiology was now recognized as a medical specialty by the AMA.

Publication of the ASA Journal, Anesthesiology

The process of legitimizing the specialty also required establishment of organs of communication. First came a monthlyNewsletter, begun in April 1938, which reported items of interest to anesthetists, appointments, meetings, and activities [7]. Next came the journalAnesthesiology, in July 1940. Development ofAnesthesiology had been suspended out of respect for Francis McMechan and his dedication toCurrent Researches in Anesthesia and Analgesia.Anesthesiology commenced publication shortly after McMechan’s death in 1939. It thrived, becoming the pre-eminent journal for anesthesia-related articles.

On February 16, 1941, the ABA gained independent status. The process of organizing anesthetists, developing a corporate identity, defining standards of practice and education, and incorporating these activities within those of other physicians was complete. Anesthesia had arrived as a medical specialty.

World War II Accelerates ASA Growth

The entry of the US into World War II, late in 1941, profoundly changed progress in anesthesia. The expectation of great numbers of casualties and the unfortunate experience of World War I battlefield anesthesia by episodically supervised and diverse anesthetists (corpsmen, nurses, secretaries, and the occasional physician), caused the National Research Foundation to ask eminent anesthesiologists how to manage the anticipated demand. Ralph Waters headed this group of ASA leaders, including Emery Rovenstine, John Lundy, Henry Ruth, Henry Beecher, Paul Wood, Ralph Tovell, and Lewis Booth [10]. They developed an anesthesia training program for physicians that joined the educational and training potential of American anesthesiologists to the emergent demand. Hundreds of physicians received an accelerated program of instruction, at class ‘A’ medical schools with established departments of anesthesia having a chairman who was certified by the ABA. Certain military hospitals handling a large volume of surgical cases with adequate staff were also included, as well as the Mayo Clinic and similar institutions [10].

This program, supported by ASA, contributed to the rapid growth of the specialty after the war. To accommodate the credentialing demands of this new population of partially trained physicians practicing anesthesiology, the Committee on Fellowship of the ASA revived the Fellowship process in 1943, and by 1947, it expanded into the American College of Anesthesiologists. For returning physicians who did not qualify for ABA certification, or who practiced anesthesia part-time, fellowship offered an opportunity to certify skills and knowledge of the practice of anesthesiology [6]. The post-war expansion in the number of residencies and positions indicates the accelerated growth of anesthesiology: in 1940 there were 37 residency programs with108 positions, in 1950 there were 216 residency programs with more than 700 positions [11].

The ASA Changes its Name

In 1945, the total membership of ASA was 1,977. Of those, 739 (37 %) served in the military [3]. As the war drew to a close, the ASA changed its name to the American Society of Anesthesiologists and held the first of its Annual Sessions. Paul Wood, the 1945 first recipient of the ASA Distinguished Service Award, had made the suggestion for a name change the year before, citing correspondence from MJ Seifert of Illinois:

“In 1902, while teaching at the University of Illinois, I coined the word ‘anesthesiology’ and defined it as follows: The science that treats of the means and methods of producing various degrees of insensibility to pain with or without hypnosis. An Anesthetist is a technician and an Anesthesiologist is the scientific authority on anesthesia and anesthetics. I cannot understand why you do not term yourself the American Society of Anesthesiologists?”

Apparently the term anesthesiologist predated the society itself.

A Move to Chicago

In 1946, the ASA celebrated the centenary of the discovery of anesthesia, at its annual meeting in Boston, featuring the Morton Centennial Commemoration and the Ether Centenary celebration. It addressed part of the growing needs of the present and expanding membership, by hiring its first Executive Secretary, John Hunt, who was followed by John Andes in 1960. Need for more space and a more central location within the US prompted the movement of ASA offices to Chicago in 1947. Responding to the maturation of this new specialty, the ASA changed its constitution and bylaws [3]. The new governance structure created component societies at the state or regional level, a Board of Directors, a House of Delegates, and an Executive Committee. This model survives to this day. The House of Delegates first met in St. Louis in 1948. Refresher Courses, instituted at the 1950 Annual Session, continue to be offered today.

The 1940s saw an increase in membership from 538 to 3,393, and by 1960 it had increased to 6,785 [9]. Figure 19.3 indicates three phases of this growth: Slow before World War II: a steeper rise promoted by the war through 1970: and a still steeper increase thereafter, an increase that has yet to abate.

Fig. 19.3

World War II spurred the growth in ASA membership. Growth accelerated further starting at approximately 1970, in part perhaps because of ASA efforts to educate medical students concerning the important role played by anesthesiologists in the care of surgical patients

Founding of the Wood Library-Museum and Other ASA Foundations

In 1949, Paul Wood’s collection of materials related to the history of anesthesia, officially became the Wood Library-Museum (WLM). George Bause admirably tells the development and travels of this unique collection [12]. After being shuffled around New York for three decades, it found a permanent home at the new ASA offices in Park Ridge, Illinois in 1963. It now resides at the enlarged facility built there in 1993. This is the world’s greatest collection of documents, letters, publications, memorabilia, and equipment related to anesthesia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree