THE BLEEDING PATIENT

Most bleeding seen in the ED is a result of trauma—local wounds, lacerations, or other structural lesions—and the majority of traumatic bleeding occurs in patients with normal hemostatic mechanisms.1 In these patients, specific assessment of hemostasis is unnecessary. However, some ED patients have abnormal bleeding due to impaired hemostasis. Identifying these patients requires attention to the history and physical findings.2,3,4 Generally speaking, when patients have spontaneous bleeding from multiple sites, bleeding from untraumatized sites, delayed bleeding several hours after trauma, and bleeding into deep tissues or joints, the possibility of a bleeding disorder should be considered.

Important historical data that aid in identifying a congenital bleeding disorder include the presence of unusual or abnormal bleeding in the patient and other family members and any occurrence of excessive bleeding after dental extractions, surgical procedures, or trauma.5 Many patients with abnormal bleeding have an acquired disorder, such as liver disease, renal disease, or drug use (particularly ethanol, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet drugs, oral anticoagulants, antibiotics, and other salicylate-containing products).2,3,4 Many supplements and herbal preparations, including garlic, ginseng, ginkgo biloba, ginger, and vitamin E, can also increase bleeding tendencies.

The site of bleeding may provide an indication of the hemostatic abnormality. Mucocutaneous bleeding, including petechiae, ecchymoses, epistaxis, GI or GU bleeding, or heavy menstrual bleeding, is characteristic of qualitative or quantitative platelet disorders. Purpura is often associated with thrombocytopenia and commonly indicates a systemic illness. Bleeding into joints and potential spaces, such as between fascial planes and into the retroperitoneum, and delayed bleeding are most commonly associated with coagulation factor deficiencies. Patients who demonstrate both mucocutaneous bleeding and bleeding in deep spaces may have disorders such as disseminated intravascular coagulation, in which both platelet abnormalities and coagulation factor abnormalities are present (see chapters 233, “Acquired Bleeding Disorders,” 234, “Clotting Disorders,” and 235, “Hemophilias and von Willebrand’s Disease”).

Common laboratory tests for hemostasis have their limitations.6,7 They are generally useful and reliable for identifying disorders of coagulation factor function and quantitative platelet availability. However, tests of qualitative platelet function show a significant biologic variation, so that standardization has been difficult to achieve.8,9 In addition, liver disease and renal failure—two conditions that increase the potential for abnormal hemorrhage—may not give rise to consistent and measurable abnormal results on routine tests of hemostasis.10,11,12

THE PATIENT WITH A THROMBUS

Presentation of a patient to the ED with a disorder due to an intravascular thrombosis, such as a deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolus, suggests the potential for an underlying hypercoagulable state (see chapter 234). Premature coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndrome in individuals as young as teenagers have also been linked to hypercoagulable conditions. However, many, if not most, occurrences of intravascular thrombosis are not due to exaggerated hemostasis, but rather are due to local conditions, with blood vessel wall injuries, local inflammation, or vascular stasis provoking the thromboembolic event.13,14

The susceptibility to hypercoagulation may be acquired or genetically transmitted. Common acquired hypercoagulable disorders include essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, antiphospholipid syndrome, and cancer (often occult at the time of acute thrombosis). Inherited hypercoagulable disorders include factor V Leiden, prothrombin mutations, hyperhomocysteinemia, and deficiencies of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin. Patients with inherited hypercoagulable conditions tend to have venous thrombosis, whereas those with acquired disorders can have both arterial and venous clots.

Proteins C and S are vitamin K–dependent antihemostatic factors made in the liver, associated with disorders leading to deficiencies of these proteins inherited in an autosomal manner. Protein C is activated by thrombin and functions with protein S to stop fibrin formation and to stimulate the process of fibrinolysis. Antithrombin is also an antihemostatic protein that blocks activated coagulation factors. Elevated homocysteine level is also a known risk factor for thromboembolism.

Laboratory tests for a hypercoagulable diathesis show wide biologic variation, and standardization among laboratories has been difficult to achieve. The clinical utility of testing patients for suspected hypercoagulable conditions is dependent on the specific disorder.13,14,15

NORMAL COAGULATION

The normal hemostatic system consists of a complex process that limits blood loss through the formation of a platelet plug (primary hemostasis) and the production of cross-linked fibrin (secondary hemostasis), which strengthens the platelet plug. These reactions are counterregulated by the fibrinolytic system, which limits the size of the fibrin clot that is formed and thereby prevents excessive clot formation. Congenital and acquired abnormalities occur in all these systems. The affected patient may have excessive hemorrhage, excessive thrombus formation, or both.

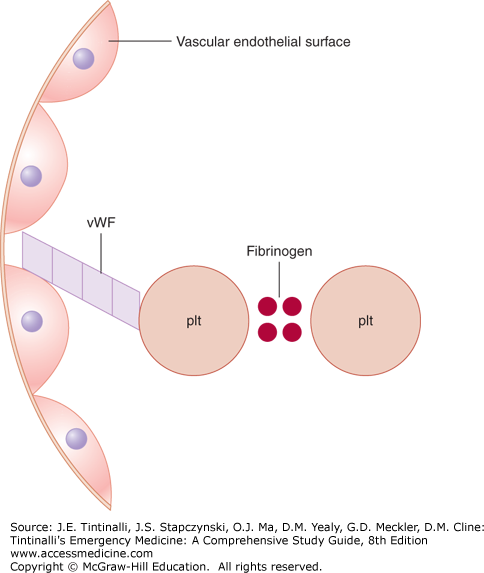

Primary hemostasis is the platelet interaction with the vascular subendothelium that results in the formation of a platelet plug at the site of injury. Required components for this to occur are normal vascular subendothelium (collagen), functional platelets, normal von Willebrand factor (connects the platelet to the endothelium via glycoprotein Ib), and normal fibrinogen (connects the platelets to each other via glycoprotein IIb and IIIa) (Figure 232-1). Primary hemostasis begins within 20 seconds of injury, is short-lived, and requires secondary hemostasis for clot stabilization.

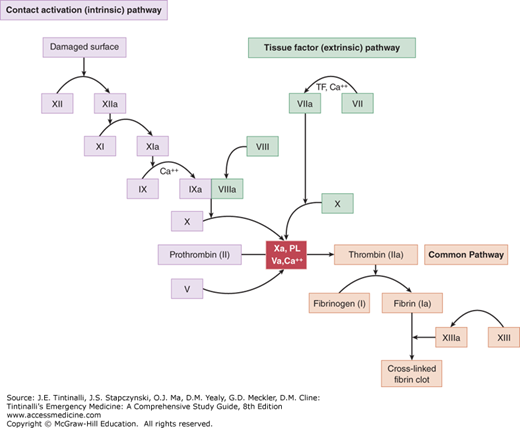

Secondary hemostasis consists of the tightly regulated reactions of the plasma coagulation proteins. The final product is cross-linked fibrin, which is insoluble and strengthens the platelet plug formed in primary hemostasis (Figure 232-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree