Temporomandibular Pain and Dislocation

Darria Long Gillespie

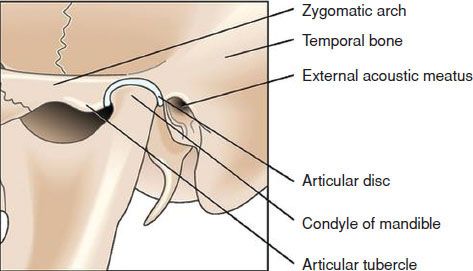

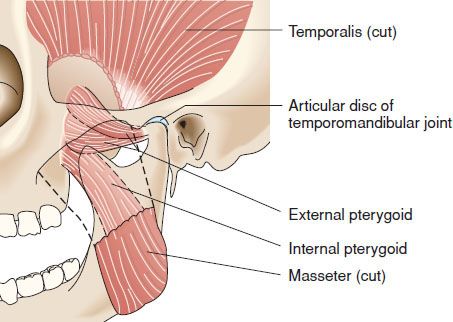

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) consists of the head of the mandibular condyle as well as the articular tubercle and mandibular fossa of the temporal bone (Fig. 64.1) (1). The joint is held loosely by the TMJ capsule, which has a weak surface anteriorly—allowing the variety of movements required, but also the relative ease of dislocation (2,3). The muscles of mastication are divided into two groups: the temporalis, masseter, and internal pterygoid muscles elevate, retract, and close the mandible, while the suprahyoid, infrahyoid, and external pterygoids open and protrude (Fig. 64.2) (4).

FIGURE 64.1 Bony Anatomy. (Adapted from Bickley LS, Szilagyi P. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

FIGURE 64.2 Muscular anatomy. (Adapted from Bickley LS, Szilagyi P. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Temporomandibular Myofascial Pain Dysfunction Syndrome (TMPDS): TMPDS is a neuromuscular disturbance, and its causes are debated. Contributing factors include anatomic abnormalities (congenital or traumatic), microtrauma from clenching/grinding, stress, and systemic arthritides (5,6,7,8). Recent research suggests that sleep bruxism is not a cause of TMPDS (9,10). However, increased clenching and grinding in times of stress contributes to TMPDS and triggers a cycle of muscle pain, dysfunction, and spasm (1,6). Patients who present to the ED are more commonly females in their 20s to 40s (1) and experience unilateral dull pain involving the TMJ, masseter, and temporalis muscles. Pain worsens throughout the day, as well as with chewing, and may refer to the supraorbital, cervical, and occipital regions. Patients may also complain of a “click” or sensation of catching with opening and closing of the jaw (7), although clicking alone without pain is inadequate to make the diagnosis of TMPDS.

The TMJ is vulnerable to all conditions that affect joints in the body, including arthritis, ankylosis, and neoplasm (1). TMPDS secondary to systemic arthritides presents with pain and crepitus in periods of exacerbation and remission. Pain in secondary TMPDS typically is greatest in the morning, presents in younger patients, and has greater severity and joint erosion.

Acute mandibular dislocation: The most common dislocation direction is anterior, in which the condyle is trapped anterior to the articular tubercle due to muscle spasm, prohibiting jaw closure. Posterior, superior, and lateral dislocations are rare and usually associated with severe trauma and other injuries. Dislocations are more commonly bilateral; in unilateral dislocation, the jaw deviates away from the dislocation.

Acute dislocations can be caused by a direct blow to the jaw, seizures or dystonic reactions, and most commonly, due to maximum opening (yawning, laughing, vomiting, dental procedures). Predisposing factors include a shallow fossa and congenital or traumatic weakness of the joint capsule and ligaments (3,11). Patients present with the mouth stretched wide open, are anxious and uncomfortable, and have garbled speech and drooling due to the inability to swallow or move the tongue appropriately. They report exquisite pain due to masseter spasm.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In any patient presenting with facial, jaw, or head pain, the differential diagnosis includes deep space infections (peritonsillar abscess, retropharyngeal abscess, Ludwig angina), odontogenic pain (abscess, caries, tooth fracture), otologic referred pain, zoster, temporal arteritis, trigeminal neuralgia, or parotid gland pathology. Neck and shoulder pain are often reported with TMPDS, and the differential may include other disorders such as referred pain from cardiac ischemia.

Although most cases of TMJ dislocation are clinically obvious, some may be confused with mandibular fracture or acute dystonia. Dislocations and fractures may coexist.

ED EVALUATION

The emergency physician should thoroughly examine the head and neck to evaluate the airway and rule out non-TMJ causes. Examination frequently reveals spasm and tenderness of the masseter externally and internal pterygoid intraorally. The joint itself can be palpated by placing a finger just anterior to the tragus, or in the external auditory meatus and pulling forward on the tragus (Fig. 64.3). Both muscle and joint examinations should be performed while the patient opens and closes the mouth. If this completely reproduces the patient’s pain or demonstrates clicking or crepitus, a TMJ disorder is the likely cause. In severe cases, the jaw deviates toward the affected side, with myofascial spasm and trismus limiting full mouth opening. Examination may show facial asymmetry (12).

FIGURE 64.3 Palpation of the TMJ via pressure on tragus from external auditory canal.